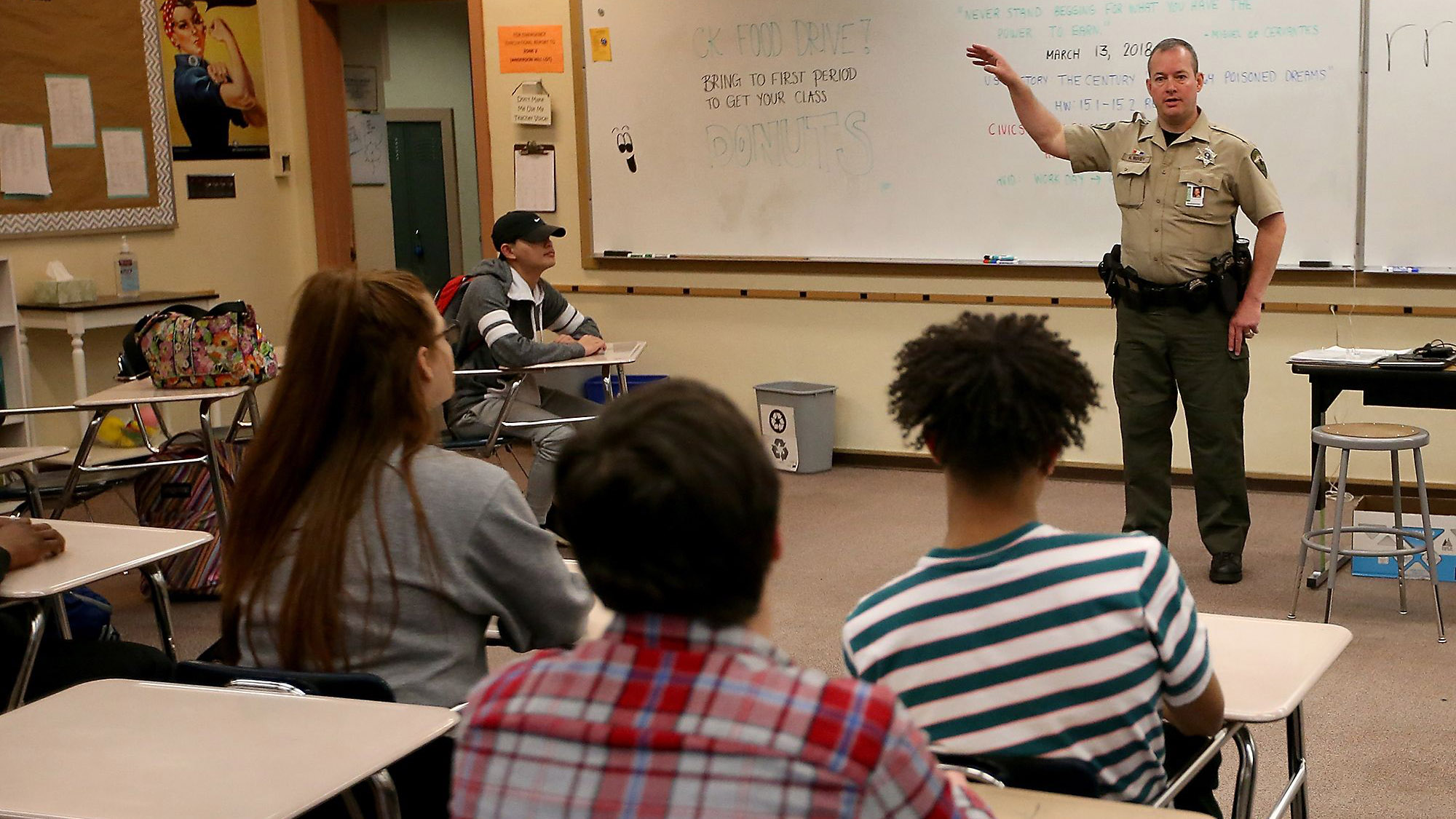

SILVERDALE — Students trickled into Katherine Devnich's civics class as usual on Tuesday, finding their seats, opening their books, chatting among themselves.

The class, at Central Kitsap High School, had hardly begun when co-principal Gail Danner came over the loudspeaker and announced, "We are going to begin a lockdown drill based on our ALICE protocol."

Immediately Devnich's students sprang into action, drawing the blinds and moving desks to block the doors.

ALICE stands for "alert, lockdown, inform, counter and evacuate." The focus of Tuesday's drill was barricading to deter an intruder, including the possibility of an active shooter.

Devnich coached her students in a calm voice as they waited in the dark for the “all clear.”

"We're just going to sit and hang out," she said, as the minutes ticked by. "Think about escape routes. Don't be super loud."

Students take active role in survival

Gone are the days when students are simply advised to hunker down under desks when there’s an active shooter or other intruder threat. Central Kitsap School District, like other districts, has moved to "options-based" training that shows staff and students how they can respond quickly and proactively to unpredictable and rapidly unfolding intruder events.

Flexibility is the key, said Joe Vlach, director of operations, who led the district to adopt the ALICE Training Institute's program three years ago. All Central Kitsap staff have now been trained. This year, the district is training students using age-appropriate materials and techniques.

While lockdowns remain the foundation of an intruder response, ALICE trainees learn about other options, including when and how to evacuate, and how to counter or deter an attacker. Countering could mean engaging the intruder to talk him down or distracting him by shouting or throwing objects. In extreme cases, staff may decide to rush an assailant.

Central Kitsap students will not be trained in countering, Vlach said.

While options-based response training has been around for nearly two decades, the 2007 Virginia Tech shooting escalated discussion of including students in the training, said Central Kitsap school resource officer Mark McVey, a Kitsap County Sheriff’s deputy.

Within 10 minutes, Danner came back on the loudspeaker. "This concludes our lockdown drill for today," she said. "Thank you very much for your participation. You may resume your regular classroom activities."

Drilling in other districts

The ALICE active shooter civilian response training is used in more than 4,000 K-12 schools nationwide, as well as colleges, hospitals, libraries, churches, businesses and government agencies. More than 4,000 police agencies have been trained in the protocol, according to the ALICE website.

North Mason and Bremerton school districts also use ALICE. North Mason started training students this year.

North Kitsap School District is in the preliminary stages of implementing ALICE. Training of administrators and teachers will begin in May. “We are also developing protocols on how to inform our students with age-appropriate materials,” said NKSD Superintendent Laurynn Evans.

Similar protocols include the Department of Homeland Security's "Run, Hide, Fight," which is used in the Bainbridge Island School District. Bainbridge High School students this winter received information on “Run, Hide, Fight,” as well as basic first aid during assemblies conducted with the Bainbridge Fire and Police departments. Parents of students at all grade levels were briefed on the training in meetings this winter.

South Kitsap School District’s lockdown drills “focus on flexibility and empowering staff to make decisions based on the event,” said spokeswoman Amy Miller.

Last year, South Kitsap added an administrator as director for safety, security and emergency management. The district this year used levy money to add security guards at the high school, and it recently posted two more roving security positions primarily for elementary sites. The district has contracts for two school resource officers, one each from the Kitsap County Sheriff’s Office and Port Orchard Police Department.

Miller said South Kitsap was a pioneer for the region in implementing a threat assessment protocol developed for Oregon’s Salem-Keizer School District with law enforcement, courts and other public safety agencies. Schools work with a network of agencies to head off incidents by identifying student threats to commit a violent act. Steps include determining the seriousness of the threat and developing intervention plans to protect potential victims and address underlying issues.

“It reaches beyond school violence to help prevent other potential student risks like suicide, alcohol and drug use, physical abuse, dropping out and criminal activity,” Miller said.

Vlach said he couldn’t speak to the difference between ALICE and other protocols. Central Kitsap, after researching the options, chose ALICE because it was a curriculum it could institute throughout the district and replicate over the years, Vlach said. The ALICE Training Institute offers ongoing support to schools, another plus in the district’s view.

Central Kitsap School District spent roughly $15,000 to implement ALICE. The cost covered materials and training, including associated staff costs. There is an annual cost of roughly $7,000 to train new staff and conduct refresher training.

History of ALICE

ALICE is not new. It was developed by a Dallas/Fort Worth area law enforcement officer and his wife, an elementary school principal, following the Columbine High School shooting in 1999. The program, which has evolved, was meant not only for schools but for people in any public setting where a shooting could occur.

The goal was to give school staff proactive survival strategies to use while waiting for law enforcement to arrive.

A 2014 FBI study, cited by the ALICE Training Institute, of 160 active shooter incidents between 2000 and 2013 showed most lasted two to five minutes. In most cases, it takes longer for law enforcement and emergency responders to arrive on scene.

In 13.1 percent of the incidents, the situation ended after unarmed bystanders “safely and successfully restrained the shooter,” according to the FBI’s report.

ALICE comes at mass shootings from the position that, despite society’s best efforts at prevention, there will be lapses in the system. The key is preparing individuals to respond especially before help arrives, founder Greg Crane said in an article on the ALICE website after the 2017 Sutherland Springs church shooting in Texas.

“We cannot rely on external systems to keep us safe. Yes — improvements to the system can help — but ultimately, individuals need to be trained and empowered to participate in their own survival with proactive response strategies,” Crane said.

“Every able-bodied person has God-given natural abilities that makes harming them with a gun very difficult. Every group of good people possess huge tactical advantages over the lone gunman,” Crane wrote. “These violent events are survivable, and people do have options.”

The ALICE Training Institute, in a press release, cited the Jan. 20, 2017, shooting at West Liberty-Salem High School in Ohio as an example. In the incident, one student who walked in on the 17-year-old gunman in a bathroom was shot multiple times but survived.

West Liberty-Salem Superintendent Kraig Hissong, at a press conference the day of the shooting, said ALICE training helped people evacuate the building safely. Hissong said staff and students used desks, brooms and other items to block the door before evacuating through the windows, WDTN-TV reported.

“We don’t want to scare people, but we want to be prepared, ‘What if? What could I do?’” Vlach told students on the day of the drill.

SRO McVey encouraged students to carry awareness of potential threats everywhere: to the mall, the movie theater, the public library.

“Don’t think of this as just in your classroom. Think of it as a life skill,” McVey said.

Psychological costs, benefits

Involving students in armed assailant response training has costs and benefits, the National Association of School Psychologists and the National Association of School Resource Officers noted in a joint statement issued in 2014 and updated in 2017.

“It is critical that participation in drills be appropriate to individual developmental levels and take into consideration prior traumatic experiences, special needs and personalities,” the statement says.

Participation should never be mandatory, the two groups advise. School mental health professionals should be involved in planning. Adults should monitor participants during the drill for signs of trauma and offer support afterward to anyone (including staff) who needs it.

Young children, special education students, those who have experienced trauma or who are English language learners are more likely to be upset by the training, Vlach said. Central Kitsap curriculum specialists reviewed and vetted the ALICE training methods and materials, including a book for younger grades, “I’m Not Scared … I’m Prepared.” Training activities are adapted according to individual needs in some cases.

Vlach said feedback he’s gotten from parents and students has been largely positive.

“I think the drill we did yesterday was informative,” said Central Kitsap High School senior Bradley Martel on March 14, the day students held a memorial for victims of the Parkland, Florida, shooting. “It makes me feel more aware and better prepared.”

“I think it helps because it shows they are trying to do something about the problem, but also I feel like it’s not enough,” said CKHS senior Riley Petoff.

The reality is, barricading a door may not stop an intruder, but it could slow them down, Petoff said. “At least we’re trying something, we’re trying to make a difference.”

In North Mason School District, Superintendent Dana Rosenbach said the rollout of training at Belfair Elementary caused concerns among some parents. The district is rethinking whether to use the “I’m Prepared” book. Vlach said the book has gone over well in Central Kitsap schools.

Preparing for the unthinkable

North Mason experienced an extended lockdown last spring triggered by what turned out to be a false report of gunshots. During the lockdown, staff deployed tactics learned during ALICE training, including barricading doors. One student told the Kitsap Sun his teacher encouraged students to grab items to throw at the intruder. Rosenbach said the incident helped the district refine its response strategy.

Available research supports the effectiveness of lockdown drills with options-based training, but more research is needed, the school psychologists and resource officers’ report states.

School shootings are rare, the report notes. Armed assailants in schools account for 1 percent of homicides among school-aged youth, and yet to refrain from training would be irresponsible, school officials say.

Rosenbach said she and her staff are sad the culture is such that drills for the unthinkable are necessary.

“It goes beyond frustrating that this is part of our everyday life,” she said. “Of course we hope we are not a place that has such an event. We can’t guarantee that it won’t happen. So we have to be able to respond in the best possible way.”