Residents of Seattle enjoy some of the most affordable electricity in the country, but the city-owned utility that generates that power is accused of harnessing cost-effective electricity on the backs of Puget Sound salmon, killer whales and the way of life for Native American tribes in the Skagit Valley, a KING 5 investigation found.

“The [city of Seattle has] taken a lot from this tribe for the last 100 years, and the tribe is not going to take it anymore," said Scott Schuyler, natural resources director of the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe, based in Sedro-Woolley. "The status quo is not working, and we will not allow it to continue."

The Skagit River is, without question, one of the marvels of the Pacific Northwest. Stretching 150 miles from British Columbia through the North Cascades and emptying into the Salish Sea in Mount Vernon in Skagit County, it’s the largest river in western Washington. It’s the only river that’s home to all five species of Puget Sound salmon. It’s the most important food source for the beloved orca, and the Skagit River is the “soul” of the people who inhabited the lands around it for centuries before the first Europeans arrived.

“Our people have resided in the Upper Skagit Valley for literally 10,000 years now," said Schuyler. “The Skagit River is the lifeblood of my people. The salmon are also part of that lifeblood.”

Nearly a century ago, a major change came to the wild, free-flowing, undeveloped Skagit River: the industrial revolution.

In 1918, Seattle City Light began construction on three massive dams in the middle of the river, in Whatcom County, for hydropower. The utility built Gorge Dam first near Newhalem. Above that, Diablo Dam came next, followed by Ross Dam, completed in 1949. All three dams are located in what is now designated within the North Cascades National Park.

Since that time, Seattle residents and businesses receive roughly 20% of their power from the Skagit River at a bargain price. Compared with the most populous 25 U.S. cities in 2012, Seattle offered the cheapest power of all. The latest data available from the Edison Electrical Institute shows Seattle’s prices aren’t in the top spot, but City Light customers currently pay less than half of what residents do in cities such as San Diego, New York and Boston.

Power generated on the Skagit is also considered a clean fuel source because unlike energy derived from coal or natural gas, hydroelectric operations don’t burn fossil fuels. That means hydropower doesn’t create air pollution. Water is also a free, renewable resource. Seattle City Light was the first utility in the nation to achieve carbon-neutral operations and the Skagit Project was the first hydroelectric facility in the country to be certified as a low impact hydropower project by the Low Impact Hydropower Institute.

In addition to cost-effective, “green” power, damming the Skagit has created abundant recreational opportunities. The dams replaced free-flowing sections of the river with three beautiful reservoirs enjoyed by boaters, hikers, campers and fishers. According to the National Park Service, in 2019, more than 1 million tourists visited Diablo and Ross lakes – lakes created by Seattle City Light.

But in a 3-month investigation involving dozens of interviews and a review of more than 1,000 pages of government documents, the KING 5 Investigators found there’s a dark side to generating light from the Skagit River.

The utility denies it’s to blame, but since the federal government last relicensed Seattle’s Skagit River Hydroelectric Project in 1995, three species of fish that inhabit the river have landed on the endangered species list, as per the Endangered Species Act: bull trout, steelhead and Chinook salmon. And in 2005, Southern Resident orcas, who depend on Chinook salmon from the Skagit to survive, were also listed as endangered.

“Salmon are in trouble,” said Ed Eleazer, regional fish program manager for the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife. “Millions, if not billions of dollars have been spent trying to recover Chinook salmon, but they continue to decline. [When a species ends up on the endangered species list] it means we’re trying to protect them from extinction.”

Government and tribal scientists agree many factors contribute to the decline in the health of the Skagit River’s fish runs: climate change, warming ocean temperatures, development and industry, including farming.

At issue is whether Seattle’s hydropower project is part of the problem.

It’s well documented by federal agencies that dams hurt fish by blocking off upstream habitat they need to spawn and grow. Dams also starve the river of sediment and other nutrients necessary for healthy downstream habitat. Seattle’s dams choke off nearly 40% of the river.

Tribes and federal agencies believe opening the habitat behind Seattle’s dams could be key to Skagit salmon recovery. This could be achieved by dam removal or building a system to move fish past the dams, such as a fish ladder.

Seattle City Light’s project does not include any infrastructure to help fish get over their dams and access 60 additional miles of habitat. And so far, City Light officials are refusing to agree to undertake a comprehensive fish passage study to ascertain if the utility needs to provide mitigation measures to help fish access blocked off habitat. A fish passage study encompassing the entire dam operation has been requested by many agencies, including the Upper Skagit Tribe.

“We’re not trying to blame everything on [Seattle City Light]," said Jon-Paul Shannahan, managing biologist for the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe. "That wouldn’t make sense. We’re asking them to come to the table to identify their own impacts and help us fix it."

In public messages about the Skagit dams, City Light says the utility is helping, not hurting fish. They label themselves “the nation’s greenest utility,” “environmental stewards to mother nature,” and say their way of doing business mitigates the negative impacts caused by their hydropower project. According to its website: “That means inexpensive hydroelectricity for you, and a healthy salmon population for the Skagit.”

“We operate our hydro projects in a fish-first manner. That’s important to us,” said Debra Smith, CEO and general manager of Seattle City Light.

Seattle’s management of its dams is of special concern right now because its license for the Skagit River Project, ultimately issued by the U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), will expire in 2025. Discussions are underway between the city, tribes and regulators to try to come to an agreement on what conditions will be contained in the new license, which could last for 50 years.

In public records submitted for the relicensing process, government stakeholders accuse the city of failing to accept its responsibility for declining fish populations. They also said City Light representatives are not engaging cooperatively. One government representative said utility officials are engaging in “arrogant” behavior by “summarily disregarding” the input of state and federal scientists with decades of experience.

“[This is] not a collaborative process,” wrote scientists for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA Fisheries), an arm of the U.S. Department of Commerce.

“[Seattle’s attitude means we] never achieved the collaborative nature [in license discussions] as was the intention described to the Tribe,” wrote scientists from the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe.

In documents submitted to the FERC, government and tribal leaders requested that Seattle study a host of issues to best understand the project’s impacts before conditions are set for the next license. But of primary concern, according to public records, is the issue of fish passage.

The city of Seattle, for decades, has held the position that their dams aren’t harmful to salmon because fish never swam in the upper portions of the Skagit River, even before their dams went in. That means their dams are located in a perfect spot - where salmon could not historically access due to nature-made obstacles such as steep canyons and massive boulders.

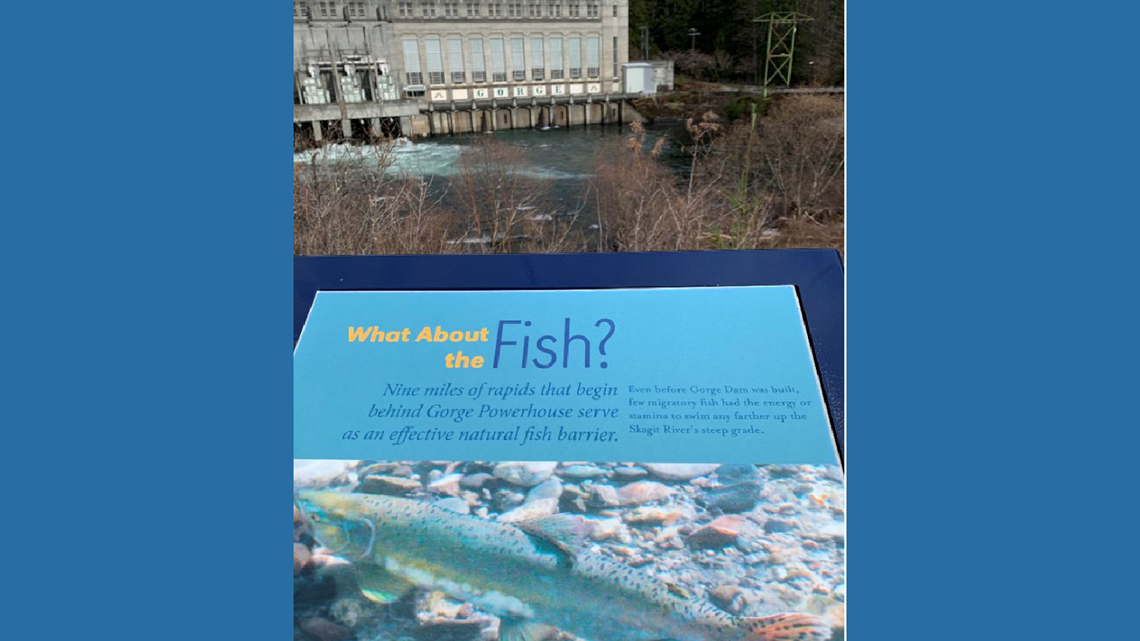

In the town of Newhalem, where the hydropower project begins, tourists are greeted by signage where Seattle City Light explains the unique physical features and geological structures that kept fish out of the area.

“Nine miles of rapids that begin behind Gorge Powerhouse [in Newhalem] serve as an effective natural fish barrier,” wrote City Light in the signage. “Even before Gorge Dam was built, few migratory fish had the energy or stamina to swim any farther up the Skagit River’s steep grade.”

The Upper Skagit’s top biologist said this is a “false narrative.”

“It’s kind of like big tobacco when they used to say ‘smoking’s not bad for you,’" said Shannahan. "This is big hydro saying: ‘fish never got up there.’ It’s the Pacific Northwest. Fish swim upstream. That’s what they do. There is no insurmountable barrier to salmon here."

It’s not just the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe demanding a comprehensive fish passage study. Public records show every tribe, regulatory agency and non-profit organization involved in the relicensing process disagrees with City Light’s position. Here is a list of the other agencies requesting a comprehensive fish passage study:

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- NOAA Fisheries

- Swinomish Indian Tribe

- Salk-Siuattle Indian Tribe

- Washington State Dept. of Fish and Wildlife

- National Park Service

- National Forest Service

- Washington State Dept. of Ecology

- Bureau of Indian Affairs

- Board of Skagit County Commissioners

- American Rivers and Trout Unlimited

- National Parks Conservation Association

Smith, of Seattle City Light, said their scientists have no indication that salmon ever made it past the first damn, but that the utility is willing to remain flexible.

“I absolutely believe that Seattle City Light and the city of Seattle have had a commitment to follow the science," said Smith. "We believe, our position continues to be we have not seen evidence of fish in that reach above Diablo Dam. [But] we need to listen more, and we are starting that process, and that’s what we’re doing. We’re listening and we’re going to approach the discussion with a completely open mind.”

Smith also said it’s important to remember that the licensing process has a long way to go and no final decisions have been made.

The utility has until April 7 to submit its Revised Study Plan to the FERC, the federal agency charged with licensing hydropower projects.

“Count on me to be fair, to listen,” said Smith. “The thing I want folks to know is, my heart’s in the right place. And my team, they understand that. And my job is to set the tone at the top. That means accountability, transparency, intentionality. That’s the way I want to continue to engage with all the license participants, but in particular, the sovereign tribes that we work with and whose yards we live in.”

The Upper Skagit Indian Tribe said with their sacred salmon sliding toward extinction, the soul of their culture is at stake, and they won’t stop fighting for it until they get their river back.

“The Skagit helped build Seattle into probably the greatest city on the West Coast and we have an expectation now that that’s returned to the Skagit," said Schuyler. “The Skagit is in desperate need of help right now and we’re hoping [Seattle] city government now sees fit to start helping us rebuild the Skagit to the greatest river in the Puget Sound.”