WHITE SWAN, Wash. — Fort Simcoe Historical State Park, located near White Swan, is home to one of the few remaining pre-Civil War forts, according to the state’s website.

Visitors can tour the officers' homes, and other structures, including a jail.

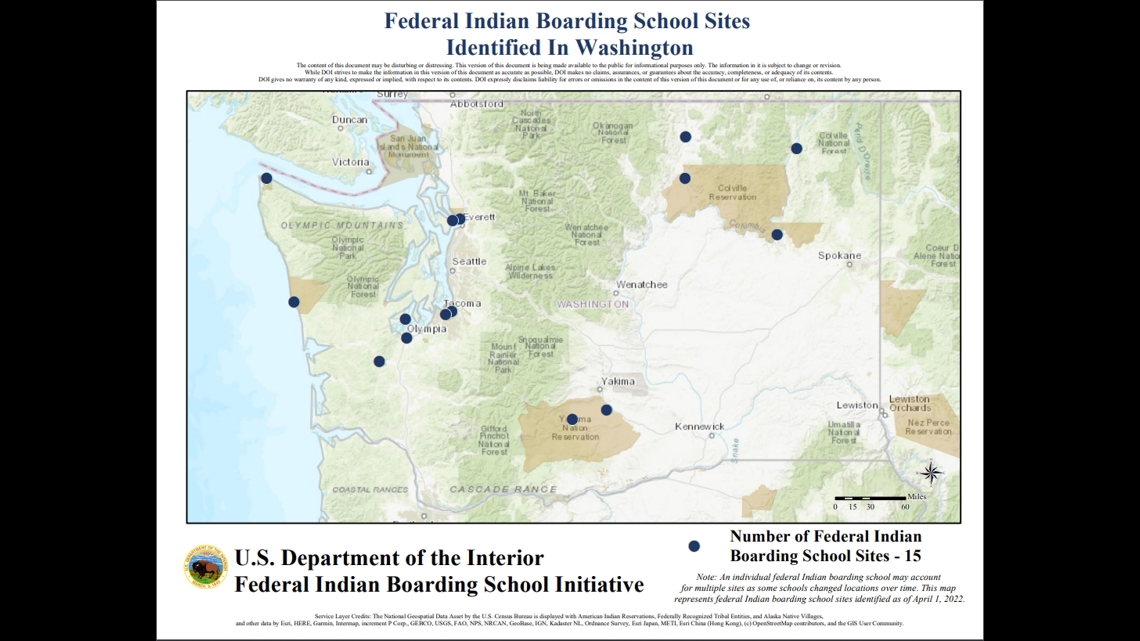

The website mentions the site hosted an Indian boarding school for more than 60 years, but there are no buildings or markings at the park recognizing that part of the fort’s history.

Jon Shellenberger, and the Yakama Nation, hope to change that.

Shellenberger is heading up what he calls a “dirty dozen” of volunteers, students, even cadaver dogs looking for evidence of the fort’s darkest past: gravesites of former students.

He’s been using ground-penetrating radar on the grounds of Fort Simcoe since 2021, and after scanning a couple of the 200 acres of park property, Shellenberger has not found any evidence of bodies buried at the park.

But he expects to find proof someday and hopes that will generate interest in adding a memorial, or interactive exhibit to the park.

”We know there was abuse of the children, and potentially even death as a result, we also know about all the disease,” said Shellenberger.

He works as an archaeologist with the state’s Department of Fish and Wildlife, but Shellenberger does the survey work during his spare time, with a $30,000 radar he said he purchased with his own money.

Shellenberger said grants have helped pay for cadaver dog teams and student researchers to assist with the search.

A Yakama Nation tribal member, Shellenberger, had ancestors who attended the school.

“They cut their hair, tried to break them down, their identity, who they were as a person,” said Shellenberger, who said he has identified 732 students forced to attend the school.

He estimates more than a thousand students attended the school at Fort Simcoe between 1860 and 1922.

Fire destroyed one of the buildings in the 1950s and the other was demolished before the property opened as a state park.

Shellenberger said the area of the park used for the school is marked “Lieutenant’s Quarters” on the signage at the property today.

He said publicly recognizing, even apologizing, for what happened on the property would help tribal members heal.

”I can’t help but to think that a lot of the problems in our community stem from this place, and it’s scary because there’s no trace of it,” said Shellenberger.

Jerry Meninick, former Chair of the Yakama Nation, and the tribe’s current Culture Deputy Director, is glad someone is trying to tell the park’s hidden past.

”Almost always have to remind the United States, and Washington state, that we’re still here,” said Meninick, whose father, uncles, and aunts attended Fort Simcoe.

He heard stories about students being taken from their homes, forced to cut off their braids, prohibited from speaking their native language, and punished when they tried to escape.

”It was a story of trauma. I don’t know that even now generations, that our people have ever gotten over that,” said Meninick.

Shellenberger said he was motivated to act after volunteers found hundreds of gravesites at Indian Boarding Schools in Canada in 2021.

He hopes to continue to use his radar to search grids of the park this summer and in October another dog team from Cairn Canine Detection will be on-site.

Shellenberger’s group hopes to present its findings to the Yakama Nation next summer in hopes of getting the tribe to work with Washington State Parks to find a way to honor the students who attended, and may be buried on the fort property.

He’d like to see a memorial or interactive exhibit at Fort Simcoe.

“It’s just something I can’t walk away from,” said Shellenberger.