SEATTLE — Systemic racism created barriers for Black and BIPOC families to become homeowners. Nearly a century later, several challenges remain.

In King County alone - Black homeownership has been on a noticeable decline. Fifty percent of Black residents owned a home in 1970 - but in 2022, that number now stands at 28%. In the most recent census reports, 62% of White families are homeowners, according to the University of Washington's Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium.

In the 1930s - the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) insured private loans that were awarded to millions of White families.

According to Habitat for Humanity, that "hand up" helped build a foundation for white American families. However, BIPOC families, particularly Black families, were prevented from receiving the same benefits and subsidies through the practice of redlining.

The federal government's Home Owners' Loan Corporation created color-coded maps that identified households where people of color lived and deemed those "redlined" areas as unsafe for lending.

Dana Frank, the current owner and operator of Frank Family Properties in Seattle, said redlining occurred in the Central District - a then predominantly Black neighborhood.

Her family experienced the racist housing practice firsthand in the '50s and '60s.

"We grew up putting pickets on banks, you know literally banks and bankers' homes to amplify the injustice of redlining and just to expose it," Dana said. "We were refused."

The FHA refused to insure loans in redlined communities which prompted nationwide private lenders to follow suit.

Despite not getting a home loan, Dana's father, Gerald Frank, bought his first home in 1950 near the University of Washington campus through a private contract with the property owner.

"This was long before Airbnb," Dana said, "In order to make the $48 monthly note, he rented out rooms to his fellow students at the university."

Coming to Seattle

"When he came from Detroit he was changing the narrative," Dana said. "His options were to go work for that either Chrysler or Ford, put in a long shift on an assembly line and come home at the end of two weeks with barely enough of a paycheck to put a decent meal on the table."

During the practice of Jim Crow laws, Gerald, who passed away in 1996, left Detroit and drove as far as he could.

"He got to Seattle and when he saw Mount Rainier and the Olympics and Lake Washington, he just thought he was in God's country," Dana said.

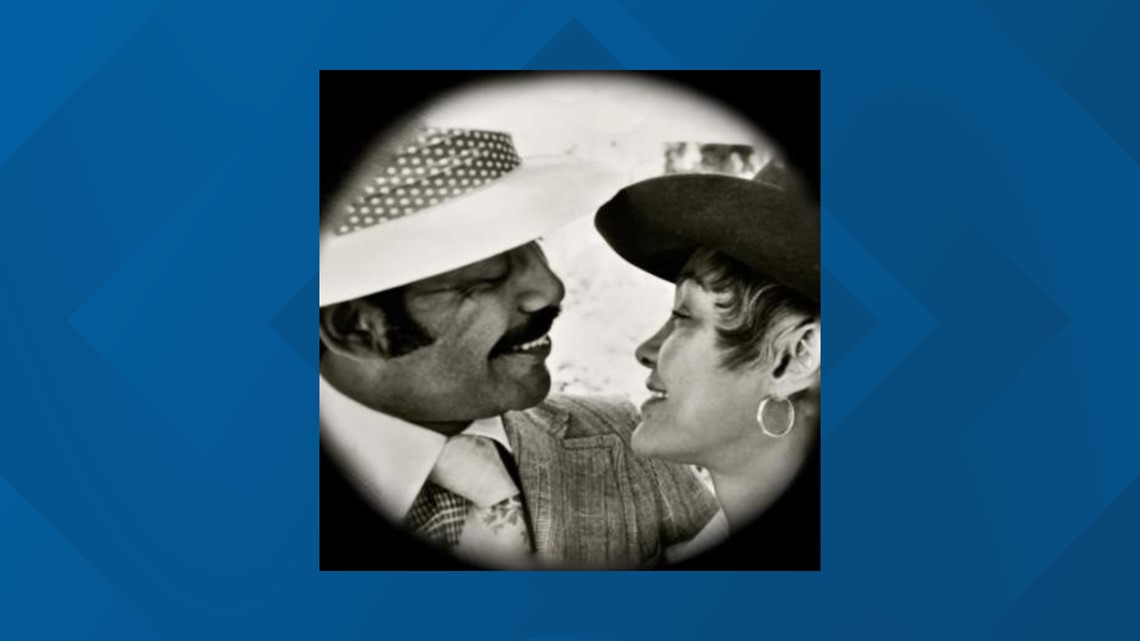

In 1954 - Gerald met his future wife, Theresa.

"I call these individuals, fire starters," Dana said.

Creating generational wealth

For 15 years, Dana said her parents purchased at least one piece of property every year.

They used creative funding and worked with partners until they could buy them out to own properties outright until 1969 when Black-owned Liberty Bank gave them their first loan, according to Dana.

The Franks wanted to create generational wealth for their family's future through property ownership.

As of this year the business owns and operates a few hundred units across the Central District and Columbia City neighborhoods.

"We were raised with cash erodes, equity grows," Dana said.

Real estate would be the ticket to growing equity for decades to come. The Franks viewed this as an investment in property, but also an investment into the community by providing rental housing.

"Starting from zero, just working our way up," Theresa said. "To build this and to pass it on to the children is just amazing."

At 91 years old, Theresa often reflects on the many stages the family business has gone through.

Her grandson, Brett Frank-Looney, said he is honored to be working with his grandmother and mother.

"I wouldn't be sitting here without their knowledge and their hard work," Brett said. "The impact that my grandparents started so long ago."

Dana's daughter, Taryn, is finishing college. She is also getting her real estate license. Soon, she will join the family business.

The hard work and perseverance of each generation have proven to be a source of success.

However, the family's success in property ownership is rare compared to other Black and BIPOC families in King County.

Continued homeownership disparities

"There's a lot of discrimination in the housing market," said Kyle Crowder, the department chair of UW's Sociology Department.

Crowder said the deep-rooted racist housing policies from the 1930s are still holding back Black families today.

Four main components contribute to King County's Black homeownership drop-off, according to Crowder: declining affordability, household income disparity, lack of intergenerational wealth and limited access to credit.

"Black folks are also much more likely to be denied a mortgage than our white folks, who have the same level of income in the same kind of financial characteristics," Crowder said. "Blatantly kind of racist ideas are built into the algorithms that are used to decide who gets a mortgage and who doesn't and who gets a favorable market rate."

Even though redlining and gentrification are recognized as racist, Crowder said not enough is being done to stop and reverse homeownership disparities.

Several advocacy groups are working to achieve this.

Western Washington Realtist (WWR) is the local Board of the National Association of Real Estate Brokers (NAREB).

NAREB was founded in 1947 to secure the right to Equal Housing Opportunities regardless of race, creed, or color.

Nicole Bascomb is the current president of WWR.

"If it was made equitably, everyone could get to provide wealth building for a family," Bascomb said. "Nothing does that like real estate."

Bascomb said the government needs to step in and establish equity in buying homes with a multi-prong approach to address issues such as affordability and credit scoring.

Providing grants toward a home purchase versus a loan would be life-changing for Black families in Western Washington, according to Bascomb.

Several local groups are actively working to address the challenges of Black homeownership.

The Black Home Initiative includes a network of nonprofits, private companies, governments, and individuals focused on increasing Black homeownership.

Hope for future generations

"Daddy always wanted to renovate properties so Black people could live with dignity," said Dana Frank.

One of the family's proudest achievements is that so many families have chosen to live in one of their units for decades.

Some tenants have lived in a Frank Family Properties location for 40 or 50 years.

It may be surprising, but there are times when a renter's notice to move out is good news.

"My proudest moments are when we have residents that come to us after so many years, they say look, 'we put in a down payment on our home and we’re moving out in the next couple months,'" said Brett Frank. "That's what it's all about.”

The Franks said they want to see more Black BIPOC families overcome racist barriers and build their own equity and generational wealth.

In hopes of inspiring more families to set and achieve personal goals - Dana is set to release her book -Get Up and Get On It, A Black Entrepreneur's Lessons On Creating Legacy and Wealth - on June 19, 2024 - Juneteenth.

Moving on from the past

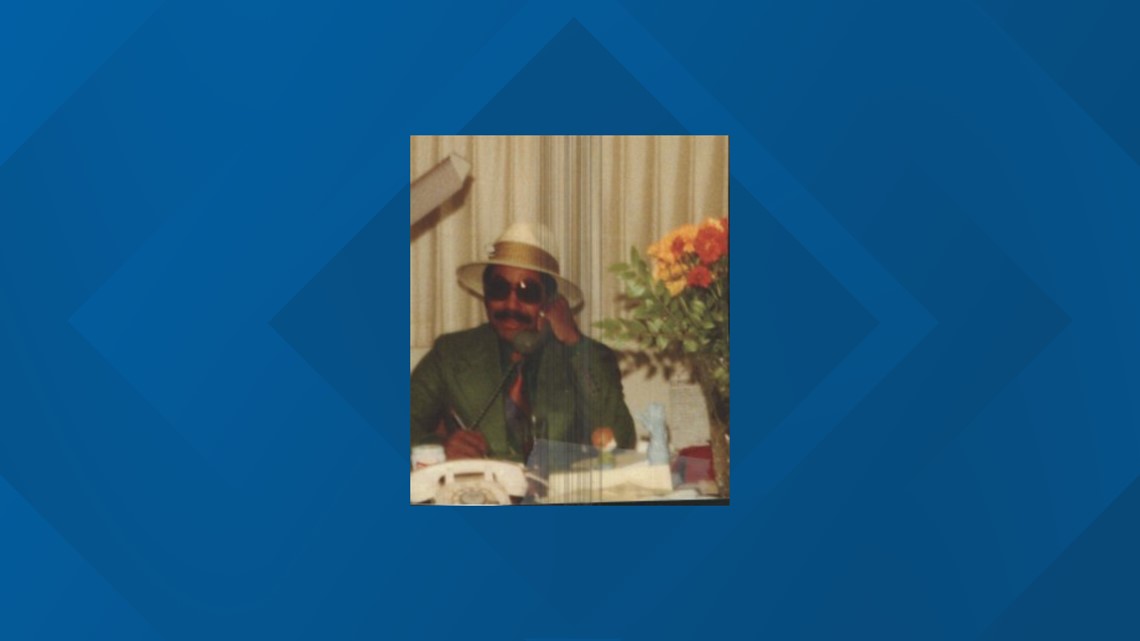

Gerald Frank, the co-founder of the family company, left a memorable imprint on the Central District. He did it, at times, colorfully and controversially. In the '50s he was a noted jazz musician. He brought topless dancing to the area and owned a prominent nightclub – the Pink Pussycat. As a landlord, he was often accused of providing sub-standard housing and evicting tenants without due process.

Dana and her children have turned the reputation around, focusing on best real estate practices and community service.

“It’s about changing the narrative,” Dana said. “Daddy was notorious in Seattle. Even though he went down that path, he realized that wasn’t the path for his family. It’s about the choices you make.”