The Quileute tribe is taking bold action against tsunami and earthquake threats, moving the tribe’s village to higher ground.

The Quileute Tribal School in La Push, like the lower village, sits only 10 to 25 feet above sea level. A major tsunami could reach 100 feet.

“I think it would look like terror coming,” said Superintendent Mark Jacobson, referring to a potential tsunami.

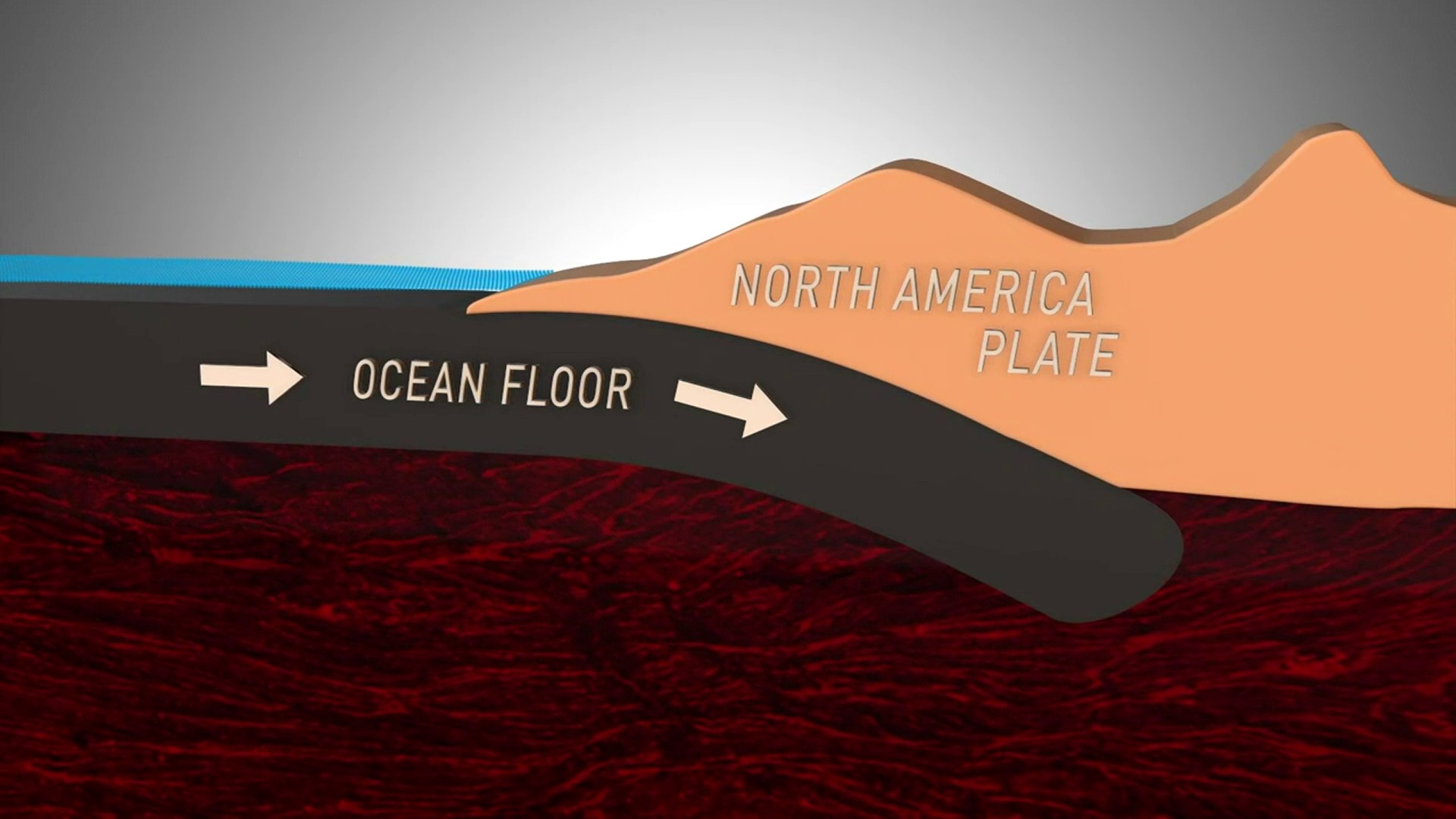

A tsunami could be generated by an earthquake right off the Washington coast or triggered by earthquakes in Alaska or from across the ocean.

“One of these days it could happen here, just like it happened in Japan,” said tribal elder Russ Woodruff, referring to a 2011 earthquake that killed 16,000 in Japan. “That just came quick like that.”

Beginning about three decades ago, as the scientific picture began to emerge on the risks from a Magnitude 9 earthquake, Woodruff and others pushed to get the Quileute tribe ready.

They designed and practiced evacuation drills. The tribe installed one of the first warning sirens on the coast.

But unlike most of us, the Quileute people were here for the last earthquake and tsunami in 1700, and the one before that, and before that.

“I think some of the old legends of some of the old people talking about something, about a big wave. A big, a big wave came in,” Woodruff said.

Moving La Push to higher ground means survival for the Quileute tribe, because they’re going to be prepared for the next earthquake and tsunami.

“There are viable alternatives to just saying, ‘we’re in danger,’” said Larry Burtness, who works for the tribe as a planner and grant writer.

Five years ago a second growth forest was transferred by Congress from the Olympic National Park back to the Quileute tribe. Just weeks ago contractors began cutting trees and pushing a road into a 285-acre area more than 250 feet above sea level.

Eventually, the entire lower village could move up there, along with the people who live there.

“If it were not to take this action, we are putting at risk the future of our tribe,” said Naomi Jacobson, vice chair of the tribal council.

There is always awareness of the past.

“We hear stories about canoes being in trees and people having to run to higher ground and the same types of planning we’re doing now,” she said.

Doing this will take money, and there’s not a lot of money in this economy, which is based mostly on fishing and tourism.

The tribe won a commitment from the Bureau of Indian Affairs last year to fund construction of a 60,000-square foot school. The final cost won’t be known for several months until the design phase is complete.

It’s cost just under $1.1 million so far to plan, clear, and begin the design work funded by both federal and state money.

However, the BIA funding may not cover everything, and that’s just the school. The tribe said it will also launch a capital campaign to lay the groundwork for people to contribute.

The current village could be more focused on tourism with inclusion of vertical evacuation structures and strong concrete buildings where people could run in case of a tsunami.

Think of this as a race with no known finish line. Construction on the new school could begin as soon as spring or summer 2018. Two years after that, the elder center, then the tribal government offices.

Yet, the next quake driven tsunami may not hit for another century or more, or it might strike next week.

What is the price for getting it wrong?

“You wonder when. When it’s going to come here,” Woodruff said. “We’ve just got to stay positive, that we’ve got to get this going and get it up before it does happen.”

Join KING 5’s Disaster Preparedness Facebook group and learn how you and your community can get ready for when disaster strikes.