Five years after the deadliest landslide in U.S. history devastated Oso, officials are working to map landslide susceptibility across Washington to better understand how these kinds of slides work.

Deep-seated slide study

The Department of Natural Resources has asked the state legislature for $2.9 million in funding to study deep-seated landslides, like Oso, which killed 43 people and destroyed 49 homes and structures. Deep-seated slides are rooted in bedrock rather than soil like a shallow landslide.

“That’s something we really want to sort of hammer up, because no one has really spent the time to study the landslide of that area in detail, and that’s really important,” said Stephen Slaughter, DNR landslide hazards program manager.

Funding would allow two geologists to drill boreholes into 50 square miles along the State Route 530 corridor near Oso to explore deep-underground landslide mechanisms. The research can hopefully be applied to 18 other counties in northern Washington, including King, Pierce, and Snohomish, that have similar geology. It could also help residents better understand the potential of a slide on their own land.

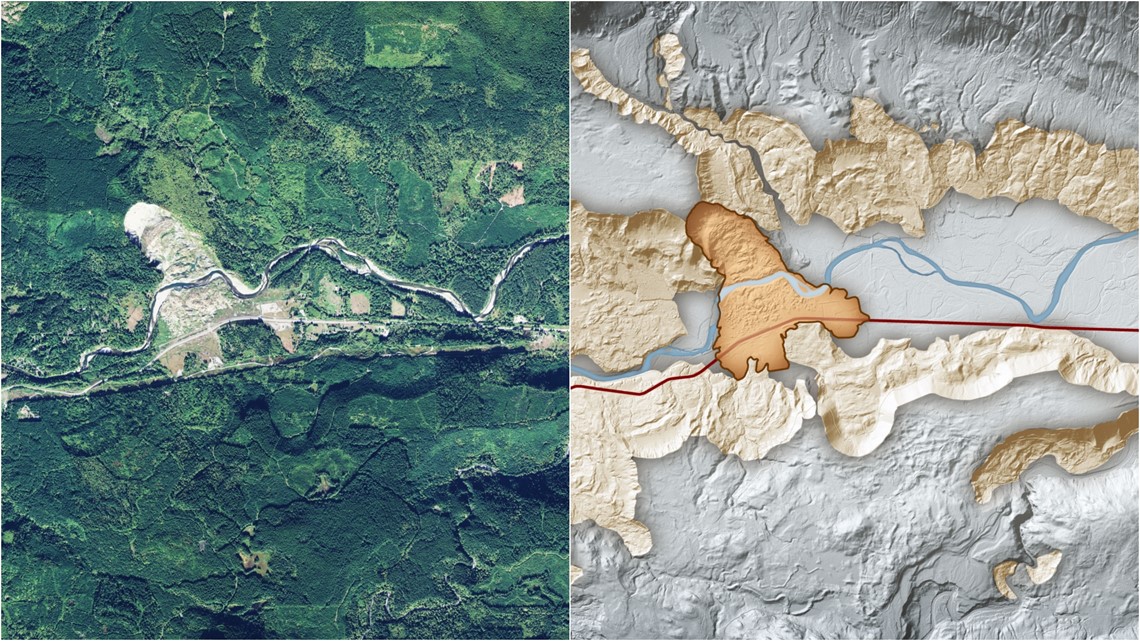

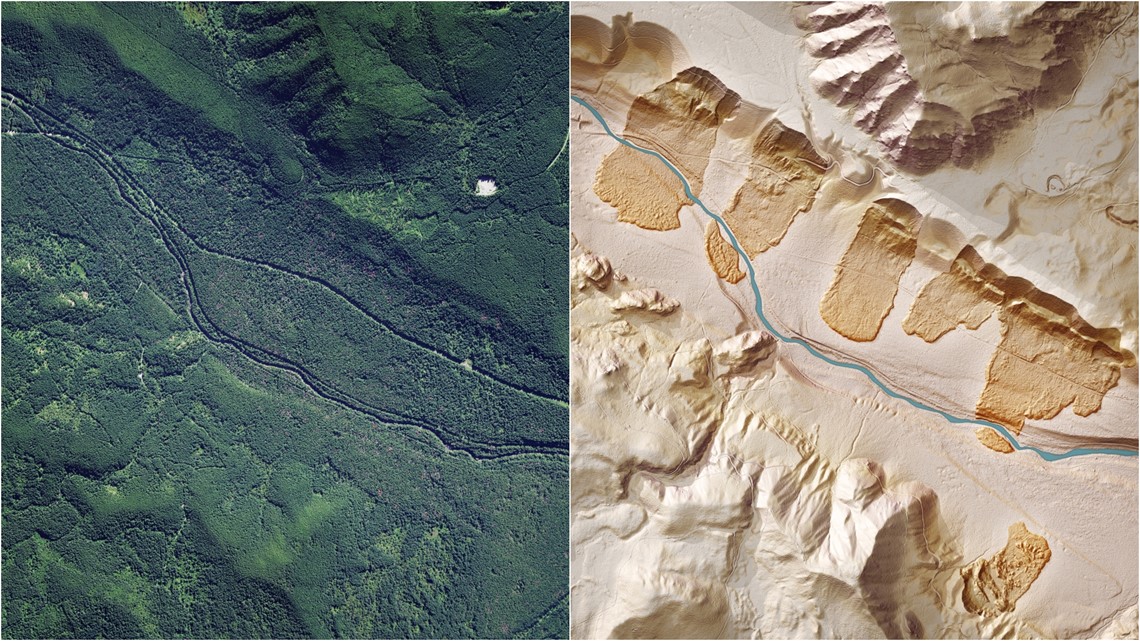

Lidar slide mapping

Meanwhile, DNR geologists have mapped other areas of Washington state since the Oso landslide using laser technology called lidar, which measures topography and landslides in a way you can’t see with other surface features, like trees, in the way.

Although lidar is not necessarily new technology, Slaughter says it is getting less expensive, making it a more viable option to map the entire state. So far, the department mapped Pierce County in 2017, the Columbia River Gorge in 2018, and just finished mapped the western half of King County in January. Whatcom County is on tap with data expected to be published this summer.

Mapping in King County found high landslide density along the Puget Sound bluffs, river corridors, and in upland areas of the Cascades. It also found that just 10 percent of the Puget Sound shoreline was under landslide risk compared to earlier mapping that showed about half of the shoreline at risk.

“There were a lot of false positives,” Slaughter said. “We took those out, because we have better data now to see it more precisely and accurately.”

Slaughter says we’re between six and 20 years out from having a lidar map of the entire state.

Prepare for a slide

Homeowners can access the maps on DNR’s geology portal to determine how susceptible their property is to landslides. The presence of a previous landslide in the area is one of the biggest risk factors, according to DNR.

Once you know whether your home or workplace is at risk, make a disaster preparedness plan with your family.

Know the triggers for landslides, such as erosion beneath a cliff, earthquakes, oversaturation from heavy rainfall, or excavating at the base of slopes. Landslide warning signs include cracks in the soil or sidewalk, changes in surface drainage, and bulges in retaining walls or tilting of walls.

You can also take steps to mitigate landslide risk on your property by draining water away from slopes, planting native ground cover on slopes, and avoiding placing fill soil, yard waste, or debris on slopes.