SILVER SPRING, Md. - A tiny piece of metal that changed the course of history is here, at the National Museum of Health and Medicine outside Washington, DC.

"Founded as a center for the study of battlefield medicine during the Civil War," explained Tim Clarke, Deputy Director for Communications. "And 150 years later we have a collection of 25 million objects."

A stroll through the museum reveals startling discoveries around every corner, from the foot and leg a victim of elephant man disease, to a massive trichobezoar, or human hairball.

"It was collected from the stomach of a 12-year-old girl," Clarke said.

This free museum, operated by the Department of Defense, pulls no punches in its mission to educate. Here you can see the plaster casts that were used more than 150 years ago to document the progress of wounded soldiers undergoing transformative surgery. They are picture-perfect 3-D impressions of actual faces. Human skeletons of every size illustrate the growth of the human body. Perforated skulls reveal lifesaving craniotomies, a procedure to relieve the swelling of patients' brains. It's a technique perfected on the battlefield and still used today.

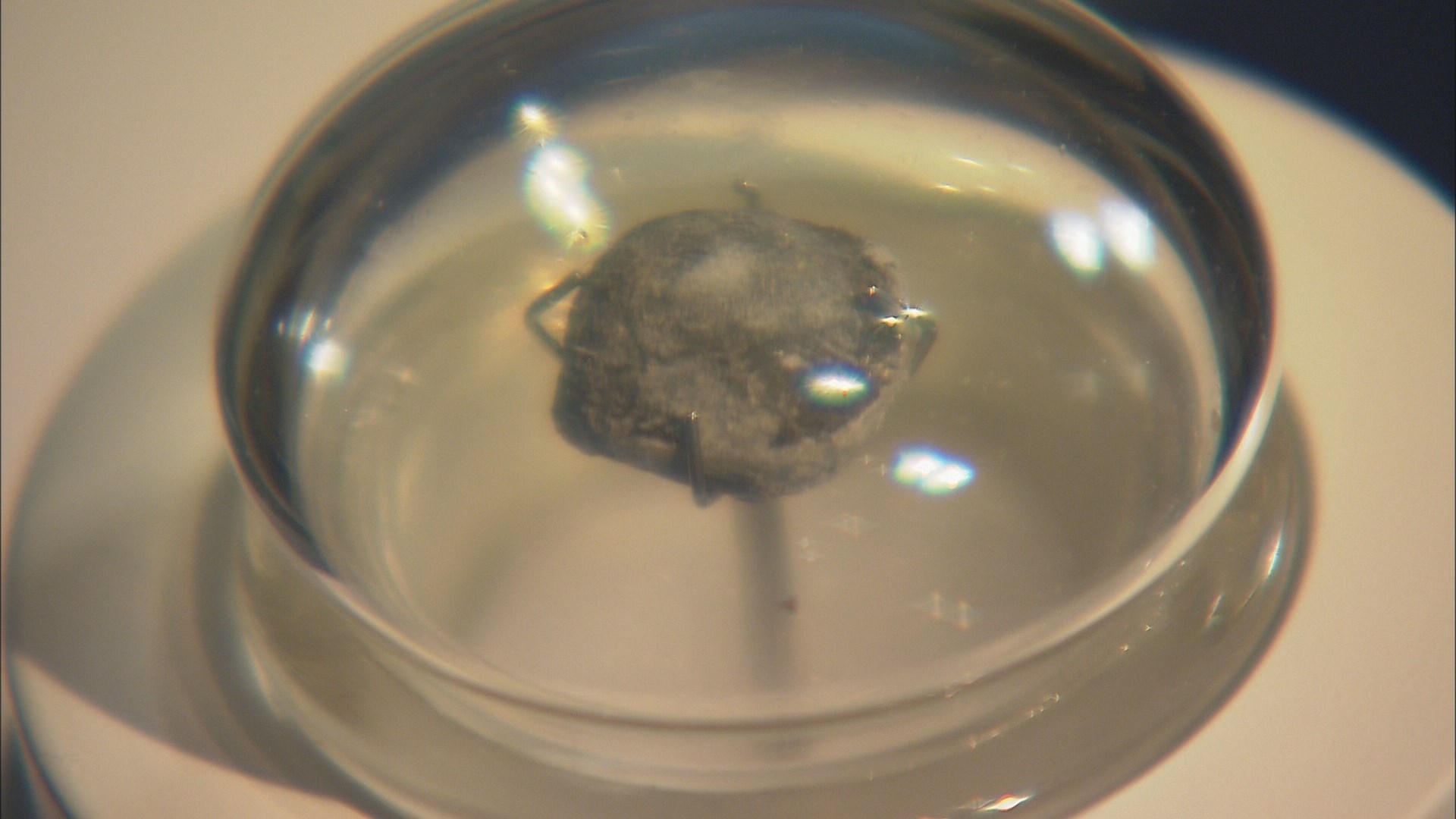

The most astonishing section of the museum is the presidential collection. In addition to Lincoln's skull fragments and the fateful assassin's bullet, visitors can gaze upon the actual blood of the president, stains left on the clothing of an autopsy assistant.

"When he got home he realized his shirt cuffs were stained with the president's blood," said Clarke.

There are other morbid artifacts from our fallen leaders, including the spine of James A. Garfield, also cut down in office.

"They kept that part because it was evidence of the crime," Clarke explained. "That part of the spine shows the path of the bullet that killed Garfield."

Swabs of the cancer that took the life of President Ulysses S. Grant can also be seen in the exhibit.

These sometimes gruesome displays awaken the senses and stir the mind.

"What makes you tick. How you work," said Clarke.

They remind us that, from Commander in Chief to the common man, we are all very human.