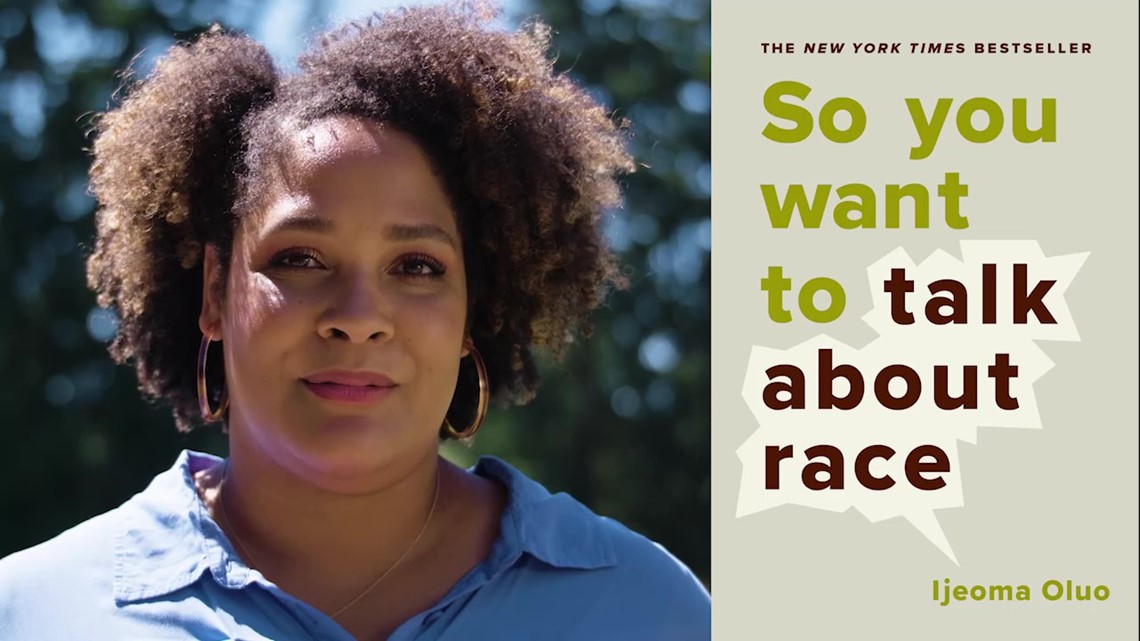

Ijeoma Oluo, a Seattle-based author and activist, has spent years teaching people how to have frank and fearless conversations about race.

But she said she’s seen “an unprecedented level of interest” in her work since a Minneapolis police officer killed George Floyd in May.

As protests for racial justice erupted across the country following Floyd’s death, Oluo’s 2018 book “So You Want To Talk About Race” soared to the top of The New York Times Best Sellers list. In her book, Oluo, who is biracial, explores the uncomfortable talks she’s had with her own family members. She also answers race-related questions for people who have no idea where to start, like, “What if I talk about race wrong?”

“This is absolutely a once-in-a-lifetime moment so far,” Oluo said. “I hope it’s certainly not the last time we show this sort of interest.”

WATCH: Meet Ijeoma Oluo

Oluo sat down with KING 5’s Christin Ayers in August to talk about why she believes this moment is unlike any other in history, and what she hopes will happen next.

The following is a partial transcript of their conversation. Some of the questions and answers below have been lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

Ayers: “What has changed for you since the killing of George Floyd?”

Oluo: “Right now there’s an unprecedented level of interest in my work and the work of many other people who are writing on issues of race and racism in America and also nothing’s changed at the same time. There’s a lot of interest, but I’m still a Black woman trying to do this work. A lot of the conversations we’re having are the same. I’m still trying to navigate myself as a Black woman traumatized by what’s been happening, trying to protect my family, trying to explain to my children. That’s all stayed the same. It’s just the conversation is a lot bigger. But I also feel like right now we kind of have a unique opportunity to advance the conversation in ways that might have been hard before.”

Ayers: "How have those conversations about your work changed? Has there been a shift in the kinds of questions you get because of the events of the summer?"

Oluo: "It used to be that I would be invited to speak and the questions would be, ‘So is racism bad? Is it really as bad? It’s better than it used to be right?’ But I think what we saw (after) the horrific murder of George Floyd, we saw that many corporations and entities were compelled to make statements about Black lives. And then when they made their statements, people within those spaces said, ‘Since when? Since when did Black lives matter? Have you met me? Do you know how I’m being treated in this space?’ And suddenly people really had to put up. They had to really put their money where their mouth is and really show change. So what I’m hearing from a lot of people is, ‘Oh, I really have to do some work. Can you help me figure out how the work is done?’ Instead of, ‘Can you help me feel like there’s not a problem?’ Or maybe, ‘Can you give me two hours to feel bad about a problem so I feel like I did something?’ Instead, a lot of what I’m hearing is, ‘People are expecting me to do something that really makes a difference. How do I get started?’ And that is progress.”

Ayers: “It seems like there is just this thirst for information on this subject right now that we may never have seen before. Is that accurate?”

Oluo: “Yeah, I can easily say absolutely not in my lifetime have I seen this intense of a focus from primarily white people—especially on what is happening in this moment and what has been done. This is absolutely a once-in-a-lifetime moment so far. I hope it’s certainly not the last time we show this sort of interest. But yes, it really is unprecedented.”

Ayers: “A lot of people have been calling it a national reckoning on race. Is it that?”

Oluo: “I don’t know if it is yet. The reckoning depends on what we do with this moment. I think that right now we have an opportunity. Whether we’ll be able to call this a true reckoning depends on how we’re willing to look at it and whether or not we’re willing to face the reality of the situation when it comes to race and ethnicity in this country and what we’re willing to do about it. It will only be a reckoning if we decide to make it so — if we decide to make real change.

I think a lot of times when we focus on interpersonal racism, what we want is a different system that produces the results that make interpersonal racism unacceptable. So it’s not necessarily that we want to make sure that every time it goes viral that a white person did something racist against a person of color, that they lose their job. What we want is that any employer would make it clear that racism is unacceptable, and if you’re a racist, that you cannot work there so these things don’t happen.

Maybe if you knew you’d get fired you’d stop doing it. That’s when we get to real progress — when it’s not just we wait until the blatantly racist thing happens and respond, but instead, we proactively create a culture that is actively anti-racist. That’s when we get to the real results that are long-lasting.”

Ayers: “What really does need to happen for this to become a true turning point?”

Oluo: “First, we really need to look at how Black, Indigenous and other people of color are impacted by racism in day-to-day life. It is not just, ‘Someone said something mean to me. Someone said the n-word.’ It’s not even just, ‘Someone said they’re not going to hire me because of my race.’ It is, ‘How are our children being treated in schools? What sort of expectations can we have for safety in our neighborhoods?’ It is, ‘How are we represented in our government?’ And we need to look at that and say, ‘How do we interact with these systems and what change can we make?’ Looking at schools and saying, “OK, well if our children are being targeted by school resource officers, let’s get them out of our schools.’ That’s a systemic change, instead of saying, ‘We’re gonna wait until one officer does something.’ (Instead) say, ‘The data’s here. We know what’s happening. We know how we’re being impacted. We’re going to change the system.’ We need to be doing this in our city councils, in our workplaces, in our towns, our communities, our schools. What are we prioritizing? What can we actually do to remove the barriers to wealth, health and safety for people of color in this country?"

Ayers: "What do you say to some of the critics who say that if white people are not actively fighting racism, that they are participating in racism? There are those who say that’s too extreme an argument. What are your thoughts?"

Oluo: “I think it’s important to realize that these systems are designed to work without our intent — that these systems don’t care about our intent. They may exploit ill intent for its benefit, but they’re supposed to just kind of run on autopilot and yes, we do participate in them and it’s important to know that, because the truth is whether you think it’s extreme or pessimistic, it will keep happening whether you believe in it or not, and you will keep contributing to it whether you believe in it or not. I instead want people to understand that if you are to invest in anti-racism, that this is actually a really empowering concept to understand. Because instead of it being, ‘I have to go find the people who hate people of color and spend all of my time convincing them that people of color are human beings, and then I will have made progress,’ you can say, ‘Wait a minute. How am I participating in systems of racism? What can I do differently in my work life, my spending life, my voting life, my social life to make a real difference?’ That’s empowering. But you have to kind of sit with those hard truths, and if you are willing to do that, you can make real change. But if you’re not, the reality of how you interact with these systems doesn’t go away. You’re just trying to ignore it.

We have to step away from the idea that racism is built off of the hearts and minds of racist individuals. It is a system that was put in place a long time ago to kind of exploit our day-to-day lives, to exploit our ability to ignore the way systems work. And part of the ways in which these systems protect themselves is by sharing this narrative that racism is just hatred, that racism only exists because a certain few white people hate people of color instead of, ‘We are all participating in a system that is meant to exploit some people for the advantage of others.’

When I ask people, ‘When I say someone is racist, what do you think?’ so many times people will say Klan members, and (Klan members are the) very extreme minority. The Klan is not powerful enough to explain why the average Black household in the United States has one-thirteenth the net financial worth of the average white household in this country. What we have are systems and we all participate in them.

I want people to shift from thinking (racism) means that you are racist all of the time to thinking, ‘You have a responsibility and an opportunity all of the time, and if you really believe that racism is an evil — that must be eradicated — then you will engage with your privilege and take the opportunity to do more. But now that I’ve told you, you can’t act like you don’t know….Once you become aware — no matter how much you complain about it — you can’t say you’re ignorant. And I think oftentimes, that’s when people get upset because they didn’t want to know. They wanted to continue going about their life and think, ‘If I never said the n-word in my life, I wasn’t racist, and I didn't hurt anybody.’ But you’re participating in systems that hurt people, and these systems are relying on your ignorance. When the tools are made available for you to do better and you find out about that, you have no excuse not to.”

Ayers: "In the simplest way possible, how can you explain systemic racism to someone who just doesn't get it?"

Oluo: “The truth is, people in power needed cheap labor. They needed land and cheap labor. They stole land through the genocide of one group of color and got cheap labor through the forced enslavement of another group of color. These are abhorrent acts, no matter what your race or ethnicity. And in order to justify that — in order to get people to participate — you have to come up with a story that makes it OK. And the story that’s been told in this country is one of racism. It’s the story that these people were meant for this work, that these people are brutes who, if not controlled, would be violent, untamed. ‘These people are built for hard labor.’ This story is what makes the majority OK with this treatment. It’s also a story that locks other people into their roles. So it’s a story that also tells poor whites, ‘Hey, you’re not as poor as you think you are because you have power over these people. You’re doing better than this group of color. If you play along in the system, you will benefit,’ — even if they may never benefit. That is the story of racism, and in that, all of our systems were built. It’s important to recognize that that initial creation was fictive. It was not based in true animus. It was not as if rich, white colonizers came here and said, ‘Oh, I can finally get revenge against Native people and Black people.’ it was, ‘I need cheap labor. I need land. What lie can I make up to justify this?’ And the system has never required that you hate people. It’s never required that you go out and try to steal from people. It has only required that you buy into the story and play your part. So our school systems were built around this. Our economic systems were built around this. Our government systems were built around this….

What is really endangering the lives of BIPOC people (is) not, ‘I’m walking down the street and someone shouts a slur at me.’ (It’s) if I go to a doctor, I’m less likely to be listened to or believed when I’m exhibiting dangerous symptoms, that when I go for a job interview, if my name sounds Black, I’m less likely to be called in. If my children are roughhousing in school, they’re more likely to be seen as violent rather than as children at play. These things impact my life, my safety, my ability to have a secure family, and they are systems.

What we need to do if we actually want to make an impact to undo and prevent the harm that systemic racism does, we have to work within the systems instead of this whole, ‘Let’s all learn to be best friends and love each other.’ You can love someone of a different ethnicity and still actively participate in their oppression based on how you vote, based on what you bring up in your office meetings, based on where you spend your money.”

RELATED: What is systemic racism in America?

Ayers: “What is the term ‘white privilege’ and why is it so triggering for a lot of white people?”

Oluo: “I think of privilege as a set of barriers that you didn’t have. So it’s not like someone said, ‘Here’s your wealth because you’re white. Here’s your status because you’re white.’ It simply means that the barriers that we’ve placed in front of people of color were not placed in front of you. You may have a whole other set of barriers. You may have barriers of disability, barriers of class, barriers of immigration status, so many other barriers that were placed in front of you. But acknowledging privilege is simply acknowledging if we also took that other set of barriers that we place in front of people of color, you would stumble even further.

It’s really not about saying ‘You’ve never suffered’ or saying, ‘You don’t deserve anything you have.’ It’s saying, ‘Whatever you have overcome in your life, whatever you have accomplished would have been more difficult if we had set this set of barriers in front of you.’ It’s important to recognize that — not because you need to walk around feeling bad all the time or feeling like you didn’t earn what you have, but because you need to recognize where you are participating in systems that normalize your experience and ignore those barriers.

So where I, as an able-bodied person, can freely walk into a restaurant regardless of ramps, I need to recognize that I have been programmed to not even look for a ramp or ask a question. And I am the person in the building. I am the person most poised to ask and say, ‘Where’s the ramp?’ But because I don’t see it or recognize that set of barriers, I am neglecting my duty. I am failing my peers who are disabled.

It is very similar for race. When you don’t recognize these barriers that are placed in front of BIPOC people, and you just benefit from it and think that’s the way it’s always been, you will end up participating in it. You may end up hiring someone with the same expectations that were put in front of you — not realizing that those rules are different for BIPOC people or maybe the access is different from BIPOC people. You may vote for representatives thinking they represent you because they’ve always represented you, and (you may) not recognize that there may be a different set of needs for BIPOC people because of the situations they have been placed in. (You may) think you are voting for equality when really you are just voting for whiteness.

These are all opportunities to actually just divorce ourselves from systems of oppression and make real change. But that means we have to kind of be willing to face it and recognize that we all have privilege, and it’s OK to acknowledge our privilege. We have to acknowledge our privilege because it’s really the only way we can undo the ways in which we participate in harm."

Ayers: "Does it seem, from your vantage point, that we are actually on the verge of making progress on some of these things and dismantling certain systems? Are we on the right track?"

Oluo: Yes, I think we are in certain places. I think what we have right now is a collection of opportunities across the country that we need to take advantage of and push forward. But yes, I think that I and many other people doing this work did not think that we would be talking about defunding the police because last year, the year before, the year before. We were trying to talk about fundamental change and instead spent most of our time trying to convince people that racism existed at all or that police brutality was even really a problem. That we’ve been able to push past that is progress. It’s shameful progress 400 years into this system, but it’s also progress I wasn’t expecting this year, right? I don’t think we’re going to wake up next year and see an entire country changed. But I do think we have the opportunity to see real, fundamental systemic change in pockets all over this country, including here in Seattle, that we can build upon, that we can look at and say, ‘Hey, we did this with our police system here, and it worked. We did this with our school system, and it worked. We did this and it didn’t work. And now let’s move on. What happens next? What happens in these other cities and towns?’ That’s really how change happens. We latch on to it where we can. We make fundamental change. We build upon it. We spread that change and we encourage other cities and towns to do the same. And I do think that we have an unprecedented opportunity for that work all over the country."

Ayers: "Is it natural that we see a falloff here or are you optimistic that there can be lasting change?"

Oluo: "I think it’s a bit of both. I think of course we are going to see some fall-off, and I think part of that is because we haven’t figured out in this current generation how to sustain long-term resistance, and we need to.

What we can do to support that — to keep that movement going — to continuously keep the conversation going in ways that don’t just look like massive protest, is what really matters. What we do to hold our leaders accountable to the promises they’ve made these last few months really matters.

Pay attention to the promises that have been made by local government, by police forces, by schools and by your employers and hold them to it. Don’t let it just be a sound bite. Make it something that people have to work on and continuously communicate what is and is not being done so that we know when we do need to get right back into the streets and when we really do need to raise the volume on what we’re saying to make sure the fundamental change really happens.

I absolutely see hope, especially when I look at younger generations. The conversations that people my age and older are having, my children aren’t having nearly as much. Like, they get it and they’re just pushing forward for change. When I see young Black people and other people of color knowing that they have absolutely the right to fully participate in our systems, to really have full, vibrant futures and they’re fighting for it, even knowing our histories and knowing that the odds are stacked against them, that they’re still out there, I’m so hopeful. They are investing in us just like we need to invest in them."

This story was produced as part of “Facing Race,” a KING 5 series that examines racism, social justice and racial inequality in the Pacific Northwest. Tune in to KING 5 on Sundays at 9:30 p.m. to watch live and catch up on our coverage here.