SPANAWAY, Wash. — How many Black teachers have you had?

Ask yourself or your children, and data shows, the answer is likely "one" or "none." Across the country, and especially here in Washington, there’s a critical shortage of diverse teachers.

In a Spanaway Middle School classroom, there’s something you won’t see often in the school district.

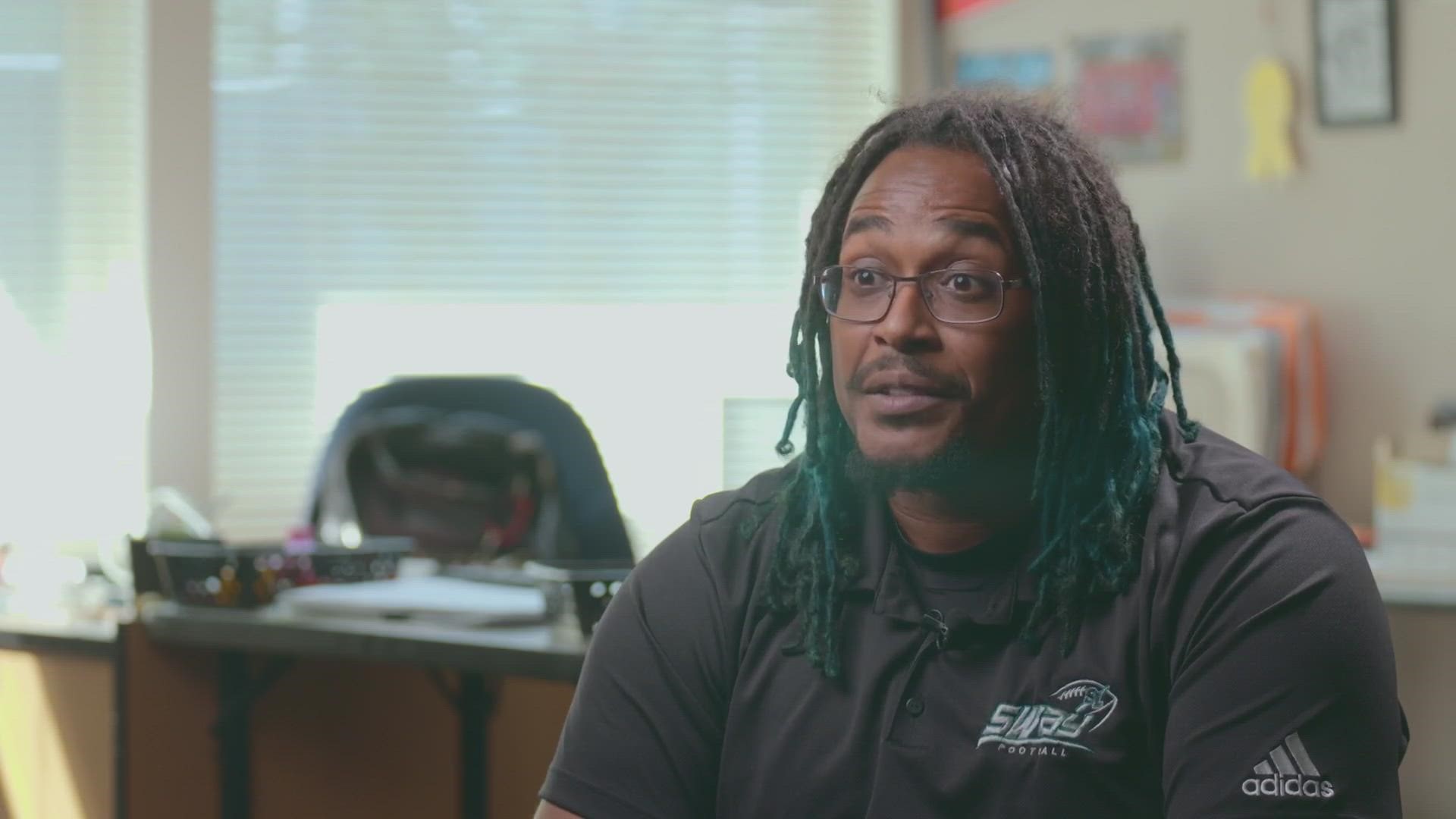

“One of my students during COVID, he goes, 'Mr. Young, I ain't trying to be racist, or rude or anything, but you're my first Black teacher ever,'" said Hakeem Young, math teacher and football coach. "And I kind of just was shocked about that. But I also thought about, I was like, 'Well, I've been in his shoes,' so it makes sense."

Young said he does not recall having any African American teachers growing up.

Ask around today and that’s still a pretty common answer.

“I've never had any Black, African male teachers in my life,” said Jericho Martin, a 13-year-old student of Young’s.

“One," a group of Mr. Young’s study hall students told KING 5. "One. Just Mr. Young."

According to the Black Teacher Collaborative, Black teachers make up just 1.3% of all educators in Washington. U.S. Department of Education data showed that’s far below the 7% national average of black teachers nationwide.

“It just shows that you know, there's not very many of us," Young said. "And then when they do run across some of us, we can make an impact."

Young said lack of representation means many kids never consider education as a career.

“I see athletes, the rappers, musicians, that's what we see a lot of growing up," Young said. "And that's where we kind of flocked to. So when they say, 'be an educator,’ it's hard to envision that sometimes."

'School to prison pipeline'

Once a parole officer working in the prison system, David Watson is now the principal of Rainier Valley Leadership Academy.

“For me, I never wanted to go into education," Watson said. "What made it my calling is you start thinking about the school-to-prison pipeline, and how you're a part of that."

Principal Watson realized early intervention was key after hearing the same regrets from countless felons.

“I've asked them some of the same questions: 'How'd you get to this point? How'd you get here?'" Watson said. "(They would say,) 'You know officer Watson, I wish someone had took me under their wing when I was in middle school, high school, I wouldn't even be here.' And that really stood out to me, because that's exactly how I was. I was one of those kids that was at risk. I was in trouble. I was on probation before I even hit the eighth grade. And I had some teachers who took me under their wing and got me on the right track."

The impact of Black teachers

Watson still remembers the impact his first Black teacher had on him in eleventh grade.

“I remember reading some books, I can't relate to anyone in these books whatsoever," Watson said. "And then the next thing you know, (my teacher) started bringing me some books, different books written by Toni Morrison, 'The Color Purple,' Alice Walker, I'm like, 'Wow, these are about people that look like me.'"

According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, Black students who have one Black teacher by third grade are 7% more likely to graduate high school and 13% more likely to enroll in college.

After having two Black teachers, the likelihood of enrolling in college for Black students increases to 32%.

Research also suggests the lived experience that comes with being a person of color also helps white students learn about bias and social justice.

“There needs to be more programs for individuals to really step into these spaces," Watson said. "Because we are missing the buck when we do not include, like so many different members of the global majority within the educational system."

Impact outside the classroom

Back at Spanaway middle school, the last school bell of the day transforms math teacher Mr. Young into Coach Young.

“He isn't afraid to be like, real," said Tucker Ralph, one of Young’s 15-year-old students. "Like, if he feels a certain way he'll tell you."

“My students get the privilege of, they see me in sixth grade, seventh grade, eighth grade," Young said. "Well, now they go to high school, they see me for a sport, so I'm still on their case about grades."

After school, you can find him handing out life lessons at the 50-yard line.

“When we around here, we don’t get nothing unless it’s earned,” Young said during football practice with his students.

Young is preparing his students to meet what challenges may come both outside and inside of the classroom.

“I understand their struggle," Young said. "When you've got people who are willing to listen to them first, before trying to tell them what they have to do. That's where the real connection comes in."