In the summer of 1985, after a hot Minnesota day, a storm knocked out power at the little Carver County Jail in the middle of the night. The sole jailer on duty, 20-year-old Steve Strachan, scalp full of red hair, big key ring on his hip, found himself alone in the dark with 30 inmates.

It was the soon-to-depart Bremerton Police chief’s first job in law enforcement, a part-time, graveyard position to pay the bills while studying at the University of Minnesota. But now, without air-conditioning, without ventilation, the concrete jail on the banks of the Minnesota River was going to turn into a pressure cooker.

“I went through to all the cells and said: ‘This is what I’m going to do, I’m going to make an executive decision,’” said Strachan, now 53. “I was 20 and I didn’t know any better.”

Strachan opened up the cells, and the inmates filed into the jail’s kitchen where they retrieved all the ice cream and popsicles they could carry. Then they all walked down to the riverbank, where they sat in the breeze and ate ice cream.

Strachan told them: “If anybody runs away I am going to be the one who gets in trouble, and we don’t want that, do we?”

After about three hours, as dawn broke, the power returned to the jail and Strachan and the inmates collected their trash and Strachan locked everybody back in their cells.

At about 6 a.m. the chief deputy came into the jail, knowing the power had gone out.

“It was really hot in there,” Strachan told him, “so I opened up all the cells and …”

“Stop,” Strachan recalls the chief saying. “I don’t want to know anymore.”

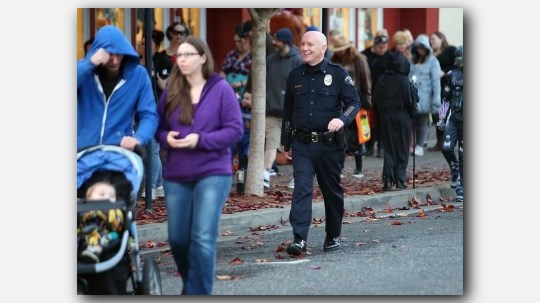

Strachan counts that first job, and that experience, as an important early lesson in human behavior that has informed his career. That career, as a sworn officer, started in 1987 and took him up through the ranks of the Lakeville Police Department, near his hometown of Northfield, Minnesota, through leading the Kent police, the King County Sheriff’s Office and then the Bremerton Police.

“I’ve never had to drag myself to work in 32 years,” he said. “There are challenges, but every single day I’ve liked this job.”

He knew that the older inmates had spread the word around that Strachan was trying to help them, and he knew if there was an escape attempt, other inmates would have run them down.

At the end of the year, when he leaves the department, Strachan plans to take those insights with him as the executive director of the Washington Association of Sheriffs and Police Chiefs, the statewide law enforcement organization.

“This could have gone bad, let’s be honest,” he said. “That’s what is interesting about this job, it’s really about human judgment. It isn’t just about policies and protocols and laws and rules — those are a huge part of it — but it’s trying to read people. It’s going with your gut and trying to solve problems with fellow human beings, and that’s what I took away from that.”

Although Strachan will be working with and for the state’s sheriffs and chiefs, he will be a civilian, something he hasn’t been in 30 years.

“Every day I’ve worn a badge and gun to work,” Strachan said of his upcoming entry into civilian life. “I don’t want to say I’m anxious about it, but I’m getting my arms around it.”

He sees the moment as right for a person who enjoys working across the aisle – something he did during his stint as a Republican in the Minnesota state House of Representatives – and working with people in the community, be them Rotarians or Black Lives Matter activists who held a demonstration in front of the police station.

“I think we are at a moment where people are looking for some common ground,” Strachan said, noting the polarization of discourse over police, where one side thinks police can do no good and the other thinks they can do no wrong. “There’s been lots of discussion about the two polarized sides, but there is an element of 'What’s next? Where do we go with this?'”

Strachan said officers should feel supported by their departments and by their communities – something he says does not always happen – and wants to foster a culture of accountability, where officers can make mistakes and learn from them.

That’s something he points to as his contribution to Bremerton’s department. When officers see other officers out of line, they are encouraged to report it and are commended when they do so. Strachan says that has not only built up morale in the department but built trust with the community.

“The old stereotype of the thin blue line, of cops covering up for each other and hiding malfeasance or hiding bad acts, the longer I’m in this job the more I see just the opposite,” he said. “Our officers hold each other accountable. They expect hard work and ethical work from each other. That’s what a chief is supposed to say, but I see it.”

Some mistakes, though, Strachan has shown he does not tolerate. On Thursday, in one of his more public acts before finishing his tenure, Strachan fired an officer alleged to have punched a restrained man who had spit in her face. He wrote in the notice of discipline other officers had been criminally convicted of such conduct.

“The public expects more from us and they should,” Strachan wrote to former Officer Michelle Griesheimer. The punching incident was reported by a supervisor, who read Griesheimer’s report and said it raised a “red flag” for the use of force.

In his last month, Strachan also had two officers wounded in a fatal shooting with a domestic violence suspect. Officer Kent Mayfield, a 42-year veteran and the more seriously wounded officer, was released from the hospital on Christmas. Strachan wrote in a Kitsap Sun guest column that Mayfield had previously tried to help the deceased suspect, Willie McCord, and that the two officers in the shooting, Mayfield and Officer Allan McComas, expressed sadness when they learned McCord had died.

“The bottom line is that police officers are human beings, we do this job because we want to serve and protect, and no officer wants to use deadly force, ever,” Strachan wrote.

Mayor Patty Lent, who will also leave office at the start of the new year after losing a re-election bid to Councilman Greg Wheeler, hired Strachan in February 2013 and said she would hire him again.

“Oh my gosh, in a minute,” she said.

Lent noted not only the internal changes Strachan made in the department, such as reconfiguring shifts and adding the rank of corporal, but his communication with policymakers as well as residents.

“He is the perfect man for WASPC,” she said, using the acronym for the association.

Strachan plans to continue living in Bremerton with his wife, Sue, and commuting to the Olympia area for work and when the Legislature is in session.

Although he will no longer have arrest powers, and will no longer wear a uniform, he will be working for chiefs and sheriffs.

“I’m not going cold turkey, is another way to say that,” Strachan said.