This article was published in partnership with NBC News.

TACOMA, Wash. — The doctor delivered her report to authorities with striking certainty.

“Ellie Carter is a victim of medical child abuse,” Dr. Elizabeth Woods wrote in May 2018, indicating that Megan Carter had abused her 5-year-old daughter by pushing for excessive and harmful medical treatments. “This is life threatening, and she is at imminent risk if her mother is involved in her care.”

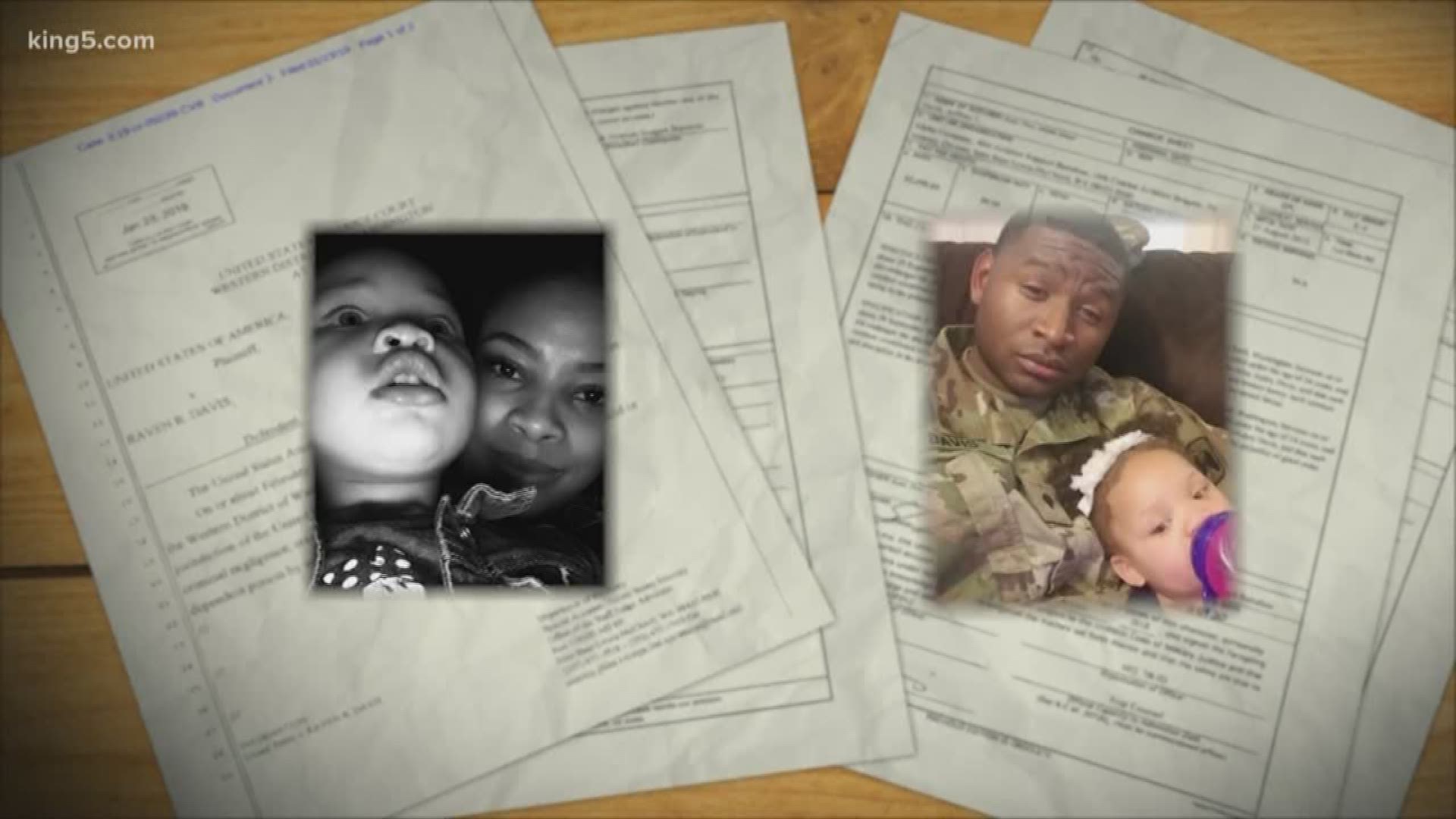

Based on that warning, Child Protective Services took custody of Ellie and her 8-year-old brother, and authorities in Pierce County opened a criminal investigation, though charges were never filed. For months afterward, Carter was forced to live apart from her family — a separation that she said traumatized her children and sent her into a deep depression.

Authorities in Washington gave significant weight to Woods’ opinion. The 38-year-old pediatrician at Mary Bridge Children's Hospital in Tacoma is regarded as one of the state’s pre-eminent experts in identifying subtle signs of child abuse.

Nonetheless, a review of court records and interviews by KING 5 and NBC News found that she lacks key medical training for assessing potential abuse cases.

At a court hearing in May 2019, a year after the initial allegation, Carter's lawyer asked Woods about her background under oath. How did she become one of the state’s leading authorities in diagnosing child abuse? Had she received specialized medical training or passed a certification test?

No, Woods replied, she hadn’t done the three-year medical fellowship that a doctor must complete in order to become a child abuse pediatrician, and, no, she hadn’t passed the exam required to become board certified in the field.

But, Woods added, neither have most doctors who specialize in identifying child abuse.

“There are approximately 250 of us nationwide that function as child abuse consultants,” Woods said that day in court, according to an audio recording of her testimony. “And a very small minority of those have received training, as the training just started about three years ago. So I was already well into my career prior to that being offered and have established my credibility through extensive experience.”

But that wasn’t true. Among the small cadre of doctors who perform child abuse assessments on behalf of Child Protective Services authorities in Washington, Woods is the only one who both lacks decades of experience in child abuse and also never completed immersive fellowship training that’s now required of doctors entering the field, KING 5 and NBC News found.

Contrary to Woods’ testimony, there are more than 375 child abuse pediatricians certified by the American Board of Pediatrics in the U.S., all of whom have either completed an extensive fellowship program — first offered, not three, but nearly 15 years ago, while Woods was still in medical school — or spent years examining cases of suspected abuse prior to the creation of the medical subspecialty in 2009. The doctors are trained to differentiate accidental from inflicted injuries, which child abuse pediatricians say makes them better qualified than other doctors to determine whether a child has been abused. At least three physicians have met those qualifications and are practicing as board-certified child abuse pediatricians in the state of Washington.

Woods is not one of them.

Despite her lack of fellowship training, state child welfare and law enforcement officials in Washington have granted Woods remarkable influence over their decisions about whether to remove children from parents or pursue criminal charges, KING 5 and NBC News found. In four cases reviewed by reporters, child welfare workers took children from parents based on Woods’ reports — including some in which Woods misstated key facts, according to a review of records — despite contradictory opinions from other medical experts who said they saw no evidence of abuse.

In one instance, a pediatrician, Dr. Niran Al-Agba, insisted that a 2-year-old child’s bruise matched her parents’ description of an accidental fall onto a heating grate in their home. But Child Protective Services workers, who’d gotten a call from the child’s day care after someone noticed the bruise, asked Woods to look at photos of the injury.

Woods reported that the mark was most likely the result of abuse, even though she’d never seen the child in person or talked to the parents. The agency sided with her. To justify that decision, the Child Protective Services worker described Woods as “a physician with extensive training and experience in regard to child abuse and neglect,” according to a written report reviewed by reporters.

“That's what bothers me so much about this whole case is that they wrote that they took her opinion because she has extensive training,” Al-Agba said in an interview. “Where's the extensive training? I'm still dumbfounded.”

When questioned about her qualifications during Carter’s case, Woods stated that she worked on cases of suspected child abuse when she was a doctor in the Army, from 2007 to 2017. And she said that she regularly attends conferences and seminars focused on the detection of child abuse, though she acknowledged she hasn’t published research on the subject.

Woods did not reply to emails seeking comment and did not answer detailed questions from reporters. In a statement, a spokeswoman for Mary Bridge said hospital leaders could not discuss individual cases because of patient privacy rules, but defended Woods and the team she leads.

“Dr. Woods has specialized training and significant experience in the field of child maltreatment,” the statement said. “She has practiced as a child abuse consultant at several hospitals and has treated thousands of children over her many years of dedication to this field. She routinely completes continuing medical education, and is an ally to the vulnerable children of our community.”

Neither Woods nor the hospital answered questions about Woods’ lack of board certification or her incorrect explanation for why she never participated in fellowship training.

Dr. Desmond Runyan, a professor emeritus at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, played a leading role in establishing the child abuse pediatrics subspecialty more than a decade ago. He and others in the field said there’s a critical shortage of doctors with the expertise and willingness to examine children for signs of abuse, and for that reason, he said general pediatricians can and should testify in these cases — even if they never received fellowship training.

But, Runyan said, in order to lead a hospital child abuse program or to serve as a state’s primary medical expert, “I would absolutely prefer to have someone who was board certified.”

“And certainly in the case you’re describing,” Runyan said, “it sounds like one where you would want someone who is board certified.”

But Dr. John Leventhal, former medical director of the Yale-New Haven Children's Hospital child abuse program in Connecticut, said he does not believe new pediatricians necessarily have to complete fellowship training before becoming experts in child abuse. He said Woods’ lack of board certification did not raise a red flag for him, especially since senior child abuse pediatricians at nearby Seattle Children’s Hospital allow her to review cases and help train fellows.

“It means she’s got the expertise that’s good enough, probably excellent enough, to provide that kind of training,” Leventhal said.

Carter knew nothing about Woods’ background when the doctor first accused her of harming her daughter two years ago.

“I couldn’t understand why her opinion carried so much weight,” Carter said. “It was like, whatever Dr. Woods said, everyone just accepted it as fact.”

‘Show me proof’

The hospital visit that nearly destroyed Carter’s family started with a mysterious infection. Her typically spunky daughter, Ellie, then 4, had been listless for days, leading to a series of visits to her pediatrician but no answers. By the time Carter and her husband, Andy Carter, brought her to the emergency room at Mary Bridge Children’s Hospital in March 2018, the girl was deteriorating rapidly, medical records show.

Doctors connected her to a ventilator to pump air in and out of her lungs and gave her medicine to keep her blood pressure up.

It was the latest in a long line of hospitalizations for Ellie, who’d been born severely premature, at 24 weeks, and as a result suffered from developmental delays and chronic health problems, including serious breathing and digestive difficulties, according to her parents and medical records shared with reporters.

Carter had repeatedly credited Mary Bridge doctors with saving her daughter’s life. When Ellie was 6 months old, she wasn’t gaining weight, so a gastrointestinologist inserted a feeding tube in her abdomen to deliver nutrition directly to her stomach — a medical intervention that also left her prone to infections. Two months later, a pulmonologist ordered oxygen treatments to assist her underdeveloped lungs, according to Ellie’s medical records. Later, a neurologist prescribed anti-seizure medication after Carter and medical staff members reported severe shaking spells.

Along the way, Ellie became one of Mary Bridge’s most famous patients. The hospital put her image on banners and shared her harrowing story in messages to donors. In 2017, when Ellie was 4, NFL star Richard Sherman visited her in the hospital after a marketing staff member invited him to meet his young fan — a touching moment that drew national media attention.

Carter, a former nurse and stay-at-home mom, committed to being Ellie’s primary caregiver, managing her many medical treatments and appointments.

But a few days into her hospitalization in spring 2018, while Ellie was still connected to life support, a worker for Child Protective Services entered her room and told Carter that someone had raised concerns about her ability to continue caring for her daughter.

“Where is this coming from?” Carter remembers asking, but she said the worker did not answer her questions about who made the report or what was alleged. And for weeks afterward, nothing came of it.

Then in early May, as Ellie’s body continued to fight the infection, Woods asked to speak with Carter. As the head of the hospital’s child abuse intervention team, Woods had come to inform Carter that, because of unresolved concerns about Ellie’s medical care, Carter no longer would be allowed to be alone with her daughter at the hospital. A nurse or another member of the medical staff would supervise her at all times, Woods explained, and the hospital room would be monitored by video.

Carter said she was baffled by the monitoring requirements.

“I’ve always done everything in my power to take care of my children, yet now I was being treated with suspicion,” she said. “But my main focus at that time was getting Ellie healthy, because she was still really struggling at that point.”

For days afterward, Mary Bridge staff watched Carter’s every move at her daughter’s bedside, even as they slept, according to Carter and records.

Then, six weeks into Ellie’s hospitalization, just as the girl was starting to show signs of recovery, two hospital social workers showed up. They said they needed to speak privately with Carter and her husband. The workers led them to another room, where two police officers awaited.

They were there to escort Carter out of the hospital. Woods had contacted authorities and reported Ellie as a confirmed victim of medical child abuse — a rare form of maltreatment in which a caregiver exaggerates or induces a child’s health problems in order to harm her with needless medical treatments. In her message to authorities, Woods reported that she had video evidence of Carter tampering with her daughter’s medicine, though nobody explained that to Carter or her husband at the time.

Carter wept as the officers walked her out of the hospital, and soon after, a judge granted a request by Child Protective Services to place Ellie and her older brother, Spencer, in protective custody. Under the court order, Carter would not be allowed to live in the same home as her children, and pending the outcome of the state investigation, she was barred from being around them unsupervised.

Once Ellie was released from the hospital, her father would take her and her brother to stay at his parents’ house nearby. The grandparents could help care for the children while he worked as the sales manager of a car dealership.

But Woods wasn’t satisfied with the arrangement, according to notes in Ellie’s medical records. She reported writing messages to Child Protective Services officials and a prosecutor assigned to the case, urging them to restrict Carter’s access to her children even more, blocking her from seeing them altogether, but state authorities refused.

“My request was for a change in supervision to a no contact order which I was informed could not be granted,” Woods wrote.

Woods then tried another strategy to block Carter from seeing her children. The doctor brought her concern directly to Andy, while Ellie was still hospitalized. Woods told him that she had video proof of his wife committing a crime, though she declined to elaborate or show it to him, Andy said in an interview.

Then she told him that the hospital wouldn’t discharge his daughter into his care unless he obtained a restraining order against his wife, blocking Carter from seeing her children, Andy said.

The doctor told him the court order requested by Child Protective Services wasn’t good enough, and that his wife was dangerous, Andy recalled. Woods told him that, even while supervised, Carter could hurt Ellie with a doctored glass of water or piece of candy, Woods wrote in her notes describing the conversation.

Andy said he had a brief moment of doubt when Woods told him she had video of Carter harming Ellie, but until he saw evidence, he wasn’t going to turn on his wife.

“Until you show me proof,” Andy remembers telling Woods, “I’m going to go with the order the judge came up with.”

Woods’ focus on child abuse

Woods started at Mary Bridge only a few months before reporting Carter to Child Protective Services. She was hired to serve as the medical director of the hospital’s child abuse intervention team in late 2017 after more than a decade in the Army, according to her résumé.

Woods testified in Carter’s case that she became interested in child abuse prevention while serving as a doctor in the military, and along the way, she said she became an expert through firsthand experience. She said she reviewed cases of suspected child abuse at multiple hospitals during her career, including at Madigan Army Medical Center, where she reports on her résumé that she founded the hospital’s child abuse team in 2016.

In order for physicians to become certified as experts in specific areas of medicine, such as performing surgery or treating cancer, they often must complete immersive, yearslong fellowship training at academic hospitals and pass board exams. But Woods testified that it was not essential for her to attend a child abuse fellowship program or pass a certification exam to become an expert in her field. Woods noted that she helps train those who are completing the child abuse fellowship at Seattle Children’s Hospital and is responsible for training medical residents at Mary Bridge “on all aspects of child abuse.”

Woods and Mary Bridge officials did not answer specific questions about her qualifications to teach child abuse fellows. Officials at Seattle Children’s, which manages the state’s child abuse medical consultation network, did not answer specific questions about Woods’ qualifications.

“We value the different nationally recognized paths in which experienced medical providers can gain expertise in caring for some of our state’s most vulnerable children,” a Seattle Children’s spokeswoman said in a statement. “We fully support the qualifications of our providers who are committed to improving the health and safety of children.”

The field of child abuse pediatrics was established more than a decade ago, part of a nationwide effort to improve and standardize the detection of child maltreatment and improve research on the subject. In 2009, when Woods was two years out of medical school and still completing her required residency program, the American Board of Pediatrics allowed doctors who’d already spent years working informally as child abuse consultants to take the certification exam, and if they passed, they were grandfathered in as board-certified child abuse pediatricians.

Any pediatrician wishing to specialize in child abuse since then has been required to complete a three-year fellowship, during which they receive instruction on the evolving — and sometimes disputed — science that doctors rely on to differentiate accidental injuries from those that are inflicted.

In a series of op-eds written in response to an NBC News and Houston Chronicle investigation into the work of child abuse pediatricians, leaders in the field have argued that skills learned during the three-year fellowship is what makes certified child abuse pediatricians more qualified than other physicians to assess children who may have been abused.

“During their training, fellows develop an understanding of the scientific evidence involving the biomechanics of childhood injuries and the physiologic and psychologic effects of trauma and neglect on a child,” Dr. Amy Gavril wrote in a January article published by the American Academy of Pediatrics. “This training allows [child abuse pediatricians] to diagnose abuse in a scientific manner. They are equipped to differentiate between accidental and inflicted injuries, and have knowledge of medical conditions that may mimic abuse.”

The training also prepares child abuse pediatricians to testify in court and offers guidance on what to say — and what not to say — in reports to child welfare workers.

But in her role as a child abuse medical consultant for Child Protective Services, Woods has made statements or recommendations that appear to go well beyond her role as a doctor, reporters found. In one 2018 case, Woods reported that two young parents didn’t display an appropriate emotional reaction when they learned that their baby had suffered several fractures, and she pointed to them as likely suspects. That goes against the guidance of leading child abuse pediatricians, who say their role is to identify abuse, but not who committed it.

“Both parents remain concerning to me as either could have been involved or either could be protecting the other parent,” Woods wrote in her report to Child Protective Services. “In addition, neither parent behaved in a protective manner when child first presented with injuries.”

In another case examined by reporters, from 2019, Woods reported to Child Protective Services and police that twin babies who’d suffered numerous fractures had to have been the victims of abuse. Woods told Bremerton police that the only other possible explanation for the babies’ injuries would have been “a motor vehicle collision,” though it’s not clear what the basis for that statement was. Based on her report, police charged the mother, Baylen Armendariz , with felony child abuse, and Child Protective Services took custody of the children.

Three outside medical experts reviewed the twins’ medical records on Armendariz’s behalf and concluded that their fractures were most likely the result of a mineral deficiency that can lead to weak bones and easy fractures, not abuse. But the children remain in state protective custody and in the care of their grandmother.

Armendariz pleaded not guilty to the criminal charges, and the case is expected to go to trial in the coming months.

Al-Agba, the pediatrician who clashed with Woods in 2018 over her claim that a child’s bruise was likely the result of abuse, said it was insulting and irrational for the state to give more credence to the opinion of a doctor with fewer years of clinical experience and no fellowship training in abuse.

After reviewing the same photos that Woods relied on to determine that someone had hit the 2-year-old child, a police detective agreed with Al-Agba, writing that “the bruising appears to be very inconsistent, almost impossible to be hand, finger, fingertip marks.” The officer added, in reference to Woods’ report, “it is a little difficult for me to understand what the medical professionals are talking about.”

Notes from the Child Protective Services worker assigned to the case indicate that Woods reported having 14 years of experience related to child abuse, and the agency cited that in its decision to formally classify the child’s injuries as inflicted. Fourteen years earlier, Woods would have been in her second year of medical school, according to her résumé.

But when Al-Agba questioned that claim and raised concerns about Woods’ lack of fellowship training with officials at both Mary Bridge and Child Protective Services, she says they brushed her aside.

“If I ask, ‘Does this person have abuse training, or does this person have extensive abuse experience?’ I think that's an important question,” she said. “I don't think that makes me a quack.”

In an interview Thursday, Ross Hunter, secretary of the Washington Department of Children, Youth, and Families, said Child Protective Services relies on Seattle Children’s to vet the expertise of doctors hired across the state to review cases of suspected child abuse. The agency does not review the qualifications of individual doctors or measure the quality or accuracy of their reports, Hunter said.

But based on some of the findings reported by KING 5 and NBC News, he said he wants to take a closer look.

“I can't tell you whether the fellowship training that you get to have a particular tag on your diploma actually matters in terms of the accuracy of the outcomes,” Hunter said, then added, “You've raised my interest in looking at how we do that particular contract.”

‘She should be held to a higher standard’

After Carter had been apart from her children for a year, with limited supervised visits and frequent video chats, her custody case went to trial in King County Juvenile Court last April. Judge Susan Amini presided over the proceeding, which included 15 days of testimony and arguments.

The Carters spent more than $300,000, much of it borrowed from family, to fight the case. Woods was the state’s star witness.

Over the course of four days, Woods testified that she believed “all of Ellie’s medical issues” were the result of medical abuse, even though the child was born severely premature and continued to require significant medical care after she was separated from her mother.

Woods claimed that only Carter had ever witnessed Ellie suffer seizures and that the child had since been weaned from anti-seizure medicine, though medical records showed otherwise. Multiple members of the hospital’s medical staff reported observing seizures, which was why Ellie was still receiving anti-seizure medication at the time of trial.

Woods testified that when she reported concerns that Carter had used Ellie’s health problems for her own gain, that “was related to a relationship with the Seahawks that was deemed inappropriate by hospital staff.” But a review of messages and social media postings show that it was members of the hospital’s marketing team who invited an NFL player to visit Ellie in the hospital and promoted the event to the media.

And Woods testified that soon after Carter was removed from the hospital by police, Ellie “wolfed down” a McDonald’s Happy Meal, though she later acknowledged during cross examination that she did not witness the event and could not say who had. Other members of the Mary Bridge medical staff testified that they did not believe Ellie would have eaten a whole Happy Meal, as she continued to have difficulty eating in the months after she was removed from Carter’s care.

As for the video that Woods said was proof that Carter was abusing Ellie? Woods testified that the footage showed Carter secretly dumping medication from a syringe after pretending to administer it. The medicine was intended to prevent dangerous blood clots. But when lawyers played the video for other witnesses, including a doctor who supervised Ellie’s care, they said it showed no such thing. Plus, two hospital staff members were in the room at the time and did not report wrongdoing, Amini, the judge, later noted.

With each statement by Woods, Carter said she fought the urge to shout out in court.

“I think just as a doctor, she should be held to a higher standard,” Carter said in a recent interview. “People should be able to expect that she tell the truth. And she just didn't.”

The judge agreed. More than three weeks after the trial ended, she issued her order. In a scathing 26-page report, Amini both dismissed the state’s case against Carter and rebuked the doctor who’d initiated it. Most of Woods’ testimony, the judge wrote, was “without supporting factual basis.” Amini dismissed parts of Woods’ conclusions as “not plausible” and “speculation at best.”

Carter was video chatting with her husband and children while they ate dinner — even during the separation, she always wanted to eat as a family — when her lawyer texted her on June 24.

“We f------ won,” he wrote.

Carter looked up from her phone and screamed. Tears streamed down her cheeks as she shared the news. Spencer stood up from the table and asked if they could come home that night. Ellie ran to her room and started packing her toys.

The next day, for the first time in more than a year, Carter was allowed to pick up her children from school.

She felt like the cloud of suspicion that had followed her for 14 months was finally lifting. Yet, she and her family have struggled to move on.

Ellie, now 6, talks frequently about the time she was forced to spend away from her mother, a period she refers to as “the rules.”

“Well, do you want to know what the rules did when I was in the hospital?” Ellie said one evening last month. “They wouldn't let my mom visit me. They wouldn't let my mom visit me. Even though she was my mom.”

Carter tries to comfort and reassure her, but she, too, lives in constant fear.

“We're just much more fearful than we ever were before,” she said in January. “I think one of the main things that I experience is that if somebody rings our doorbell, I'm scared to answer it, because I don't know if it's going to be somebody coming with more allegations and trying to take my kids away.”

‘I’m scared’

Two weeks later, on the evening of Feb. 6, Carter’s doorbell rang. Their home security system recorded video and audio of what followed.

A Child Protective Services worker and a police officer waited on the porch.

Andy, who saw what was happening through an app on his phone, jumped in his car and sped home from work. Carter stepped out to meet the officer and the worker while Spencer, now 10, curled up in a corner and repeatedly texted her from his tablet: “What is wrong? … I’m scared … Is it OK? … Mommy?”

The child welfare worker explained that the agency had received two new reports from members of the child abuse intervention team at Mary Bridge Children’s Hospital. Although nobody at the hospital had seen or treated Ellie in more than six months, the hospital staff members were reporting — without evidence — that Carter had begun giving her daughter oxygen treatments that she does not need.

Medical and billing records show that Ellie hasn’t received oxygen treatments in more than a year. Mary Bridge officials did not answer questions from reporters about what prompted the latest reports or who made them.

One of the referrals came from a pediatrician on the hospital’s child abuse team, the Child Protective Services worker said. She would not name the doctor, but Woods is the only physician who matches that description.

The reporting pediatrician wasn’t just concerned about unneeded oxygen treatments, the Child Protective Services worker said. The doctor also reported to CPS that “there’s a long history of medical child abuse,” the social worker said, reading from the report. The doctor reported that “the child is very healthy when not in the mother’s care.” And the doctor reported that Ellie “needs to be hospitalized as soon as possible,” with directions to bring her to Mary Bridge for evaluation.

Carter refused and showed them the dismissal paperwork. After about an hour, the CPS worker and the officer left without taking any action. But Carter and her husband fear they’ll be back.

That evening last week, Andy Carter got on the phone with their lawyer. He had decided that it was time to take out a restraining order — not against his wife, but against Dr. Elizabeth Woods.

Taylor Mirfendereski is an investigative reporter for KING 5 in Seattle.

Mike Hixenbaugh is a national investigative reporter for NBC News, based in Houston.