Honoring the Buffalo | Following the makings of a traditional Indigenous feast

"It's that satisfaction of what your Elders have asked: How will you feed the people?" Mark Colson said.

Inside the Hunt It isn't just about taking down a buffalo - it's about honoring the animal's sacrifice.

On a foggy morning in Pend Oreille county, the sun slowly rises to reveal the unincorporated community of Usk, WA. Usk is right on the Idaho border and used to be a logging hub, but it is now a quiet neighbor to the Kalispel tribal lands. It’s the kind of small community where it’s big enough to have its own post office and general store, but not much else outside of that intersection.

On Kalispel grounds, there are unexpected residents. A herd of buffalo—sacred symbols for the Indigenous—live there too. They’ve been roaming the area since 1974. Under the stewardship of the Kalispel tribe, the herd is at 150 strong now, but when they were first brought over from North Dakota, there were just 12.

The tribe works with other tribes to help supply buffalo for ceremonies and gatherings when needed.

That’s precisely what brought Mark Colson and his team to Usk. Colson, who is part Lakota, is in search of a certain cow—or female buffalo. They will take her home to prepare a feast for Indigenous People’s Day in Seattle.

While the group is on trucks rather than on horseback, using guns instead of spears and arrows, the harvest proves to be a bit tricky as the cow continues to hide in the herd. The group has to take her home specifically, as she’s been set aside by the Kalispel tribe for the occasion. Her elusiveness gives the group a feeling that maybe she knows they’re looking for her.

It’s hours of walking and stalking the buffalo, with several false starts. Colson draws his shotgun, only to put it down, over and over again. The harvest has become more of a hunt at this point.

Then, after hours, the moment reveals itself. There’s a clearing, and Colson has a clean line of sight to the buffalo. He shoots twice, and she comes crashing down.

Unlike what many might consider a traditional hunt, there are no high-fives or joyous celebrations at this one. The overwhelming emotion of the group is one of sorrow and deep gratitude.

Someone whispers a quiet, “good shot,” to Colson and they shake hands. Once they’ve confirmed the buffalo has passed, Colson kneels down beside her head and prays. His hands are full of the sacred gift of tobacco and he sprinkles it around her. He also lights a bundle of sage to smudge the buffalo, which is another ritual that purifies and dispels negative energy.

“We're just letting the spirit of the animal, asking it to go in a good way, we took it in a good way and honoring it,” Colson explained later.

When asked why it was so somber, Colson said it reminded him of his ancestors.

“All that it represents, you know, the whole thing, feeding the people, the ceremony the camaraderie, everything together is a wave of emotions,” he added.

The ceremony is quick as they don't have much time to process before bringing the cow back to Western Washington. They use a John Deere to pick up the buffalo from the field and take her to a shed in the heart of the ranch. There the group worked to drain, strip and part the buffalo. It’s hard work that takes multiple people and several hours—the chilly morning and the slippery tallow adding to the challenge as the team fought to keep their hands nimble and warm.

However, the mood has shifted now, with plenty of laughter to go around.

“We know what we’re eating, and we know where it came from, we’re putting all this love and laughter - all that medicine is going into the food right?” Colson said. “And so that’s what we’re going to feel when we eat it.”

Ixtli Whitehawk is watching the men work and taking pictures. Whitehawk is Colson’s partner and has been an organizer of Seattle’s Indigenous People’s Day celebration for the last ten years.

“The buffalo have a relationship with the people, and taking the shot is a commitment,” Whitehawk explained. “Each and every one of us that was present even though we didn't physically take the shot, we make a commitment and we make that honoring to that buffalo we thank it in our own way.”

Honoring the whole animal, as it has been done since time immemorial, means eating and using every part. The pelt and skull of the buffalo will be used in ceremony. The bones will be made into tools. Even what’s inside the buffalo doesn’t go to waste.

In the middle of our conversation, Colson approaches Whitehawk with a liver in his hands. “Everybody took a bite,” he said.

Whitehawk does too, and the sound of the raw liver crunching is startling, given that the liver looks so soft.

“It’s clean, if you think about how it’s raw meat, people get psyched out,” Whitehawk said. “But it’s really mild.”

Hailed as the most nutritious organ, Colson explained the liver was the people's choice to satiate hunger quickly after the hunt. He added different tribes have different philosophies about this, so traditions may vary.

The group divided the buffalo the best they could to make it portable back to western Washington. They will be taking it Skokomish, to Mark and Ixtli’s house, to finish processing.

Learning to Slice and Dice "Feeding the people - it's healing, it's spiritual work," Mark Colson said.

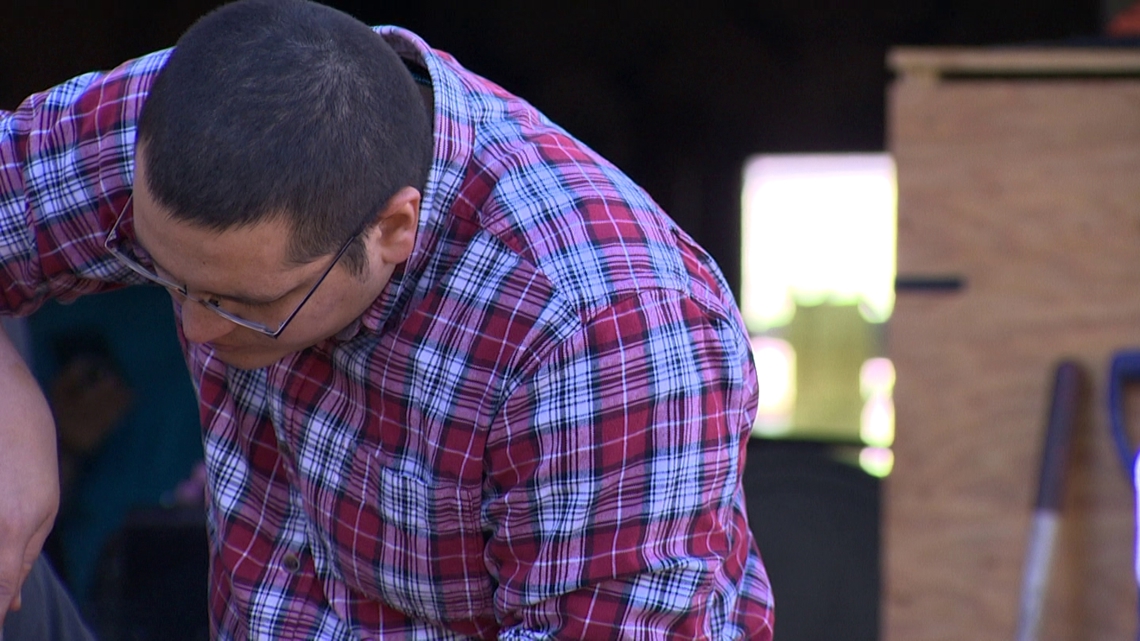

After having survived a whole day of driving, the very next day, Mark Colson was back to working on the buffalo. He had Ixtli’s 18-year-old helping him, as they had hundreds of pounds of meat to process.

Processing included identifying the meat, slicing, dicing, or fileting. Then it was divided into what kinds of food it will be made into for the big Indigenous People’s Day feast.

“It's just a cool feeling you know? It's that satisfaction of what your Elders have asked: how will you feed the people? Physically, metaphorically, so it's just satisfying,” Colson said.

This is also a passage of generational knowledge. Colson frequently gave out pointers on how best to hold the knife, and what size chunks of meat work best.

Everyone is welcome to the Indigenous People's Day celebration but Colson said he's particularly excited for the Native youth who don't get opportunities to connect to their roots in this kind of way.

“To show them we're still here, that they have a history, who they came from, all the tough times their ancestors went through to still be here,” Colson said. “Really encourage that 'Who are you? Where do you come from? What are you made out of?' so they can keep going for the next seven generations.”

It’s never easy work trying to feed hundreds, but Colson said it’s cool to see how one cow could feed so many people.

“To sit back and look at the whole community, having one buffalo as part of them now, it's pretty neat,” Colson said. “It's like feeding the people-- not just filling their tummy, repairing that DNA, it's healing, it's spiritual work taking place, happening on a day that we had to fight for to be recognized.”

Indigenous People's Day - but the Fed says 'No' Efforts to move away from a legacy of genocide and toward a celebration of Native tradition and identity.

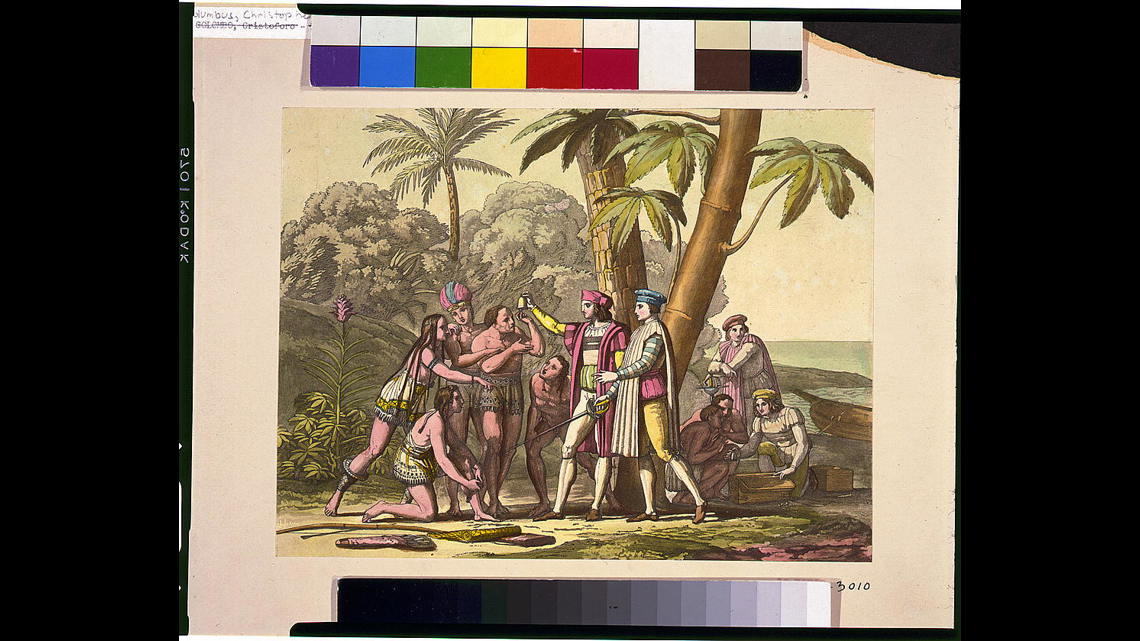

In 2020, as the world protested for social justice following the police murder of George Floyd, an old wound resurfaced: the legacy of Christopher Columbus.

Protesters vandalized monuments of colonizers and slave owners all over the nation. Columbus statues were not immune. Not especially after then-president Trump signed the annual Columbus Day proclamation saying “Sadly, in recent years, radical activists have sought to undermine Columbus’ legacy... and this June, I signed an executive order to ensure that any person or group destroying or vandalizing a Federal monument, memorial or statue is prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law.”

Since then, Columbus Day proclamations have changed in tone. The Biden administration’s Columbus Day proclamations focus on the heritage of Italian Americans, call Columbus’ voyage, “historic,” rather than “heroic,” and acknowledge the “painful history of wrongs and atrocities that many European explorers inflicted on Tribal Nations and Indigenous communities.”

Biden also became the first president in U.S. history to also issue an Indigenous People’s Day proclamation on the same day.

Christina Roberts, the faculty fellow at Seattle University’s Indigenous People’s Institute says she grew up learning about Columbus a certain way too.

“I'm sure many of us remember learning in 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue,” Roberts said.

Roberts is Nakoda and Aaniiih. She said correcting that wrongful interpretation of Columbus is the first step in healing.

“It's important to acknowledge that Columbus was not a hero,” she said. “He was somebody who was ambitious, who was driven, he had a desire to want to prove that he was capable person to return the favor of what occurred to allow him to have that opportunity. Some of the things that are not focused on are what happened after the fact.”

Roberts talked of genocide, rape and torture, that’s often not discussed in the history of Columbus.

“Thinking about the fact that hands were cut off, babies were murdered, women were raped,” she said. “There were so many horrific things that occurred during that intense time period that it was-- there were no consequences at that time at least for the people who were doing those things, and in fact they felt justified.”

To have a day to celebrate the very man who terrorized the Indigenous people of Turtle Island, the name they gave North America, Roberts said feels deeply hurtful.

“I cannot represent all Indigenous perspectives but when I think about it myself, it's just incredibly painful,” Roberts said. “It's almost as if it becomes a day of mourning, day of recognizing all that has occurred in the past.”

To be clear, Roberts said she’s not suggesting “revisionist history” like the Trump administration’s proclamation accused people of doing.

“There is a part of me that also recognizes we can’t erase the past,” she said. “We cannot move away from things that make us uncomfortable. And yes, I would love to see a time and a space where there wasn’t a day set aside to celebrate an individual like Christopher Columbus, but at the same time, I would not want to erase his influence, I wouldn't want people to be ignorant about what occurred during that time period.”

However, many states, cities and municipalities have already moved towards observing Indigenous People's Day in lieu of Columbus Day.

Seattle officially recognized the day ten years ago, after the city council passed an ordinance. Since then, every 2nd Monday of October has been Indigenous People's Day.

According to Pew Research, only 16 states and American Samoa still observe Columbus Day exclusively.

Roberts said the tide of change proves the resiliency of the Indigenous community.

“To push for a day of celebration, to push for a day of recognition, to have it correspond with a day that once represented so much pain is something that I feel is a part of the ongoing healing that we all need as we move forward because we're stronger together,” she said.

Seattle's Indigenous People's Day In the kitchen, laughter, prayers and joy are put into the food.

In a matter of three days, the buffalo has been hunted, processed and cooked for the Indigenous People’s Day feast. The feast is a highlight of course, but the day isn’t just about the meal. It’s about preserving a vital tradition and celebrating cultural heritage.

Like any major celebration, the preparation work began long before the first guest stepped foot inside Washington Hall. And like with any good feast, the day’s meal also included plenty of carbs.

“We’re making buckskin bread,” Marcella Johns said, as she kneaded flour and water together. Johns and her spiritual sister Diona said the hard shell and soft insides of the bread made it ideal to mop up the buffalo stew.

Johns who is Skokomish, is an Indigenous Foods caterer. So that morning in the kitchen at Washington Hall, she was calm about feeding hundreds of people.

“I started cooking with my grandma when I was little, she says that your mood and your prayers and everything that you have while you're in the kitchen is like in the food,” Johns said. “We've been laughing, all day, so I'm hoping that as people are out there eating the food, they're happy and feeling good and just want to laugh.”

Everything Johns and Diona made was traditional. They had stuffed pumpkins with wild rice and chunks of buffalo meat. Wojape, a kind of fruit spread, as well as the highlight—the buffalo stew.

The stew is something Colson had made that morning and it was simmering in a giant copper pot. Johns gave the stew a stir. “Looks like he's got corn, green beans, ground buffalo, potatoes, carrots and onions.”

Johns said there’s a reason why people call food, medicine.

“Doing traditional foods, going out and gathering, and preserving and preparing, it just kind of makes you more in tune with what you're serving, and it's healthier,” she said.

It was around five o’clock that people started trickling in, perhaps following their noses. Within the next half hour, Washington Hall was filled with people, with the food line snaking around the entire room.

As people made their way through, their plates ended up being piled on with delicious food. Raven and Olivia Ford were one group.

“I was exhausted because of the full day of events and I almost didn't come, but I was like ooh, they're going to have the good bison,” Olivia said.

She said she knew Indigenous people would cook and serve bison the correct way.

“I'm a chef, so I just feel like it's really important to know where your stuff comes from, and know that it's like fresh, hasn't been sitting around, hasn't been through like a bajillion people's hands, and on a bajillion different tables,” she said.

Joseph and Aza Barnhart also saw the appeal of a good buffalo meal. Their reviews of the food were high.

“It's juicy, I've had it before and I'm familiar with it, and if I could eat it more than I could eat beef for instance, I'd definitely do that,” Joseph said.

More importantly to Barnhart though, is the gathering of people itself. He said it was something he wanted his young daughter to witness.

“The chief wasn't about who had the most money, it was about who had the most respect in the tribe, the people they trusted the most,” Joseph said. “When they put on events like this, it shows that trust in the community. People feel safe, people feel wanted, and they're able to be themselves, and to reconnect with family and make new friends as well.”

Olivia, who is a member of the Nisqually tribe said she won't let her daughter Raven grow up in the dark about her culture and history.

“When I was growing up it was Columbus Day, and we learned about Christopher Columbus and his boats and drew little pictures and like-- that was a craft we made,” Olivia said. “It's so whack.”

“For me, I wasn't raised like knowing a lot of my Indigenous culture so I just want her to know it as she is growing up and not be ashamed of it,” Olivia continued. “And like she's super excited to see the dancers which is why we're just sitting here.”

After dinner, the programming started, with song and drumming. It also included a celebration and deep discussions on stage.

Millie Kennedy, who was instrumental in passing Seattle’s Indigenous People’s Day recognition ordinance explained the work that went into reclaiming the day.

“The City of Seattle became the second major city in the United States to pass an Indigenous People’s Day resolution,” Kennedy said. “That’s not all—the City of Seattle is the first major city to make Indigenous People’s Day a holiday that was on Monday, October 13th, 2014.”

And finally, Ixtli-- having gone through a full day of events briefly took the stage with a reminder.

“We have families that we are born into but when we build intentional kinships we walk with responsibility and we walk with accountability, especially for our young people,” she said. “For our little ones that are coming onto this world, that are learning as we walk here, in ways we are sharing, this way of being.”

“I think that there's a good movement going on, different states, different cities, they're all starting to adopt Indigenous Peoples’ Day as a holiday in their own right,” Joseph Barnhart added. “I think that trend is just going to keep growing, so we're going to have a majority of states wanting to recognize it to help push the federal government to make it a national holiday.”

At least in Seattle, resiliency and the adaptation of tradition has become something to look forward to every year.

“Indigenous people are still here, like there is a ton of us, and yeah, we matter,” Olivia added.

“Here we are in 2024, on a ranch in another reservation, taking a buffalo to feed urban Indians, so it is deep,” Mark Colson said. “When you think about it, our prayers are answered. We are living our prayers and living the prayers of the ones that prayed for us years ago—we’re still doing this, we’re here.”

Special thanks to the Kalispel tribe for their hospitality. We also extend deep gratitude to the Skokomish tribe and the Daybreak Star Indian Cultural Center, for providing us a culturally-sensitive and visually stunning background for this KING 5 Special.