PIERCE COUNTY, Wash. — A $5.5 million water treatment center filters millions of gallons a day for customers of the Lakewood Water District. It sits less than a mile away from Joint Base Lewis-McChord.

It’s one of two treatment centers that was created for one job: eliminate "forever chemicals" from Lakewood’s water supply.

“By the time it hits the bottom it’s undetectable," Lakewood Water District engineering manager Marshall Meyer explained.

Lakewood is one of many water systems going to extraordinary lengths to address the threat that health officials are still trying to understand.

The synthetic compound Polyfluoroalkyl, commonly referred to as PFAS, or "forever chemicals," has been used in common products for decades.

Scientists are now linking the chemicals to a growing list of health risks that includes cancer, fertility problems and kidney disease.

KING 5 reported on a mobile home park in Kitsap County identified by a Department of Health dashboard as one of the communities with PFAS levels that exceed statewide standards. People that live there said they only drink bottled water to stay safe.

The managers of that water system said one of the biggest barriers to eliminating PFAS is cost.

Lakewood Water District has 31 active wells that can pump out more than 20 million gallons of water a day, but longtime general manager Randy Black said that got a lot more complicated in 2016.

“We had to make that decision in order to keep public trust and confidence,” Black said.

Joint Base Lewis-McChord announced PFAS detection on the base, and that fall the nearby water district began detecting levels.

"We need to make sure their problem is something that's not our problem. So that led us to the testing," Black said.

PFAS has been identified near more than 100 military bases around the country. The chemicals are believed to come from the foam used in firefighter training exercises and have now seeped into water systems.

“These compounds are persistent. We call them persistent organic pollutants. They can stay in our environment for about 1,000 years,” University of Washington toxicology professor Judit Marsillach said.

Lakewood’s wells are in the same aquifer as JBLM.

The water district received a $5 million state grant, but over the next 30 years, they estimate upkeep and replacements to the treatment facilities will cost tens of millions of dollars.

To combat those costs, the district has sued 13 manufacturing companies that used harmful chemicals. They also sued the Department of Defense.

“That would help instead of us having to either borrow money or go to the legislature and ask for more grants,” Black said.

Competition for that money will become stiffer as soon as next year. That’s when the Environmental Protection Agency will set what’s called a maximum contaminant level. It will be the first time the federal government will require water systems to test for the chemicals.

The level is expected to be stricter than the current state recommendation.

For Lakewood, it will mean replacing their filters three years faster.

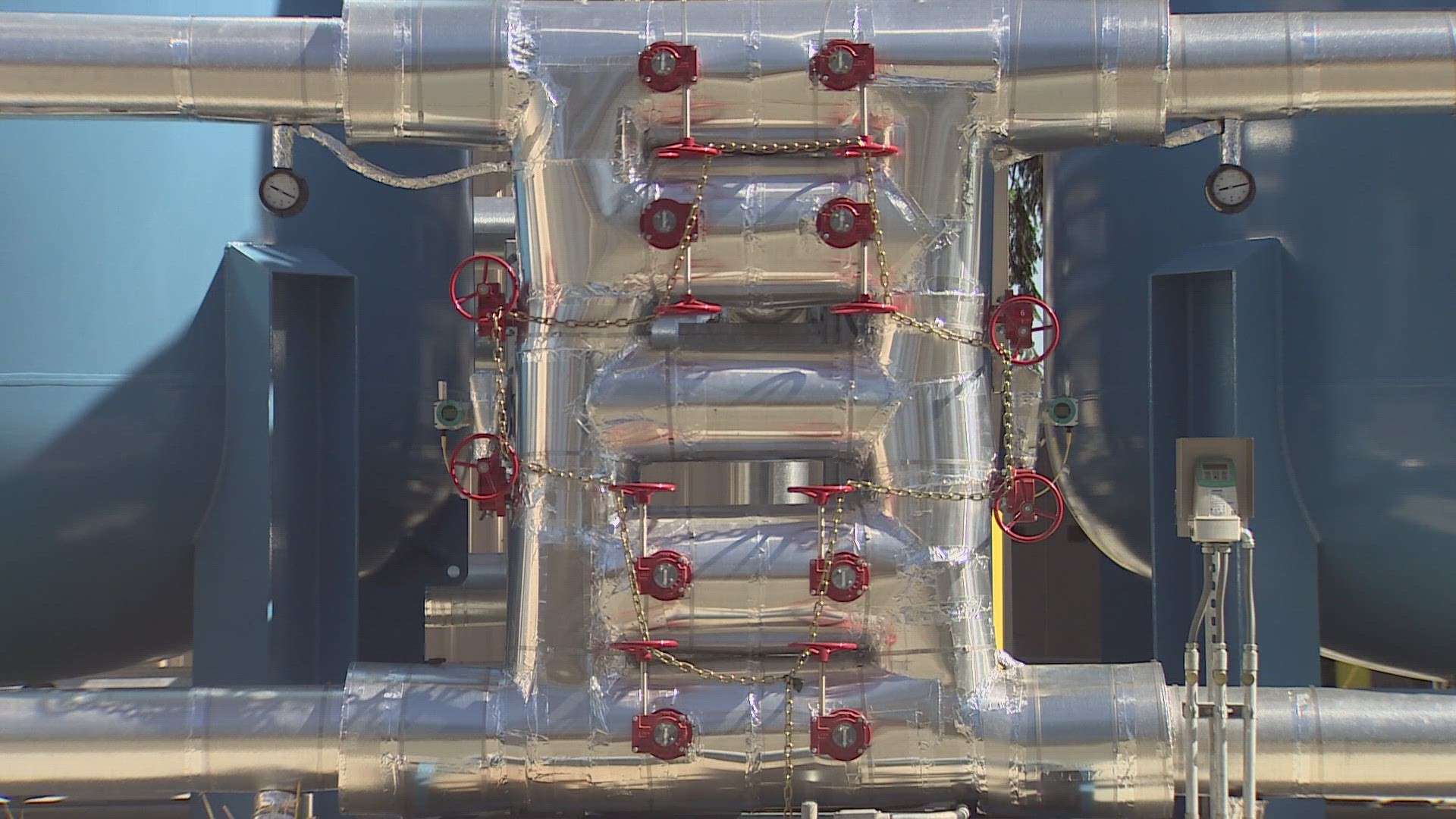

"With EPA’s proposed levels we're looking at about two years of life on these,” Meyer said pointing towards the treatment facility. “Each one of these vessels is around $100,000 to replace the media in it."

Black said so far rates have not been impacted, but what it means for your water bill going forward will depend on how many grants and how much money is awarded in court.

“To what extent, I don't know yet,” Black said.

Several companies that make PFAS chemicals agreed to pay $1 billion to remove PFAS from water systems across the country.

3M, the company that makes products like masks and post-it notes, said it would pay $10 billion to water suppliers that have detected PFAS. 3M is one of the 13 companies Lakewood is suing.