Kim Long lives in Shoreline, but she grew up in Solon, Iowa, a town of about 1,100 people.

"I was the first person of color most people in my town had ever seen," said Long. "And I grew up on a 200-acre hog farm. Like, my culture is literally apple pie, weenie roasts and fish fries."

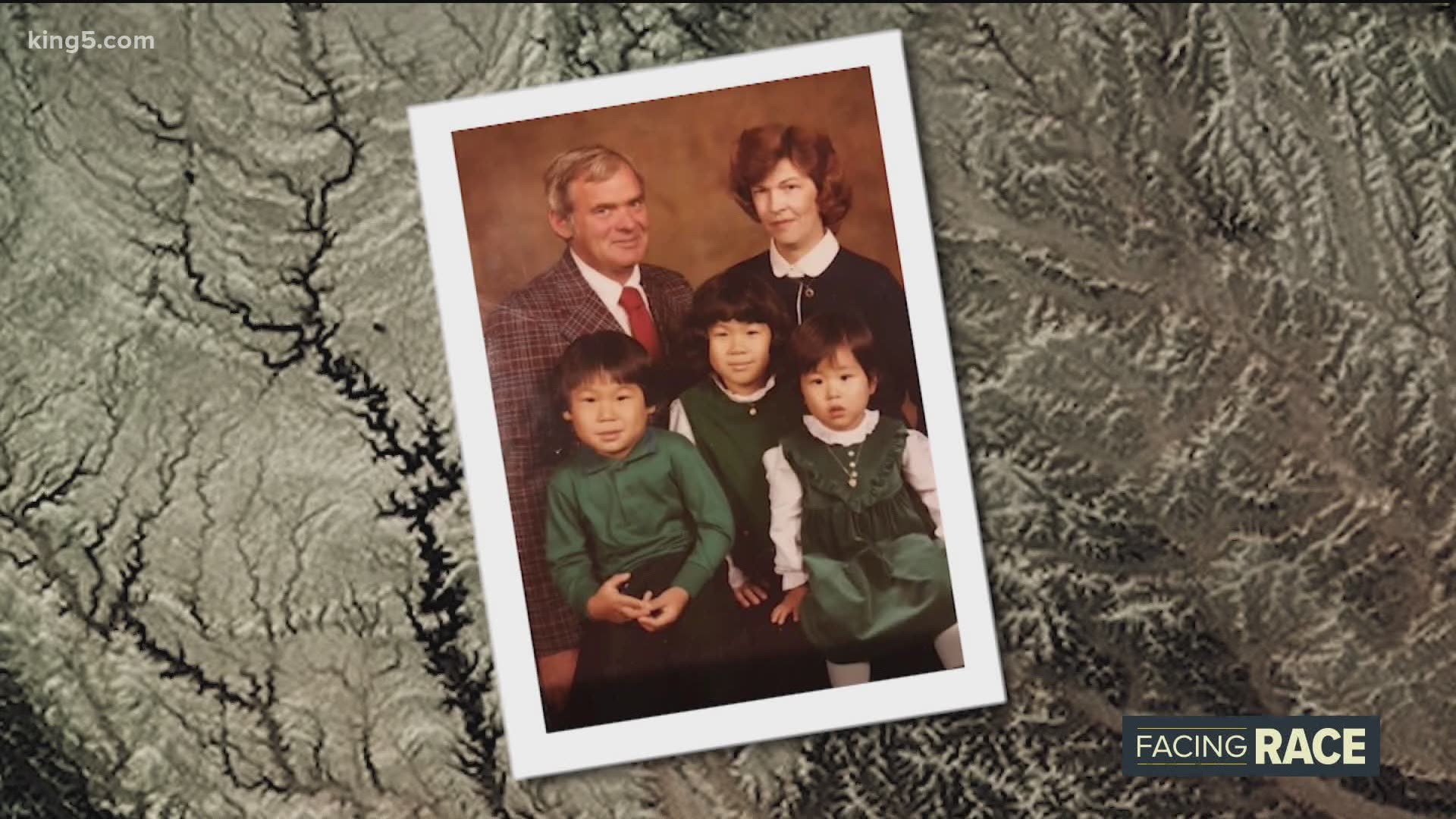

Apple pie and fish fries in Iowa are cultural points that have nothing to do with where Long was born, in Busan, South Korea. She was relinquished as a toddler with little identifying information and sent to a white family in the early 1980s. She came to the Midwest speaking the Korean language, eating staples like kimchi, a Korean staple made from fermented cabbage, and she likely slept on the floor as many children did at that time.

"I think I was like a college love child," said Long. "Then I was in foster care at the orphanage for six months, and then I came to the U.S."

Because of the Korean War, there are more Korean adoptees like Long in the U.S. than any other group – an effort started right here in the Pacific Northwest by a man named Harry Holt.

The adoption agency Holt International is still in operation today. Yet, even after five decades, adoptees like Long still face discrimination – experiences her family in Iowa didn’t share or prepare her for as she became an all-American girl.

Long says she felt out of place all the time, and it's still happening. Long just had her first baby, Juniper, and at the very first visit to the pediatrician, she was smacked in the face with a microaggression, a subtle discriminatory act. The Seattle office staff assumed her name wasn’t Kim Long, and instead, someone changed it to Kim Wong.

“Nowhere on our records was there 'Wong'," said Long. "Long is a German name."

That racist assumption is the type of encounter her family back in Iowa didn’t realize they needed to help her navigate. Back then, adoption agencies told families to raise children ignoring differences and the cultures they came from.

“We didn’t have discussions about race. We didn’t talk about it," said Long. "We didn’t say, 'Hey, were there any microaggressions that happened today?' It was a thing we never talked about. It was assimilate, assimilate, assimilate. Prepare like there is no difference.”

Experts now agree that way of thinking is outdated, and most adoption agencies do enforce traveling to foreign countries to meet their children or having sensitivity when it comes to adopting children of color domestically. However, adoptee culture is pushing for more.

"It's hard to walk around every day and have people see a Black woman, but for me to not even feel like a Black woman," said Angela Tucker on the Red Table Talk series hosted by Jada Pinkett Smith.

A white family in Bellingham adopted Tucker out of foster care, and she’s now a transracial adoption specialist who helps adoptees across the country embrace their unique stories. She is also the director of post-adoption services at Amara, a nonprofit in Seattle that serves children in foster care and the families who care for them.

"It's really dangerous for Black and brown transracial adoptees to not embrace their blackness and understand what that means in the context of today's world," said Tucker.

She's saying that if you're an adoptee who's been assimilated or ill-prepared for how the outside world may perceive you, it could even cost you your life.

Tucker mentors transracial adoptees, and she recalls helping a 13-year-old Black girl who lives in white spaces. She told Tucker that after George Floyd was killed, she went to hang out with a girlfriend who's a Black friend with Black parents and is not adopted. That friend's parents were giving their daughter "the talk," and it turned into a harsh lecture about how to react to police. When Tucker's mentee went back to her house with her white parents, she says they were hesitant to talk about Floyd or police brutality, and when they did, they talked about it apologetically, as if to say, "I'm sorry this is your reality."

Tucker says that is dangerous.

"My mentee said to me, 'I don't know if I'm prepared to be a Black woman in society as I grow up because my parents aren't telling me the same level of the truth of what I saw my Black friend and Black parents tell her,'" recalled Tucker. "I thought that was really insightful and almost unavoidable, which is why I recommend that white parents of Black kids outsource some of the parenting duties."

Tucker also admits that can also be tricky.

"It is tricky because people are like, 'Well, it's like, I'm hiring the help.' Like, go find a Black person," she said. "For some white adoptive parents, they don't have a community around them that is diverse. So, they don't have a good friend or a neighbor that they can ask to come chat with my kid about this or that. That's also problematic. If you don't have those people in your lives and you really have to look, then that also tells me that your world isn't diverse, which that is not safe for the kids."

Not only does Tucker mentor adoptees through Zoom sessions and beyond, she also launched a podcast called The Adoptee Next Door that helps shed light on topics like birth reunions and mental health. She also tackles a hot topic in today's world concerning white saviorism, the idea that white families are heroes for adopting children who are poor and often children of color.

Long says she's heard those "savior" comments her entire life.

"'Oh, well, you would have been growing up in abject poverty, and here you are. This wonderful life that I'm going to give you,'" Long gave as an example. "While completely ignoring that they are not going to experience the world the way you do."

Tucker says her focus is trying to help adoptees find who they are outside of what their parents have told them. The work being done now in the adoption community tries to honor the lives adoptees actually live, which is often floating between identities and navigating a world that doesn't always see them for who they really are.

Long says she will make sure her daughter is raised differently, and it starts with talking about race.

“I absolutely will do that with Juniper because I think not talking about it was the problem," Long said.

This story was produced as part of “Facing Race,” a KING 5 series that examines racism, social justice and racial inequality in the Pacific Northwest. Tune in to KING 5 on Sundays at 9:30 p.m. to watch live and catch up on our coverage here.