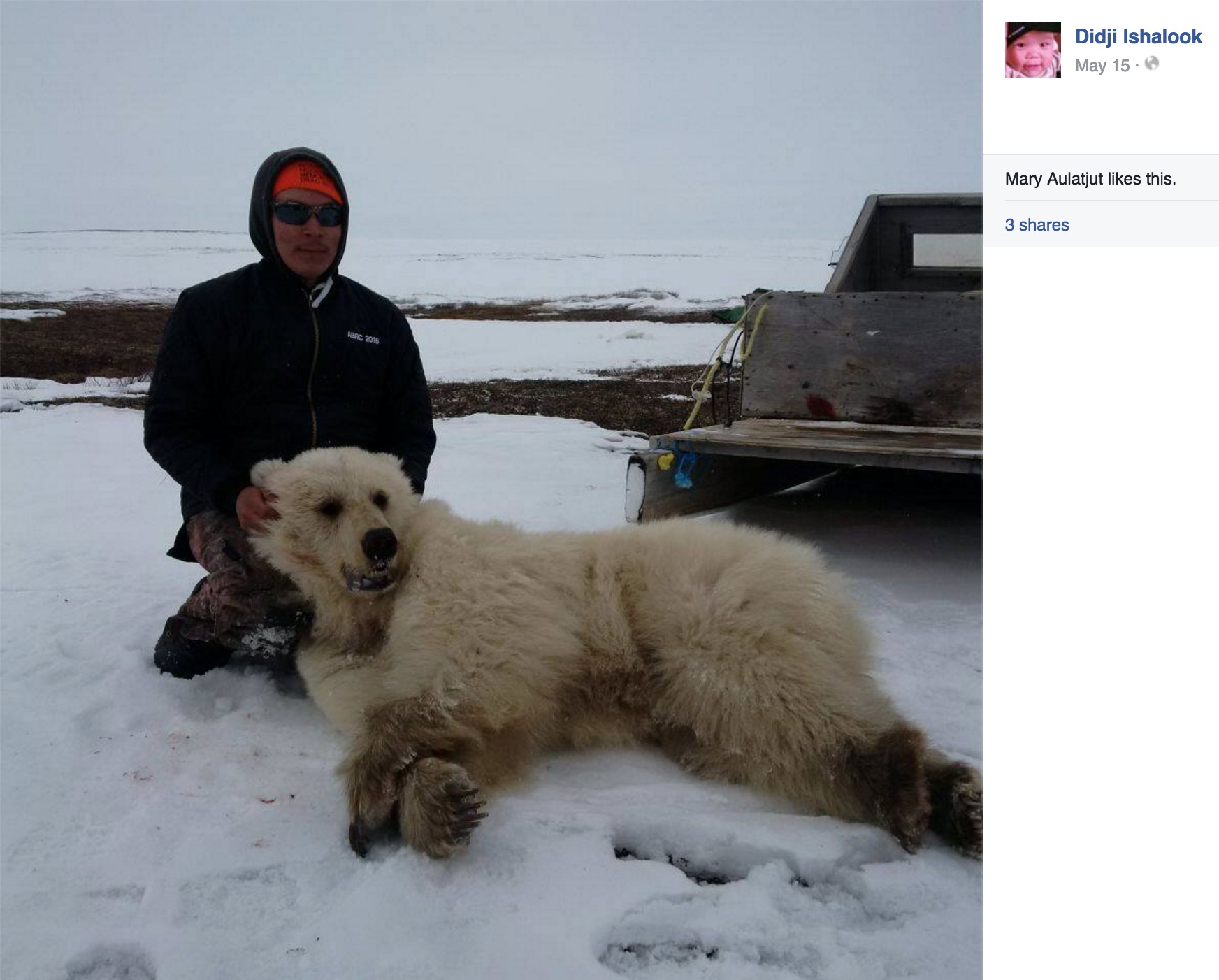

Earlier this month, Didji Ishalook took aim and fired at a bear on a hill near his home in the Canadian Arctic. When the 25-year-old approached the fallen bear, he noticed it looked odd.

"It looks like a polar bear but...it's got brown paws and big claws like a grizzly. And the shape of a grizzly head,” Ishalook, who lives in Arviat, later told CBC News.

Experts now think the bear is a grizzly-polar bear hybrid, the result of increasingly frequent interbreeding believed to be aided by climate change.

Sightings of such hybrid bears—called “pizzlies” if the father is a polar bear and a “growler bears” if the father is a grizzly – have increased in recent years as the Arctic has warmed at twice the rate of the worldwide average, The Guardian reported. Yet the hybrid beasts’ elusive nature means little is known about them.

Ice in the Arctic, on which polar bears roam to hunt and devour seal, is waning.

The ring of ice around the North Pole measured in January was the smallest that it’s ever been in that month since recording began, according to National Snow and Ice Data Center figures reviewed by Vice News.

Dave Garshelis, a research scientist with the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, told CBC News he believes the hybrid bears, including Ishalook’s, are occurring more frequently due to climate change.

Less ice makes it harder for the bears to hunt, Garshelis said, pushing them onto land farther south. At the same time, the warming climate has allowed grizzly bears to move farther north, creating more opportunities for the genetically similar polar bears and grizzlies to cross paths.

Chris Servheen, a bear biologist at the University of Montana, told Canada’s ABC News that sightings of grizzly-polar bear hybrids remain rare and noted that humans have made little contact with such bears.

With so few sightings, it’s difficult to know how many of the bears exist, Servheen said, and the bears’ solitary nature — both grizzlies and polar bears avoid humans — means scientists know little about their temperament.

An Idaho man named Jim Martell shot the first recorded “grolar bear” in Canada’s Northwest Territories in 2006, according to National Geographic.

A few years later, in 2010, the lead author of a commentary on the bears published in the journal Nature warned hybridization “can be the final straw in loss of species.”

Servheen agreed.

"It is not a good thing for the future of polar bears that we see this hybridization occurring, and it's not going to result in some kind of new bear that is successfully living in the Arctic," he told Vice News.

Follow Josh Hafner on Twitter: @joshhafner

![635996232249291027-Screen-Shot-2016-05-23-at-4.53.32-PM.jpg [image : 84817004]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/c24932b0f5655393a67736b0a9b5df2ed5fd7834/c=103-0-1743-1402/local/-/media/2016/05/23/USATODAY/USATODAY/635996232249291027-Screen-Shot-2016-05-23-at-4.53.32-PM.jpg)