Washington's Baker River sockeye salmon run smashes record, despite hydroelectric dams

Salmon run once on the brink of extinction returned this year in record-crushing numbers in Skagit County. Much of the credit goes to a privately-owned utility.

Members of the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe, Washington state resource managers, and recreational anglers alike are all stunned by the historic, record-setting run of sockeye salmon on the Baker River in Skagit County. It’s a milestone moment on the Baker that nearly saw the species go extinct in the 80s and early 90s.

An unlikely player, a privately-owned utility company Puget Sound Energy, is largely credited with the remarkable turnaround.

“To their credit, they worked with us,” said Scott Schuyler, natural resources director for the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe. “It was amazing to see these large numbers, and it was a little bit of a shock to see them come back in such high numbers. It’s one of the biggest things that have happened to our people.”

Not that long ago the run was in peril, in part because of Puget Sound Energy’s two hydroelectric dams on the Baker, built 100 years ago, that create carbon-free electricity for approximately 1.2 million customers in Washington state.

The utility company attempted to mitigate the harm brought to fish by installing a fish ladder and later by putting in aerial trams to transport salmon, but the efforts weren’t working.

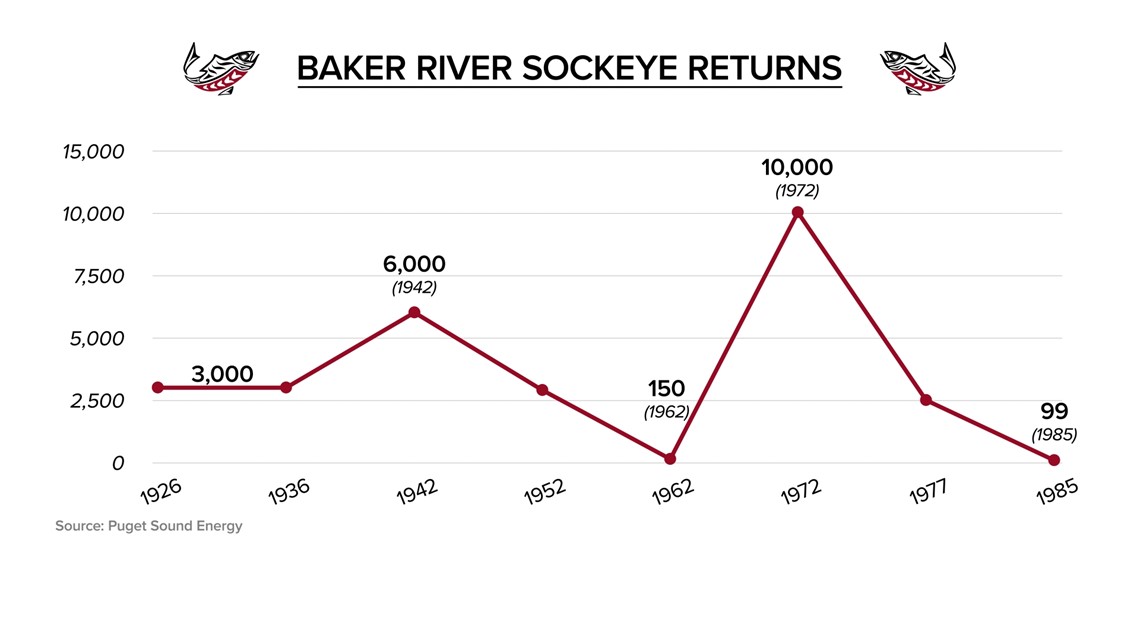

The run struggled from the 1920s to a low in 1985 of just 99 sockeye returning.

Dams were partly to blame for crushing the salmon runs, and with it, the heart and soul of the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe, whose members fished the Baker River for 10,000 years. A way of life was on the brink.

“Part of us would have been gone,” Schuyler said. “Part of our history, part of our culture. That’s why we continue to be proactive and speak for the salmon. The salmon must survive, just as we’ve survived.”

Sockeye coming back to the Baker Puget Sound Energy has taken action to improve fish passage systems, with record-breaking benefit

Officials at Puget Sound Energy (PSE) knew the clock was ticking and formed a team of specialists, including tribal and regulatory stakeholders, to put together an action plan.

“It was very concerning. We thought we were going to lose the stock entirely. We were close,” said Arnie Aspelund, PSE senior resource specialist. Aspelund began working for the utility when the run was at its lowest point in the mid-80s.

“We put our heads together in a collaborative process to try to find the pieces that work,” Aspelund said.

Under provisions of a 2008 federal license to continue to operate the hydroelectric project, PSE installed one of the most sophisticated fish passage systems in the country. It involves trapping fish, then hauling them around the dams in “fish taxis.” The sockeye are then shot back into the water through pipes to access the blocked habitat. PSE also built a state-of-the-art hatchery to cultivate and breed fish in an enclosed environment — a multi-million-dollar, year-round investment by a utility.

“It aligns with our values,” said Aspelund of PSE. “This has been the right thing to do from the get-go.”

The work has paid off.

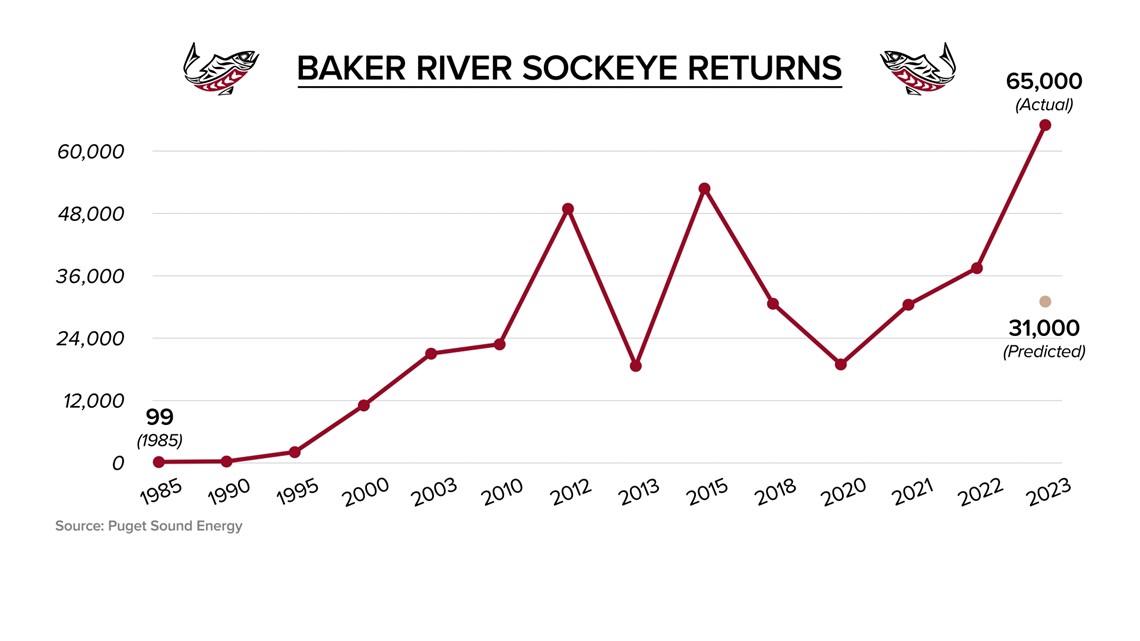

The Baker River sockeye returns have dramatically increased since the dismal low of 99 fish in 1985. More than 52,000 sockeye came back in 2015, the previous record. This year 31,000 were predicted to return. But the actual number smashed the forecast with 65,000 sockeye coming back to the Baker.

“It’s a labor of love to see all these fish come back,” said Randy Mason, the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife hatchery operations manager for region 4 North. “It’s remarkable. From where it was to where we are now is remarkable. You don’t get success stories like this, but this is one of them.”

The surprising numbers allowed Upper Skagit Indian Tribe members to extend their allotted number of fishing days on the river – a stark contrast from the eight decades the tribe couldn’t fish for Baker sockeye at all.

“It was a real positive thing to see this big run this year and a big milestone for our people,” Schuyler said. “I never thought I would make it to the day to see that.”

Seattle City Light's dams on the Skagit River have no fish passage The utility company agreed to install a fish passage six months ago, but so far, there's no agreement to do so

The Baker River is a tributary of the Skagit River, where another utility, Seattle City Light, owns and operates three hydroelectric dams. The project provides approximately 20% of Seattle’s electricity. But unlike PSE’s operation, City Light has no fish passage infrastructure. Seattle's public utility has instead invested in fish enhancement by adjusting water flows through the dams and by purchasing thousands of acres of land aimed at preserving fish and wildlife habitat.

For years, the lack of fish passage has been at the center of strained negotiations between City Light, tribes of the Skagit Valley, and government agencies as the utility works to obtain a new license from the federal government to operate the project.

While PSE accepted responsibility for the harm their dams bring to fish, Seattle City Light has fought that notion.

In a two-year investigation beginning in 2021, the KING 5 Investigators exposed City Light denied their dams hurt fish, and even bragged in literature and on its website that the project helped salmon. KING found the utility relied on outdated science that showed salmon were never able to access the habitat blocked off by the city’s dams, so installing fish passage wasn’t necessary. The only scientists involved in the relicensing who believed that theory worked for Seattle City Light.

After four rocky years of talks, the then-CEO and general manager of City Light announced they had finally agreed to install fish passage on the Skagit.

“I think it’s a big step, it’s intended to be one,” said Debra Smith in April. “This represents a piece of restorative justice here. What I see us doing here is saying ‘we understand that we have impacted you and this was your land.’ And for this country, that has such a history with Native American people, such an ugly history, I think it’s really important.”

That was six months ago. To date, there’s still no agreement signed and no official commitment by Seattle City Light.

“We’re just hoping the city follows through on what it stated it was going to do,” said Schuyler of the Upper Skagit Tribe. “We’ve put up with this for 100 years. I want to make it clear; the Upper Skagit Tribe needs to have fish passage over these three dams to make this right.”

Seattle City Light responds The goal is to expedite the project after federal approval, utility says

In a statement to KING 5, a City Light spokesperson said the utility is still dedicated to installing the infrastructure.

“Our April 2023 (federal license application) outlined a comprehensive fish program that included a plan for fish passage across all three dams. We remain committed to implementing the fish passage plan,” wrote City Light Media Relations Manager Jenn Strang. “However, (federal) approval is required before any fish passage implementation and the (government’s) review of the license application is expected to be completed in 2-3 years. During this time, City Light continues to push the project forward by working with Tribes, (and federal and state natural resource regulators) with the goal of expediting implementation after (federal) approval.”

While salmon runs on the Skagit continue to struggle, production on the Baker is giving the tribe hope.

“This is a victory," Schuyler said. "It just shows that through collective effort and collaboration things can be positive and you can affect change in the right direction."