TULALIP, Wash. — Advocates say many Native American women – in an effort to combat the plague of missing people in their communities – often put together a safety system to protect themselves: it’s called “the plan.”

Native American women in Washington state are four times more likely to go missing, compared to white women, according to the Seattle Indian Health Board (SIHB). Research from the SIHB reveals the city of Seattle and Washington rank among the highest in the nation for missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG).

In Abigail Echo-Hawk’s home, everyone in the family knows about “the plan.”

“These kids, along with my own, they know that if their aunties or if their mom ever went missing that we would never have left them on purpose,” said Echo-Hawk, the executive vice president of the Seattle Indian Health Board.

It’s a plan, Echo-Hawk said, every Native woman she knows has had to make – what her family should do if she were to disappear.

“They would need to make sure someone came and looked for us,” Echo-Hawk said. “In my office, right now, there is a dress. I'm an artist. And on that dress are my handprints and red ink. And in my handprints, you can see I very purposefully ensured that my fingerprints were there. And I did that with my sons. And I told them, ‘If I ever go missing, here's where you can find my fingerprints if you need to identify my body.’”

RELATED: Washington state has the 2nd most missing Indigenous people in the U.S. Here's who is still missing

Highest rates of MMIWG in the country

In Washington, Indigenous people are going missing or being murdered at the second-highest rate in the country, according to the Urban Indian Health Institute. The latest data from 2018 shows 71 MMIWG cases in Washington. Seattle itself ranks as the city with the highest number of cases nationwide with 45.

The latest figures from Washington State Patrol records show 126 Indigenous people in the state who aren’t accounted for.

“Research has shown us that the primary perpetrator of the acts of violence against Indigenous women and girls are white men and predominantly white men who come onto reservations or target Indigenous women within urban settings,” said Echo-Hawk.

With fewer resources, Native American families are forced to take matters into their own hands and form plans for their loved ones.

‘We don’t want her flame to go out’

“I've actually posted something on Facebook – if I ever go missing, know that I didn't do it on purpose. Come look for me. I wouldn’t just disappear,” said Nona Blouin, who has spent the past two years looking for her own missing sister.

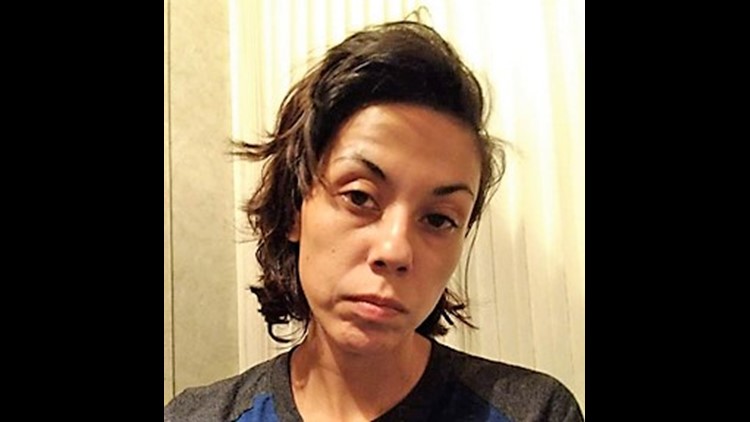

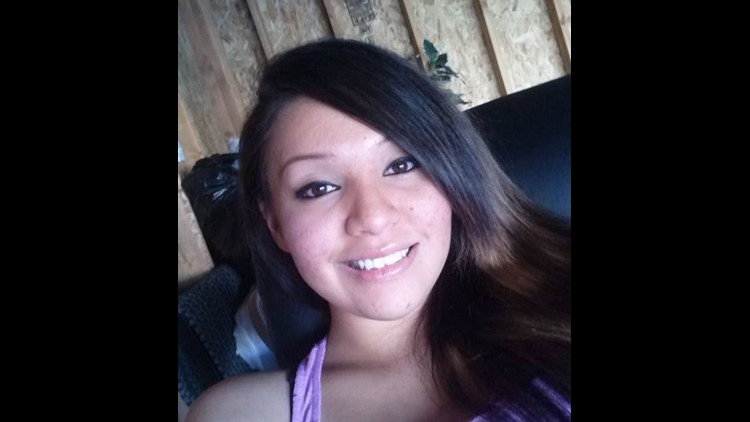

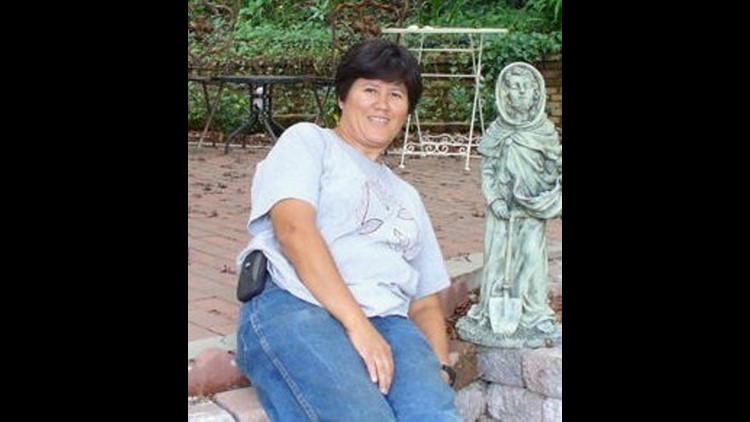

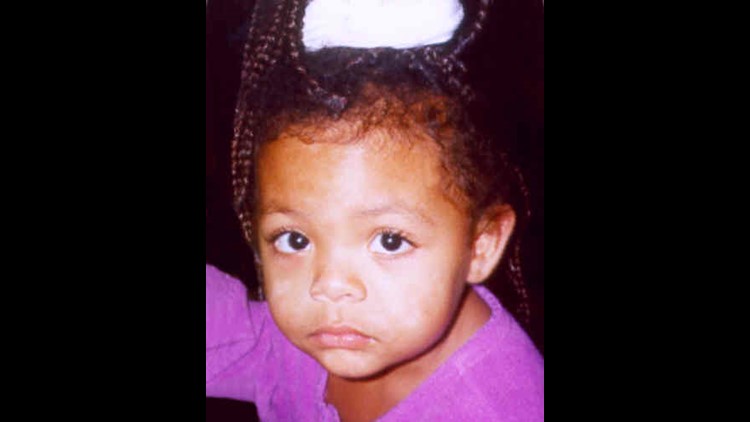

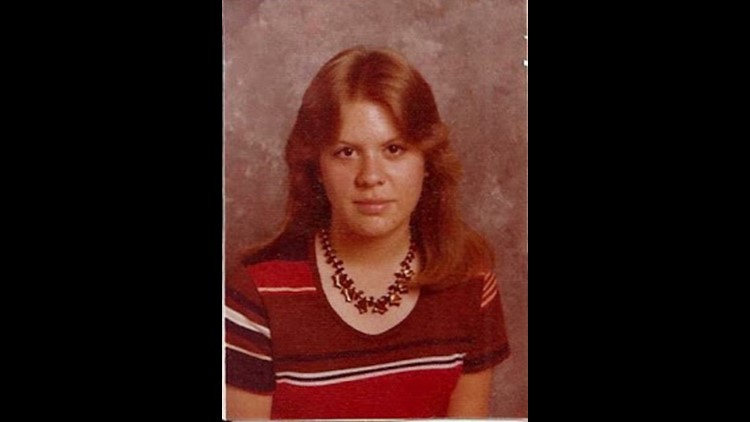

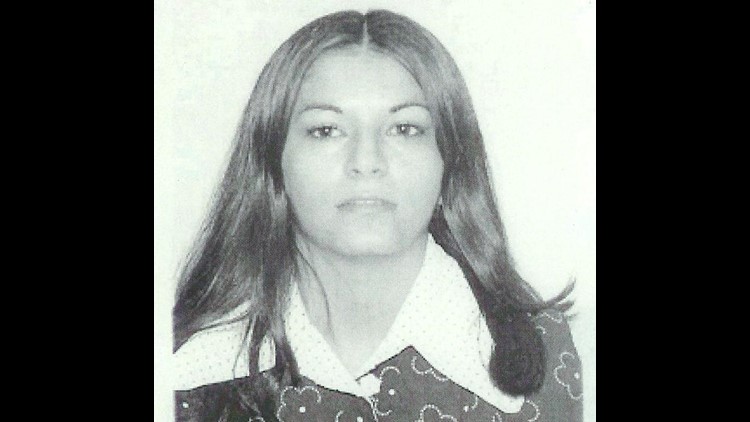

Mary Johnson, 40, was last seen Nov. 25, 2020, walking east on Firetrail Road on the Tulalip Reservation.

“We don't want her flame to go out,” said Blouin. “So, we're trying everything we can to keep her name and face up there.”

Johnson’s sisters, Nona and Gerri, believe she may have been a victim of human trafficking.

“My little or eldest daughter, she's like, ‘Mom, can we email the chief and ask where she is? Mom, why aren't they looking for her? How come she's not home yet? She can't be that lost.’ I didn't want to tell her that she was missing. So that's what I told her,” said Blouin.

Tulalip Police Chief Chris Sutter said police believe Johnson trusted someone and got into a vehicle that hasn’t been seen since.

Sutter sees Johnson’s case as a continuation of what’s been happening to Indigenous people in America for centuries.

“Historically, you know that the wrongs that have been committed, including abductions and murders and rapes and all forms of sexual assaults and other types of abuses, have gone unpunished and unprosecuted, and so this has been perpetuated for centuries,” said Sutter.

And it’s because of that history Sutter has talked to his own children about “the plan.”

“My children have all heard dad preach to them about (how) to be aware of their surroundings and their situation and don't trust people,” said Sutter.

Art meets activism

Back in Seattle, Echo-Hawk hopes future generations won’t need to prepare for their own abduction or murder by having a plan.

“Having a plan is part of the hopelessness that's experienced by our communities,” Echo-Hawk said. “It's not something anyone should have to do.”

Until then, Echo-Hawk creates hope from unlikely sources.

When the Seattle Indian Health Board asked for personal protective equipment during the pandemic, the federal government sent them body bags instead. However, Echo-Hawk is using the body bags to create art as a way to highlight the issue of missing and murdered Ingenious women.

“I’m really thinking about every single person as a blossom, as beloved life,” said Echo-Hawk as she sewed pieces of those body bags into flowers.

The blossoms will adorn a skirt patterned with red, yellow and black handprints.

One of her works, which was also made from body bags, was featured in Vogue Magazine last year.

“There is hope on healing the past so that we have full healing for our community,” Echo-Hawk said. “I refuse to let the hopelessness be all the conversation.”

How to help

If you have any information on Mary Johnson’s disappearance or any other missing Indigenous person, contact the Seattle FBI office at (206) 622-0460. To submit a tip regarding a missing person case to the FBI, fill out the form here. You can remain anonymous.

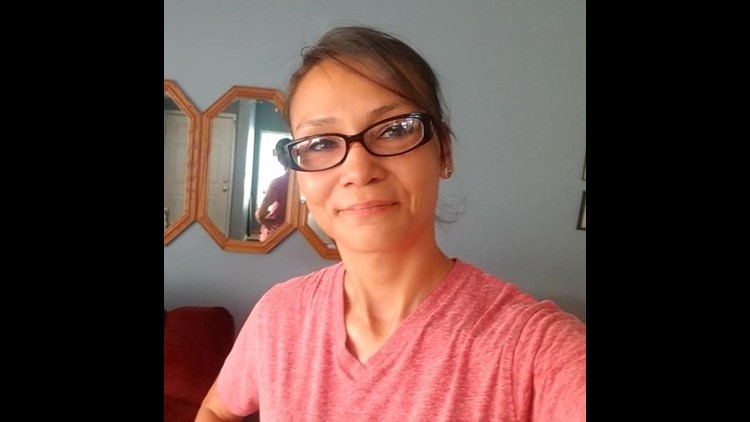

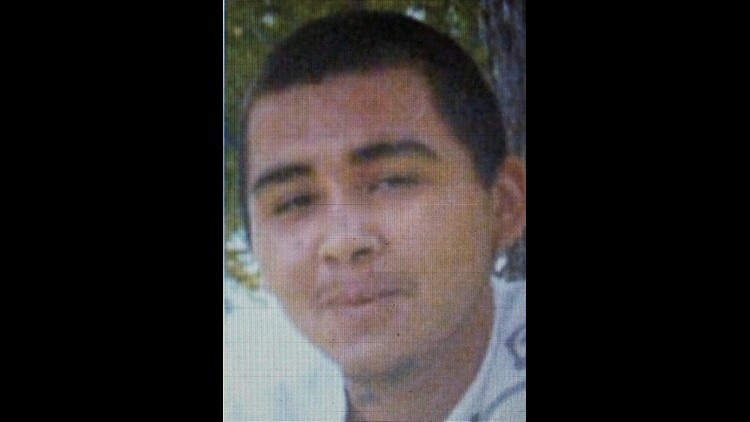

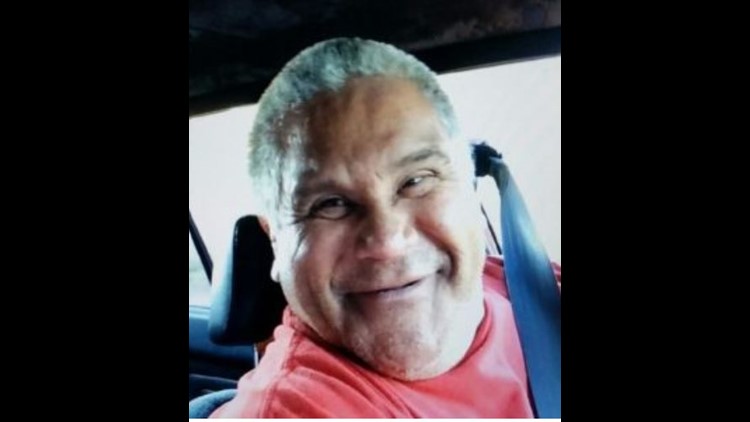

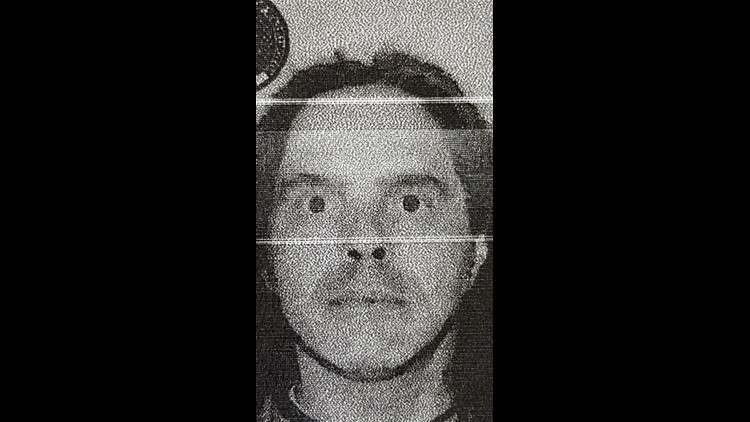

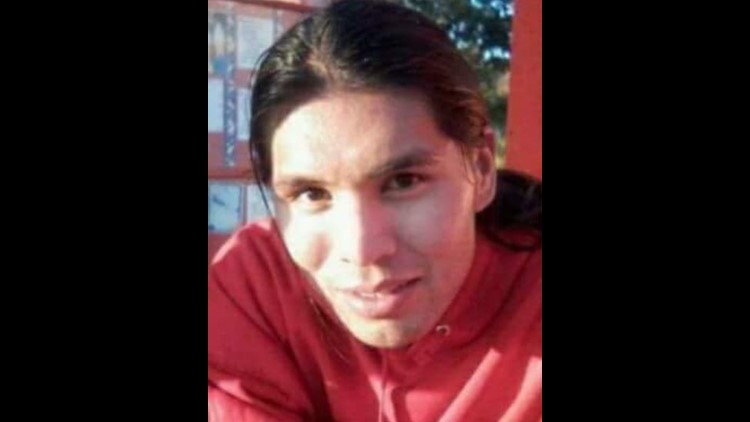

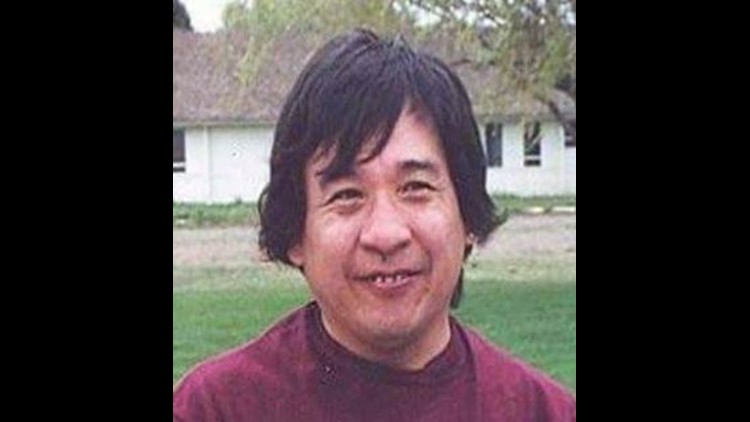

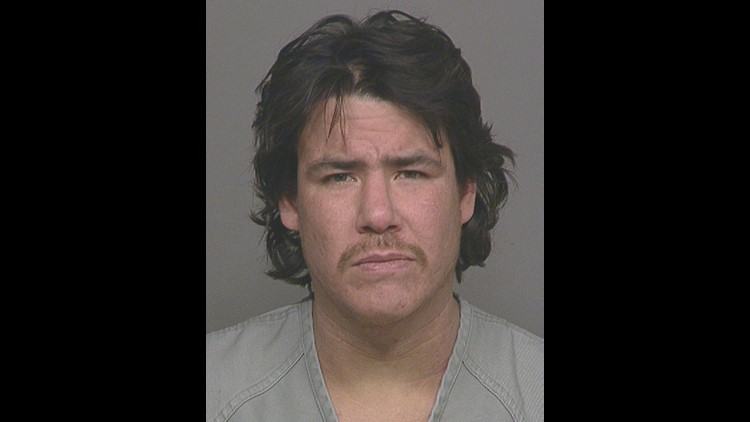

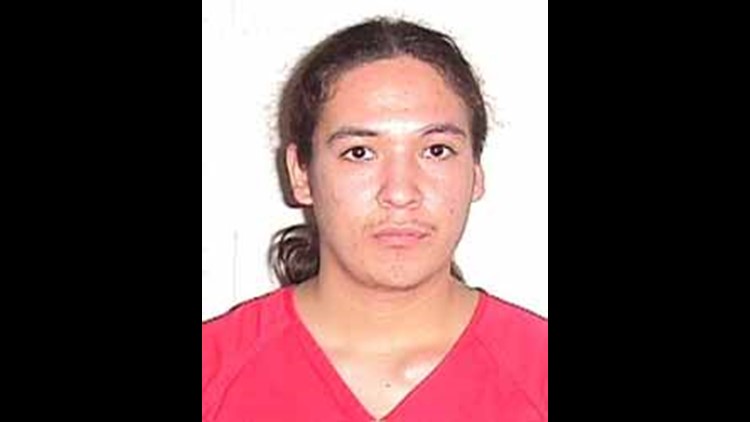

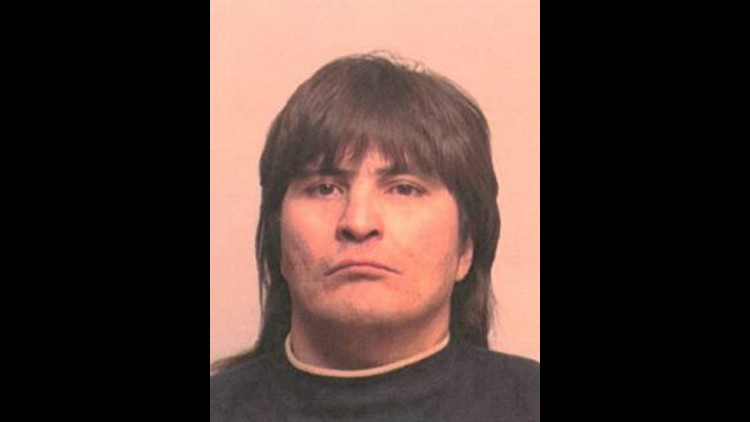

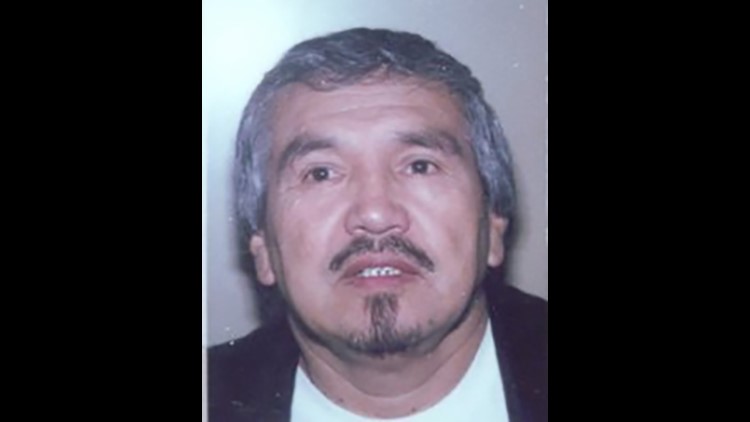

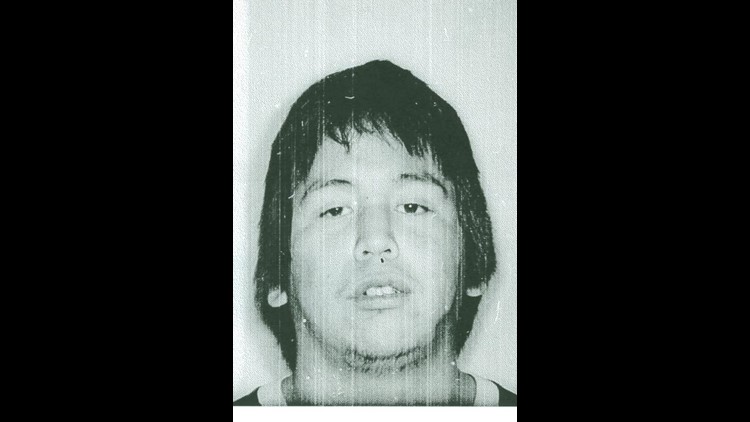

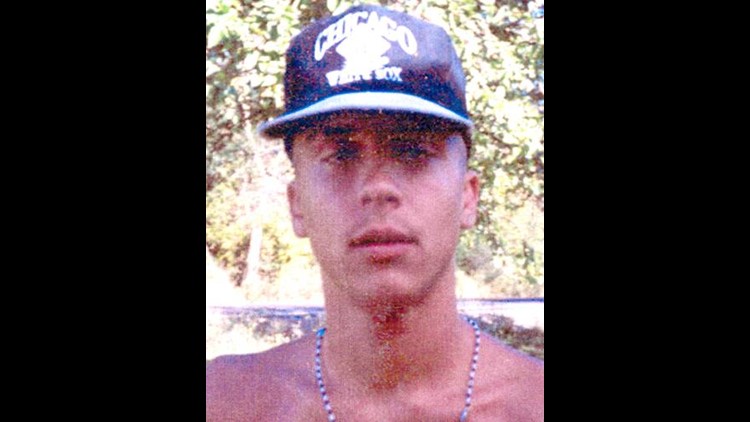

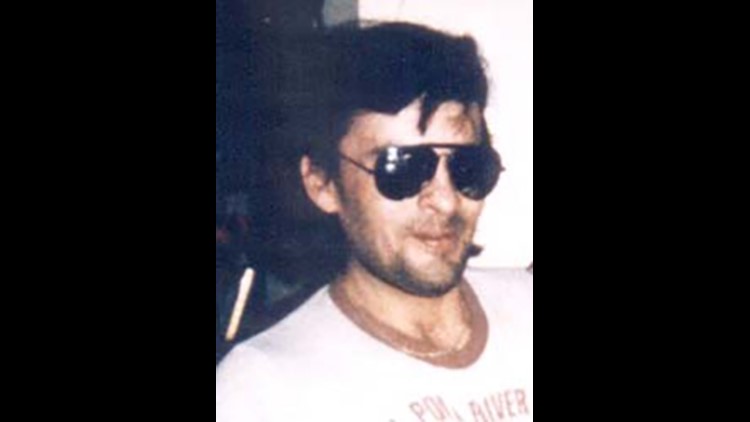

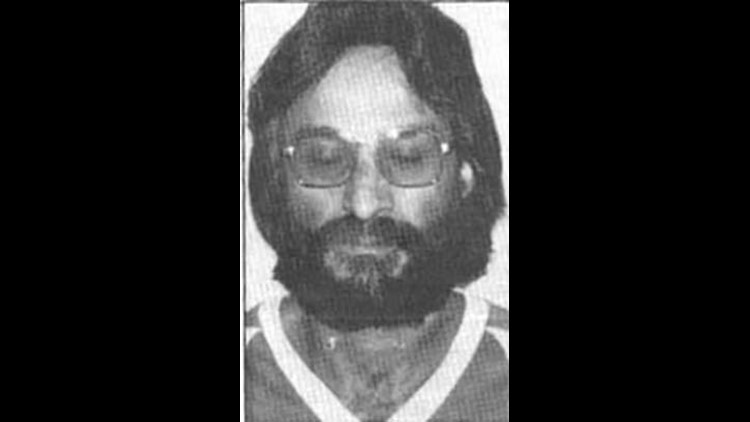

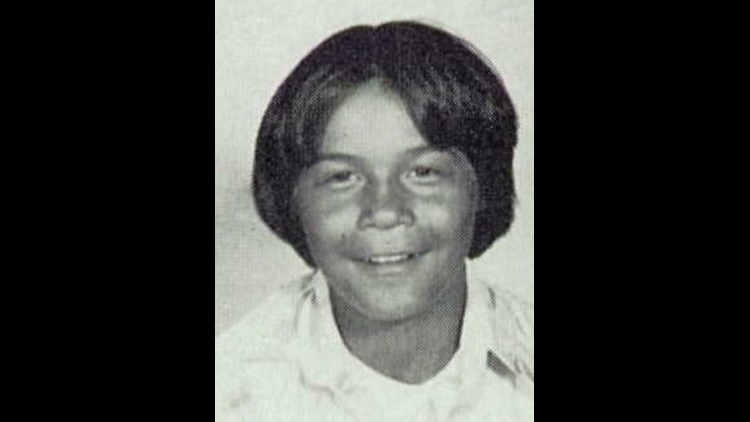

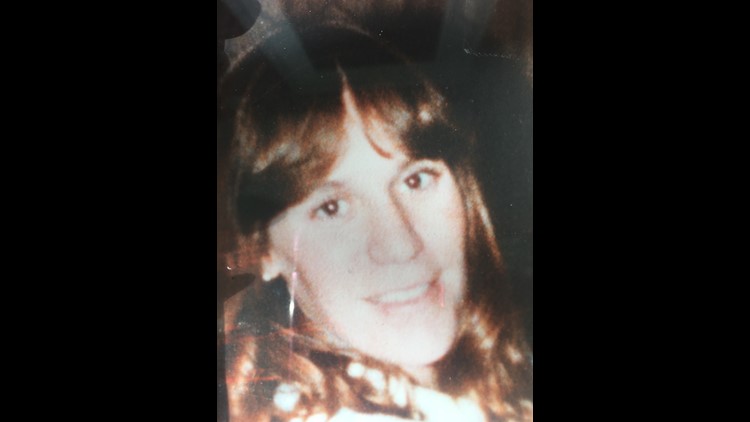

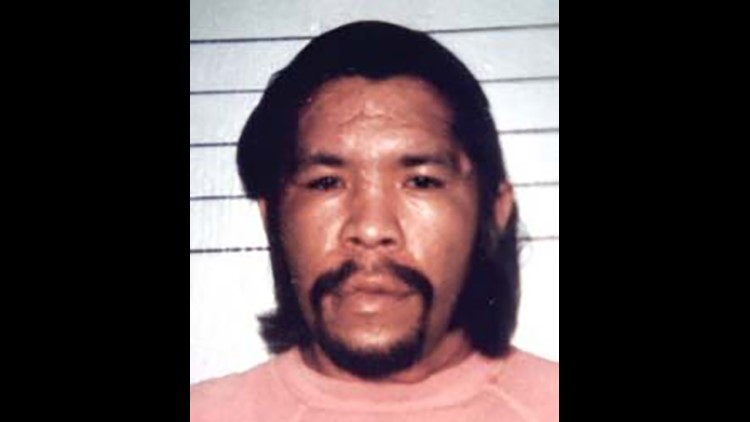

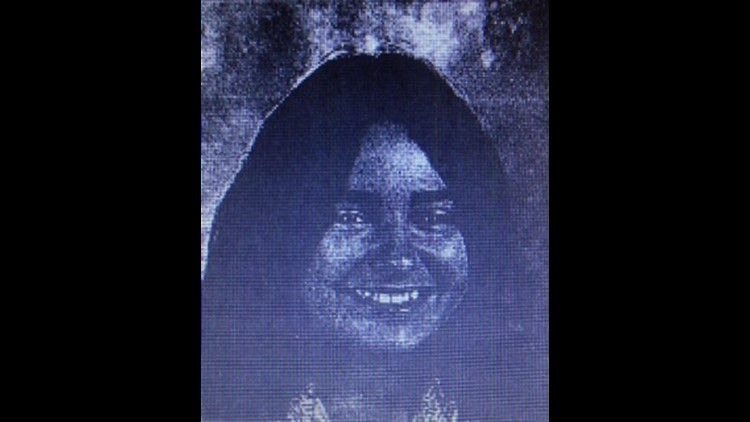

The Washington State Patrol lists all missing Indigenous people in the state on its website. In the gallery below, see the 54 Indigenous people who are missing as of May 2, 2022.