LUMMI NATION, Wash. — The waters around the Lummi reservation have stood the test of time.

The water has seen the trials of the Lummi people.

“I've lost four family members in the last few years of life to fentanyl,” said Joe Morris, who has lived on the Lummi reservation most of his life.

Fentanyl took the life of Morris' brother, Lindy.

“The water was his oyster," Morris said. "He loved fishing and he always tried to be out on the water."

Lindy’s love of water was strong, but his addiction to fentanyl was stronger.

“We had a really good relationship until he got into his addiction,” Morris said.

Fentanyl is highly addictive. It is 50 times more potent than heroin. It is cheap, it is easy to buy, and it is tearing the Lummi Tribe apart.

There is evidence of the crisis all across the town, with posters put up by the Lummi Youth Council spreading awareness of the crisis and offering words of hope.

Four Lummi tribal members died of fentanyl overdoses in one week in September. Morris' brother, Lindy, was one of those four. He had just gotten out of jail.

“He got out Aug. 29 and was dead by Sept. 16 or 17,” Morris said.

Morris knows recovery is hard.

“You know, I used to be part of the problem," Morris said. "You know, I was a drug dealer. I lived as a drug dealer. I went to prison in ’09."

Morris was a cocaine dealer. He said he got life-changing help from God.

“It'll be 15 years this Christmas,” Morris said.

Now he works as a peer counselor with Lummi Counseling Services.

“I just help them get over their hurdles in their recovery,” Morris said.

The crisis is so profound that the Lummi opened a treatment facility this spring, the New Life Center, dedicated to opioid addiction.

Deanna Point, who is Morris' wife, is the Interim Director of the program.

“We used to be shocked when there was an overdose and now it feels like it's just like, 'Oh, there's another overdose,'" Point said. “Like, it's almost becoming normal for us just to talk about it. Like it's, you know, it happens out here much.”

The New Life Center has seven beds and is a place people can go to get help with withdrawals. Having resources on the reservation is what they said makes all the difference. Adding not only therapy and medication but also culture to the recovery process.

“You need that to heal, you need that to be whole,” Point said.

The center has a culture teacher and a culture room where people can reconnect with their heritage.

“Whether you're picking up that weaving tool right there or whether you're just sitting here meditating, whether you're just sitting here working on a project and learning, you know, this is what our ancestors did,” Point said.

Point knows this is important, she said culture, and this culture room, saved her life.

“I lost my daughter to spinal meningitis and that was the perfect way for me not to have to cope with that loss, and so that's when I fell into that cycle of addiction,” Point said.

Point’s parents were alcoholics and she was addicted to oxycontin for more than 13 years.

“This program right here is what saved my life, my culture saved my life, my children saved my life,” Point said.

The pull of fentanyl is so strong that it has torn some people away from their families and away from their homes. Dozens of Lummi are now living just outside of the reservation, in an encampment for the homeless.

“We do have at least 40 community members that are living in that homeless encampment,” Point said. “That right there shows you the power of fentanyl, because we've never had our people actually leave the reservation and go be homeless to feed their habit or addiction.”

The camp is now referred to as “Little Lummi.” Recovery coaches from Lummi Counseling Services go to the camp each week to do outreach. Point’s team said there are 4-8 overdoses in the encampment every single day. The people who live at the camp use Narcan to revive each other.

Lummi tribal member Jade Ridley was at the camp when an outreach worker asked if she wanted help at the New Life Center.

“It was kind of not really a question,” Ridley said. “I had been hearing good things about it, so I took my opportunity and came.”

After a 10-year fentanyl addiction, she took the step for herself, and for her 13-year-old child. The day we talked to her she said she’d been sober for a week.

“It’s exhausting being out on the streets, and I just want my life back, I want my daughter back,” Ridley said.

Ridley said getting over the withdrawals was hard, but the New Life Center made it easier.

“Everyone here is really hopeful and supportive, and I feel really thankful," Ridley said. "They made it a lot easier. They made me feel pretty good here, you know, they kept me stable, it was a lot better than expected."

Ridley’s father died of a fentanyl overdose last year. She said he died just two days after graduating from treatment. But Ridley said she has family support, like from her uncle who was one of the first people to ever be treated at the New Life Center.

“My uncle, his younger brother, was the first to go through this place," Ridley said. "And he's been encouraging. He's been clean for twelve weeks."

Earlier this month the tribe took their crisis from Washington state to Washington D.C.

“These impacts of fentanyl and opioids have been very drastic and very overwhelming,” said Tony Hillaire, the Chairman for the Lummi Tribe, as he spoke to a Senate Committee.

The Lummi chairman urged congressional leaders to declare the fentanyl epidemic a national emergency. He said more federal resources need to be available and that different tribes should not have to compete for grants to help their people. He said more law enforcement and recovery resources are needed.

“There are so many different pieces to this, but if we start with the highest level possible that the United States of America declares this a national emergency, I believe that we can overcome a lot of the barriers we are facing,” said Chairman Hillaire to the Senate Committee.

Hillaire told the Senate Committee the tribe is looking to build a permanent detox center because the New Life Center is frequently full. He said they have already gathered $15 million in funding, but still need $12 million more.

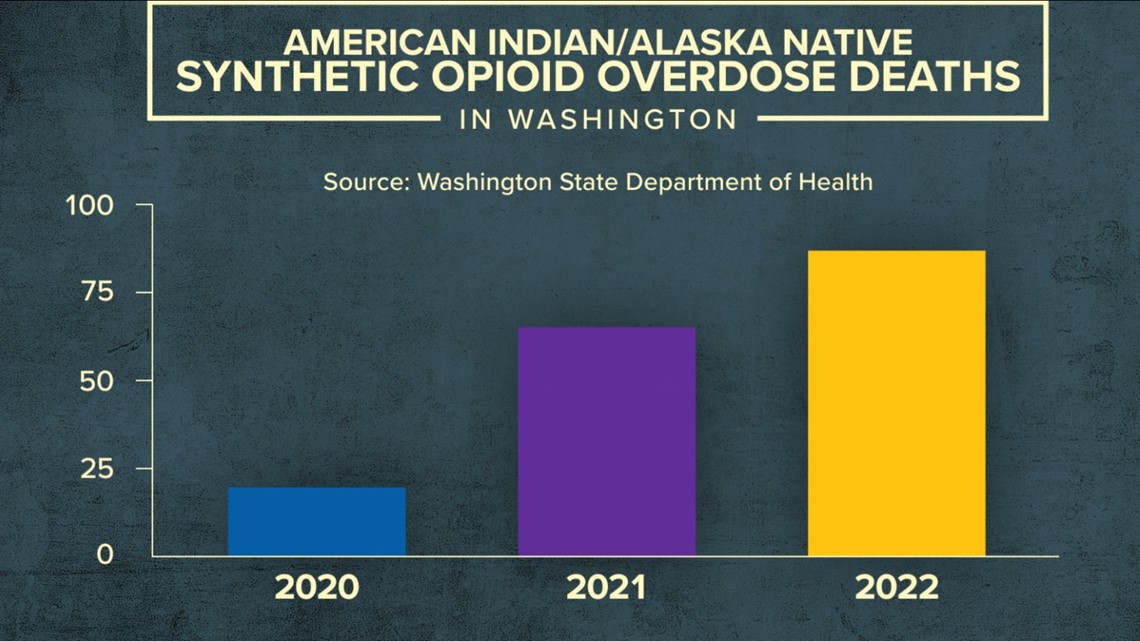

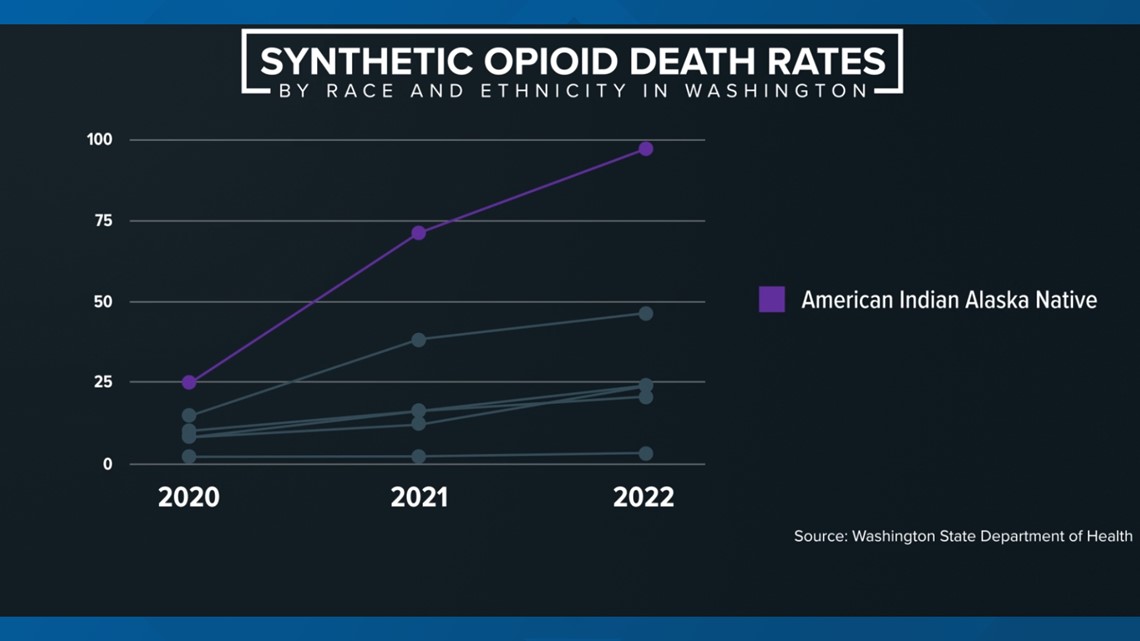

Across the state of Washington, synthetic opioid deaths have been increasing and it is seen very clearly when looking at the overdose deaths among American Indian/Alaska Native people in the state. According to the Washington State Department of Health, there were 24 deaths in this group due to synthetic opioids in 2020. That number was nearly four times higher (92 deaths) in 2022.

In the state of Washington, American Indian/Alaska Native people are being impacted the worst of any ethnicity or race by the fentanyl crisis, with a disproportionately high number of deaths.

To fully understand this crisis, you have to go back in time to the historical and generational trauma Indigenous people have endured.

“You're healing from, they used to say, seven generations back, when we lost our culture and lost our language,” said Rosalie Scott, the current director of Lummi Counseling Services.

Scott has lived on the reservation for 80 years and has worked in recovery services for 50 years.

“I think there were about 600 people back in the day when I was growing up and there was just alcohol then,” Scott said.

Scott said she feels like the fentanyl crisis is a worse problem and called it “evil.”

“Don’t know how to reach them, how do we reach our people?" Scott said. "To bring them back?”

But don’t underestimate the people of the sea, the Lummi. For millennia, they’ve shown their strength and resilience, and this time is no different.

“It’s going to take a lot of work and it's going to take the community to do it, but we can do it,” Morris said.