KLICKITAT COUNTY, Wash. — Warning: This story contains details of a body's decomposition that some may find hard to read.

Deep within Klickitat County, thick with fir, oak and pine trees, is the Herland Forest Natural Burial Cemetery. It’s a place where even in the dead of winter, there’s a certain life-giving energy under foot from the 54 people buried there. Forest Steward Walt Patrick calls them the "guardians of the forest."

“These are people who have chosen to use their final remains, their final option, to help protect this forest from being clear-cut and developed,” said Patrick.

Five years ago, the forest became a licensed, nonprofit natural burial cemetery where bodies go into the ground without chemicals.

“Most people don't know that green burial even exists,” said Patrick, whose background is in chemistry and physics. “Up until about 150 years ago, this was how everyone was buried.”

It’s a process Patrick says gives back to the environment.

“If you get oxygen to decomposing flesh, the bacteria will decompose into carbon dioxide, which is easily consumable by plants,” said Patrick. “Without that, it will convert to methane, and methane is a 20-times worse greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.”

Patrick calls it a natural organic reduction, a process that up until recently was only allowed to happen underground. In 2019, Washington became the first and still only state in the country to allow above-ground composting as an alternative to burial or cremation. Right now, Herland Forest is one of just three locations offering the service, which costs $3,000.

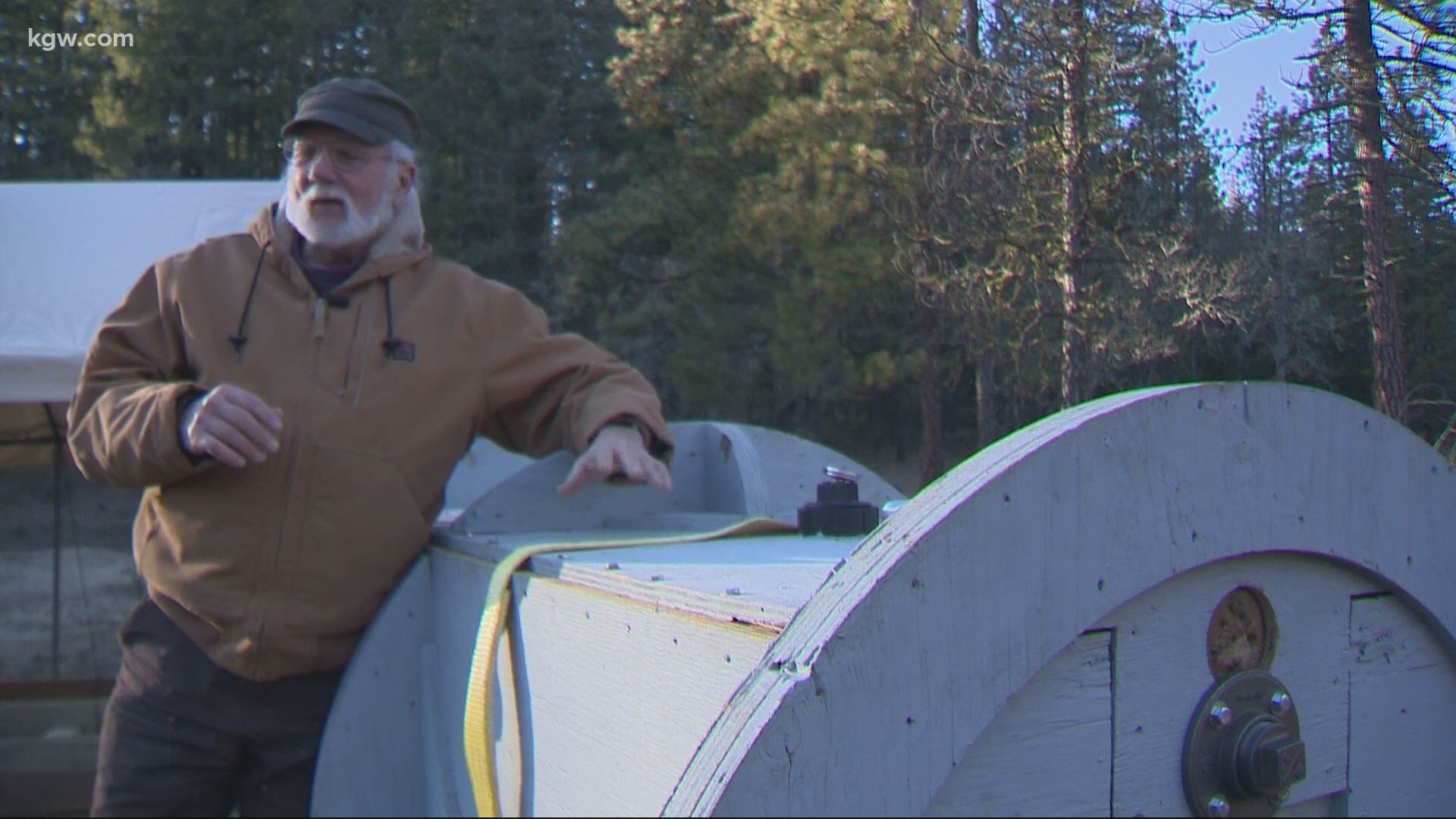

Patrick explained the process starts by placing a body — or “investment," as they’re referred to — inside a 1,000-pound cylinder-shaped, wooden cradle. The body is layered between a cubic yard of wood chips and a series of bacteria, protozoa and fungi. The mixture is rotated regularly while its temperature is kept between 130 and 155 degrees.

Patrick said their first investment has been decomposing in the cemetery’s cradle since December. By law, the remains must reach 131 degrees for three days to kill salmonella and other organisms to ensure the compost is safe. It’s a process Patrick said takes longer in the winter months.

“We work on nature's clock,” said Patrick. “People are going to be dead for a long time. There really isn't any hurry to get this done. We'd much rather take our time and get it done right.”

Once the natural organic reduction is completed, the remains are sifted through a screen to separate out nonorganic material like joint replacements, titanium plates and teeth. What's left is enough compost to fill four, 55-gallon drums. Loved ones can take as much of it as they want and dedicate the rest to the forest, where it will be put to special use.

“We'll use it to plant trees, and then they'll have a memorial tree for who and what they are,” said Patrick. “If somebody just wants to become a tree, then this is the best way to do it.”

Patrick has spent more than 30 years in the Herland Forest, investing in the environment and helping others do the same. When his time comes, he has no plans to leave.

“Let death bring the land and me together forever rather than be evicted just because you're dead.”