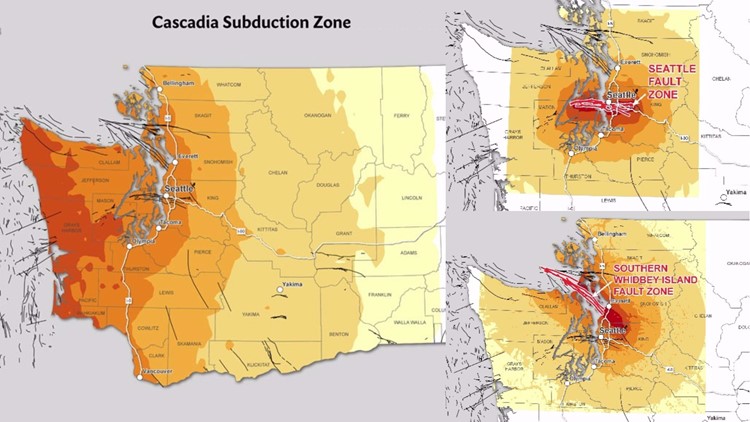

The western half of Washington state is considered earthquake country, with the potential for very large quakes.

Scientists have their top three.

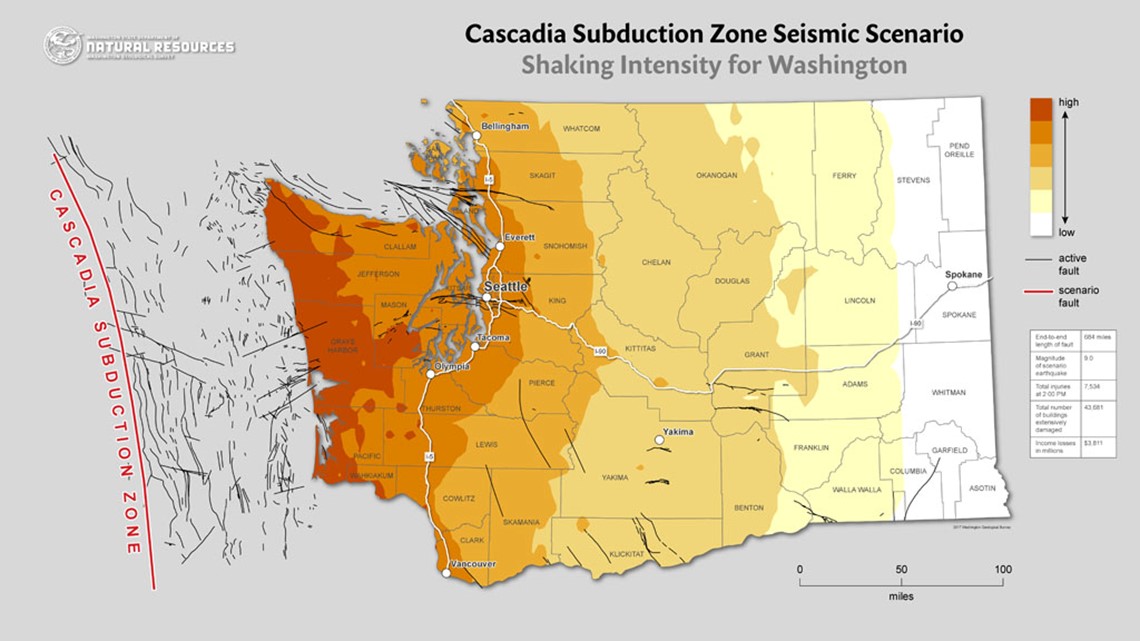

First, there’s the Cascadia Subduction Zone running roughly parallel to the Pacific Coast from northern California past the northern tip of Canada’s Vancouver Island.

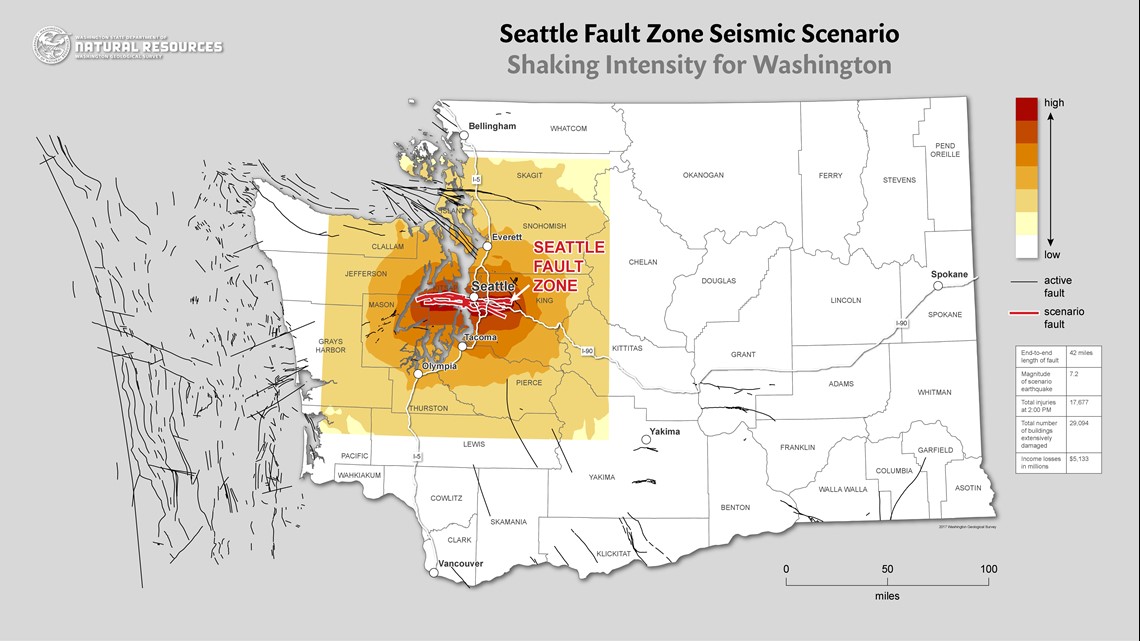

Second, the Seattle Fault, which runs east to west just south of downtown Seattle. It ends up near the Cascade Mountains and west onto the Olympic Peninsula.

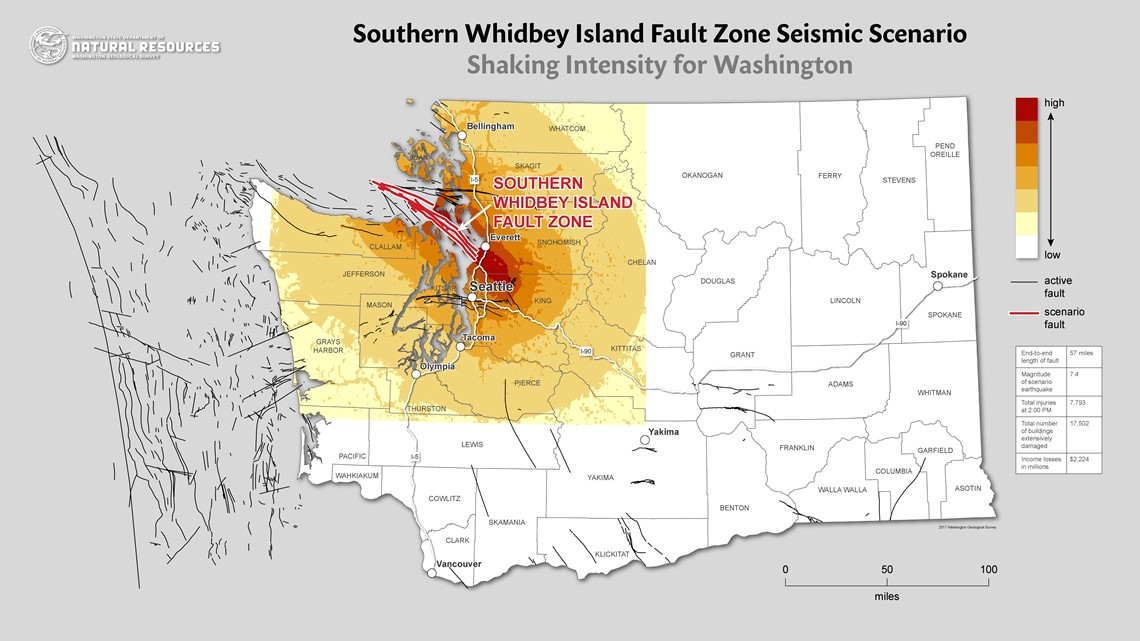

Third, the South Whidbey Island Fault running from northwest to southeast of the southern tip of the island.

These quakes are capable of magnitudes from 7 to over 9.

Every year Western Washington undergoes hundreds of earthquakes. Most of them are tiny, magnitude 1 or 2, and a map shows them since 1970 around the Puget Sound area.

All remind scientists of the potential that’s placed on larger faults, as the region is compressed by geological forces beyond anyone’s control.

On the map, a larger red dot near Olympia show the 6.8 Nisqually quake of February 2001. The 1965 and 1949 earthquakes of similar magnitude are shown on larger red dots nearby. Nisqually was responsible for $4 billion in damage, but nobody died as a direct result. Unlike California, we are reminded less often of the potential devastation.

“There is so much more work to be done within the basin and within all of Washington to understanding these faults,” said Corina Forson, the state’s chief hazards geologist for the Washington Geological Survey, part of the Department of Natural Resources.

Let’s take those faults in order.

Cascadia Subduction Zone

The Cascadia Subduction Zone is a giant fault running from Cape Mendocino, Calif. past Oregon and Washington and doesn’t end until it’s north of Vancouver Island in Canada.

You saw its potential in the 9.1 magnitude Tohuku earthquake and tsunami that hit northeastern Japan in March 2011. Tohoku killed nearly 16,000 people; most died as a result of drowning or being crushed in the tsunami.

Because Japan was so well prepared, most retrofitted buildings outside of the tsunami zone survived. This part of the Japanese coast had not seen this type of seismic rupture in some 800 years, and what failed was that walls built to keep tsunami waves were not high enough.

In Washington, we do not have tsunami walls. Along the coast residents may have between 20 and 30 minutes to get to higher ground. The Westport area is now the first in North America to have a community vertical evacuation structure, a building strong enough to resist earthquake and tsunami wave forces and give people a platform above the expected wave heights. That place is the Ocosta School.

Resources on tsunami danger and preparedness in:

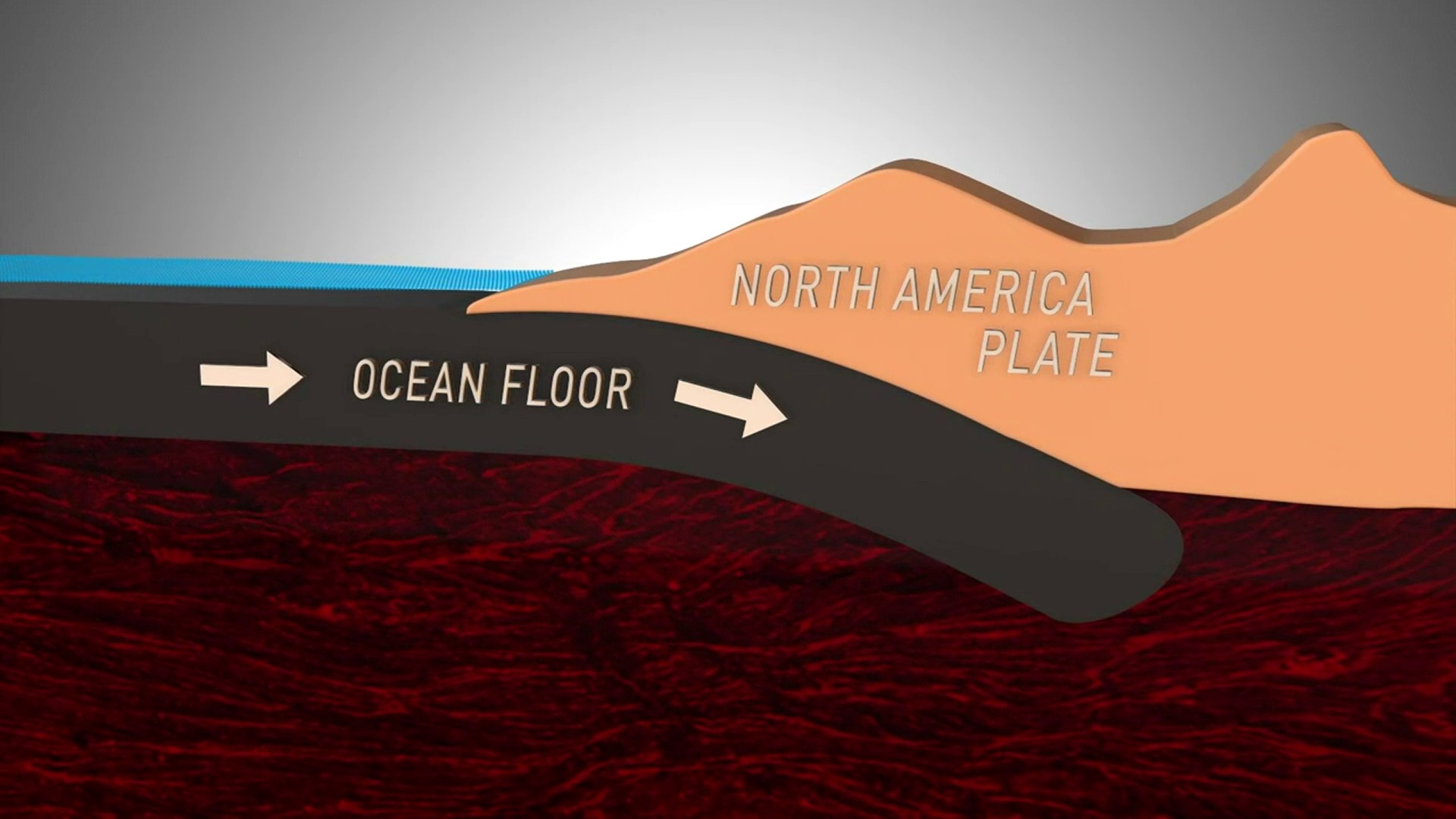

But the Cascadia Subduction Zone isn’t just a fault; it’s an overlapping joint between tectonic plates, parts of the Earth’s crust that float on layers of molten rock.

There’s a reason the lands around the Pacific Ocean are called the “Ring of Fire.” The earthquakes, tsunamis, and the proximity of volcanos are all part of the same system.

The coast is now the home of one of the state’s largest network of warning sirens called All Hazard Alert Broadcast (AHABs). But Forson says you also need to know what to do when the shaking happens.

There are also tsunami evacuation signs on the highways. Westport currently is the only location with a vertical evacuation structure designed for a tsunami.

“We do not encourage people to evacuate in vehicles. We’re working on pedestrian evacuation maps that show the best routes for pedestrians to take to evacuate,” said Forson. “You just need one person to crash or a power line to fall over the road, and the roads are unusable.”

“That’s why we’re pushing for a lot of vertical evacuation structures to be built – hotels or schools, because it’s not an easy problem to solve,” he said.

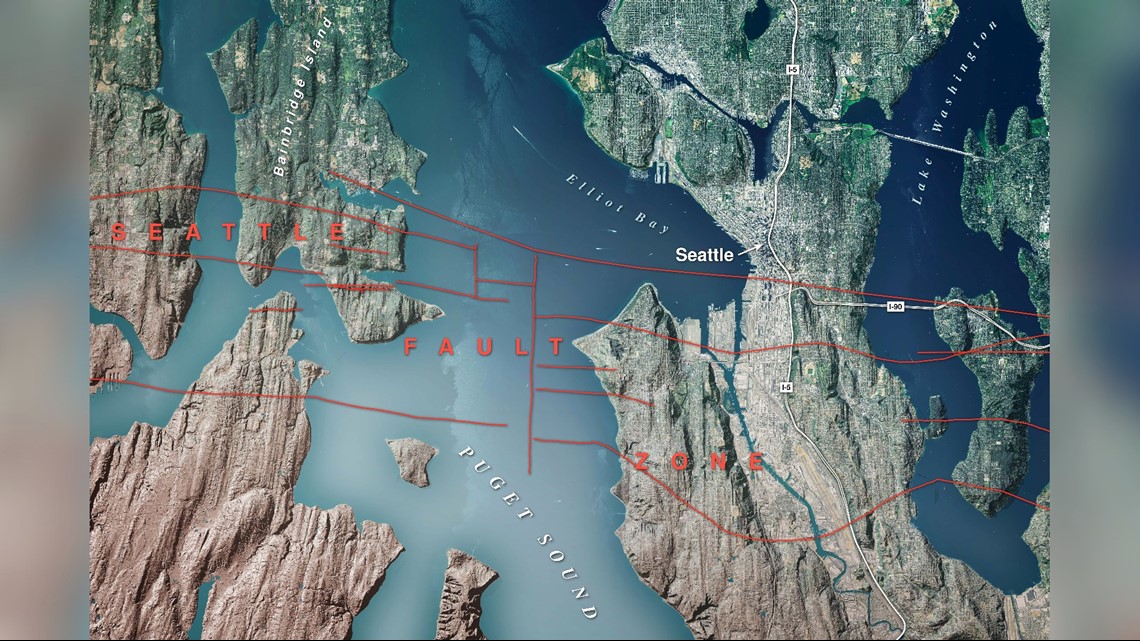

Seattle Fault

Moving inland, consider the Seattle Fault.

It’s considered capable of a magnitude 7. That may not sound like much more than the magnitude 6.8 quake of 2001 based on the numbers, but that the Nisqually quake occurred some 30 miles underground. Then consider that the Seattle Fault is a complex of faults with various branches that run at or just below the surface.

“The risk is complicated, but there are millions of people who live in the Seattle area,” said Forson. “What we know about this fault is that it’s ruptured may times in the past…it will happen again. We just don’t know when.”

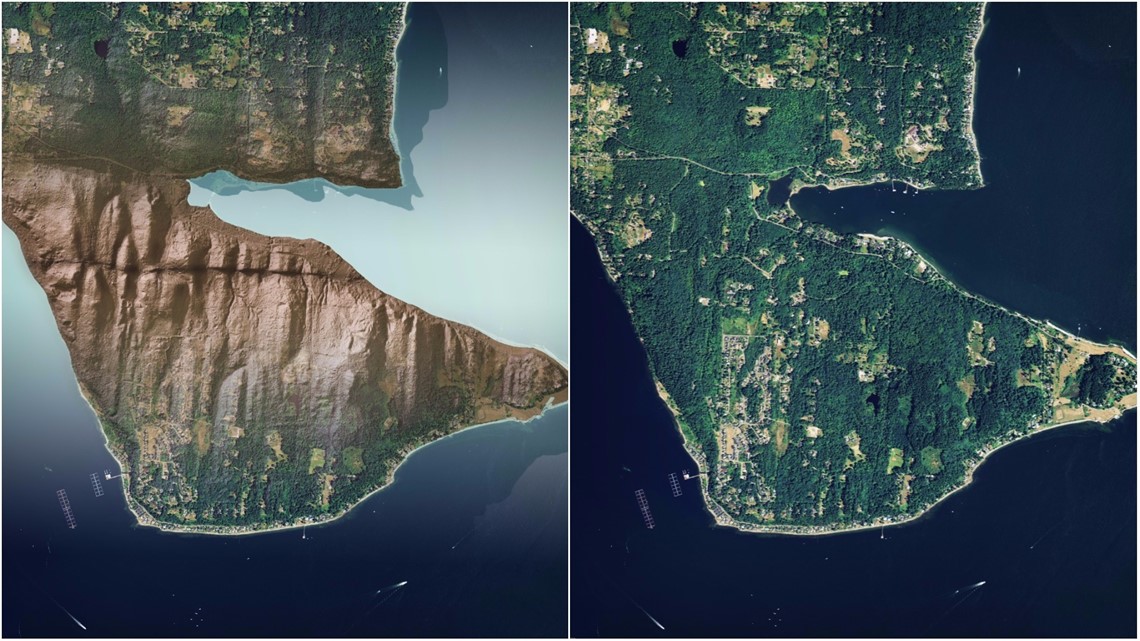

Across the northern portion of Bainbridge Island, light radar or lidar images taken from airplanes clearly show what geologists say is the Seattle Fault running right on the surface. Another piece can be seen under the elevated lanes of northbound Interstate 5 in South Seattle not far from the Rainier brewery.

The Seattle Fault is also likely to create a tsunami that would inundate Harbor Island and much of SODO, Interbay, and the waterfront. It could also create dangerous currents and hazards to the north including Everett.

Related: Geological hazard maps via Department of Natural Resources

What scientists don’t know is its timing interval.

“The last time was 1,000 years ago between 900 and 903 A.D.,” said Forson. “It will happen; we don’t know when.”

What about the localized tsunami risk? In the 1990’s, scientists produced an animation that shows inundation, and people won’t have much time to run to higher ground. In some areas getting up a hill to higher ground will be difficult. Some people in places like SODO and Harbor Island may have to flee to higher floors in a building.

South Whidbey Island Fault

The South Whidbey Island Fault is also dangerous.

It’s significantly larger than the Seattle Fault, and South Whidbey could hand us a magnitude 7.5 earthquake. That could spell trouble not only for its namesake island but for south and north King County and further west.

“The crustal faults – the Seattle Fault, the South Whidbey Island Fault, the Tacoma Fault – those are less well known,” said Forson.

Forson said more research needs to be done.

And while scientists keep digging for more information and more situational awareness of what we face, the other problem is human.

“A lot of people are transplants,” Forson said. “They didn’t grow up here, they haven’t heard this story. So they don’t necessarily know the threats they face.”

Join KING 5’s Disaster Preparedness Facebook group and learn how you and your community can get ready for when disaster strikes.

Why is KING 5 focusing so much on disaster preps? It's certainly not to scare you. Earlier this year, we began the task of creating a disaster plan – how this station would deliver the news if a major disaster struck the Pacific Northwest.

We began by consulting state emergency planners, the Red Cross, medical professionals, even other newsrooms.

What we got was a BIG wakeup call.

Emergency planners all had a simple message: It's not IF a disaster will happen, it's WHEN. Earthquakes. Volcanic eruptions. Devastating wind storms. Floods. Mudslides.

The experts say few are ready. And being ready means being able to support yourself, your loved ones, your neighborhood for 2 weeks. Because after a region-wide event, it could take that long for help to come from the rest of the country and world.

So our plan to make a plan for KING inspired us to help all our viewers understand what they need to do to get prepared.

The people of KING 5 are like you: We live and work here. Most of us have families, friends and pets who we will need to care for.

Our full day of coverage is a first step for us and, we hope, for you.