Washington State is considered second only to California in earthquake vulnerability, but it appears to be the least prepared state or province on the west coast including British Columbia.

This summer, Governor Jay Inslee heard from his subcabinet on earthquakes for his Resilient Washington effort. And there’s a lot to be worried about.

The state Department of Health concluded that roughly 40 percent of the state’s population is compromised in its ability to prepare individually because of disabilities, medical conditions, or poverty.

State guidance updated in 2016 urges people to be prepared for 14 days. That’s two weeks of water, food, warm clothing, and other supplies. In Clallam County, which is vulnerable to tsunamis, landslides, and the loss of bridges and roads, the county guidance is 30 days.

The state leads North America with the only “vertical evacuation” structure in Westport to give people a way to get above a tsunami. However, at least 50 vertical evacuation structures would need to be built to cover other low-lying communities like the Long Beach Peninsula and Ocean Shores.

One of the top recommendations is having an office dedicated to earthquake preparation to speed up the process of getting ready. The governor was told Oregon already has such an office.

“I know what we come to today is not the end of the rodeo,” said Inslee in his opening remarks to the subcabinet. “We’ve got a lot of work to do.”

Currently, the Washington Geological Survey, which is part of the Department of Natural Resources, is asking again for money to complete the mapping of areas vulnerable to tsunami inundation. It’s just 50 percent complete. Only five of the state’s 39 counties has had even a basic seismic assessment for schools.

The request failed to pass last year’s budget.

The current plan is to ask for about $500,000 to complete the tsunami study and $1.2 million to complete the school assessment.

Much of what was discussed involved buildings, particularly older buildings referred to as unreinforced masonry structures (URMs), which are made largely of brick and concrete block and generally built before World War II.

In the 6.8 Nisqually earthquake, which was centered near Olympia in 2001, much of the damage was to URMs in both Olympia and Seattle. Scientists say Tacoma was largely spared damage because the city sits on ground that tends to not magnify the effects of shaking.

California currently requires such structures be retrofitted to withstand the shaking of earthquakes. The governor was told such retrofits in Washington state are at the behest of city codes and generally only required if the building is going to be substantially remodeled.

Retrofits are often easy to spot, with the addition of angled steel bracing and plates seen bolted along the walls at floor levels to keep those floors better tied to the walls.

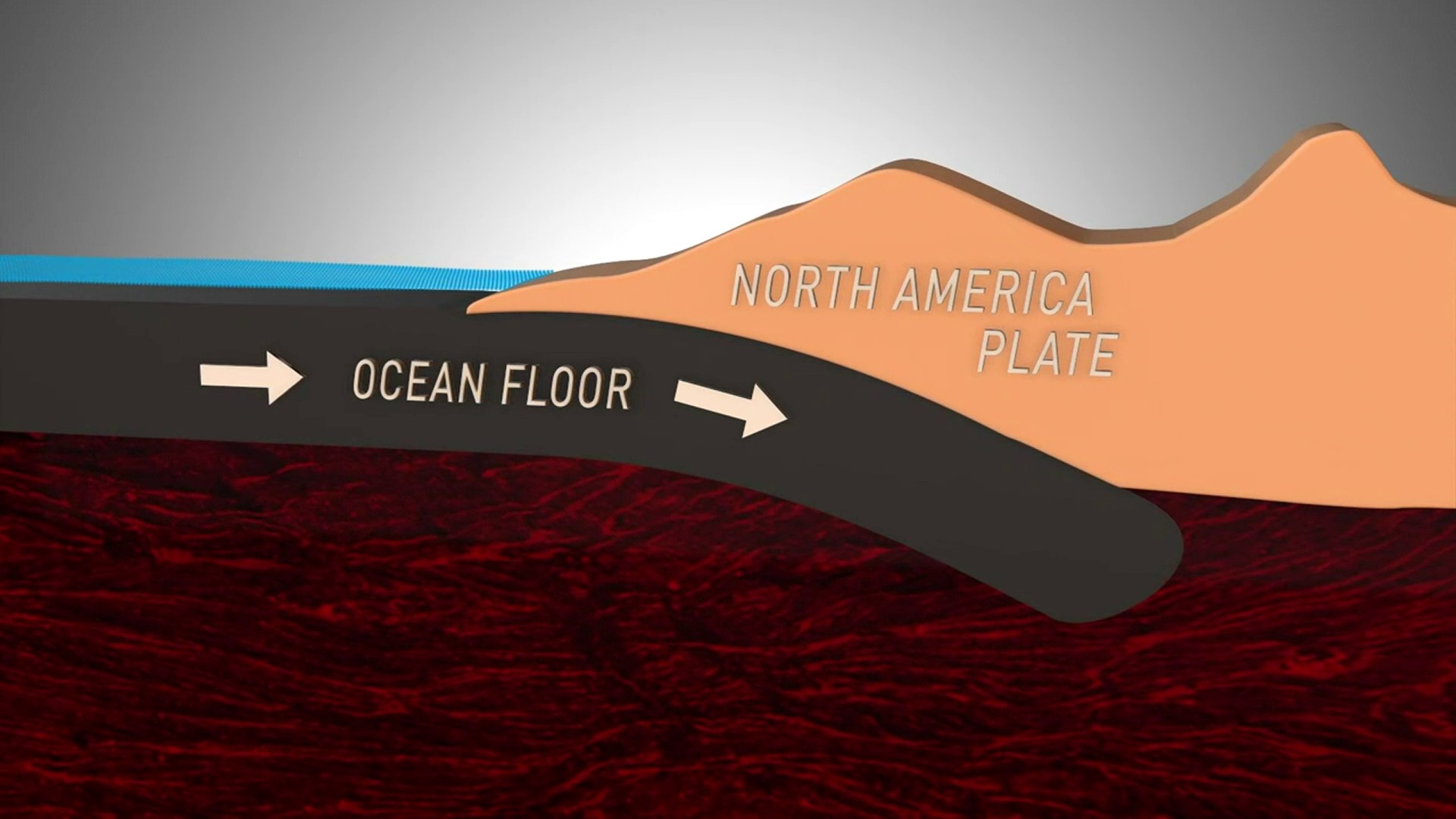

A key difference between California and Washington is that California experiences serious quakes more often than Washington. However, a much stronger magnitude 9 coastal earthquake along the Washington coast would also come with tsunami waves and be much like the 2011 Tohoku quake and tsunami that killed 16,000 people in northeastern Japan.

“California really started off after the 1933 Long Beach earthquake,” Maximillian Dixon, earthquake program manager for Washington’s Emergency Management Division, told the Governor.

Other questions involve building a better communications system for first responders, creating an earthquake insurance authority program, better protecting the state’s drinking water supply, establishing lifeline routes along major corridors such as Interstate 5, 405, and 90, and spending $195 million to continue retrofitting 400 bridges.

All of it will cost money and take decades to plan and manage. Emergency Management says since the late September meeting more and more legislators are being briefed.

Join KING 5’s Disaster Preparedness Facebook group and learn how you and your community can get ready for when disaster strikes.