SEATTLE — Before students returned to the classroom this week, school districts across Washington were contending with growing budget shortfalls, with some school leaders blaming the state for not providing enough funding.

That’s despite a years-long legal fight that compelled lawmakers to produce more money for education.

To understand how we got here, we need look back more than a decade:

A constitutional obligation

Education funding in Washington state starts with the state constitution. Article IX, section 1 reads, ‘It is the paramount duty of the state to make ample provision for the education of all children residing within its borders, without distinction or preference on account of race, color, caste, or sex.”

Attorney Tom Ahearne took that sentence all the way to the Washington Supreme Court.

“Ample means not just adequate, considerably more than adequate,” Ahearne said.

For decades, schools complained they were underfunded by the state and filling the gaps with local tax dollars. That created an inequitable system where students in property-rich districts get a better education than those in poor districts.

Ahearne represented two families and a consortium of school leaders who accused the state of failing its constitutional obligation.

At the top of the lawsuit was the McCleary family.

Stephanie McCleary, an employee in the rural Chimacum School District, joined the legal fight when her son, Carter, was in the second grade.

“I went to his high school graduation before the case was over,” Ahearne said. “That’s how long this dragged on.”

The plaintiffs won the case before the Supreme Court, in what became known as 2012’s ‘McCleary Decision.’

The court fined Washington state $100,000 per day for more than five years.

It demanded the legislature come up with a plan to raise teacher salaries, reduce class sizes, and reduce the reliance on local taxes to fund schools.

“Our state constitution places a high, high premium on equality in that sense, and equity,” said Rep. Sharon Tomiko Santos, the chair of the Washington State Legislature’s Education Committee.

“The court basically said, when you have a school district that does that, the state is shirking its duty,” Santos said.

A new formula

In 2017, the state came up with a new formula that poured billions of dollars of new funding into education. The McCleary fines stopped.

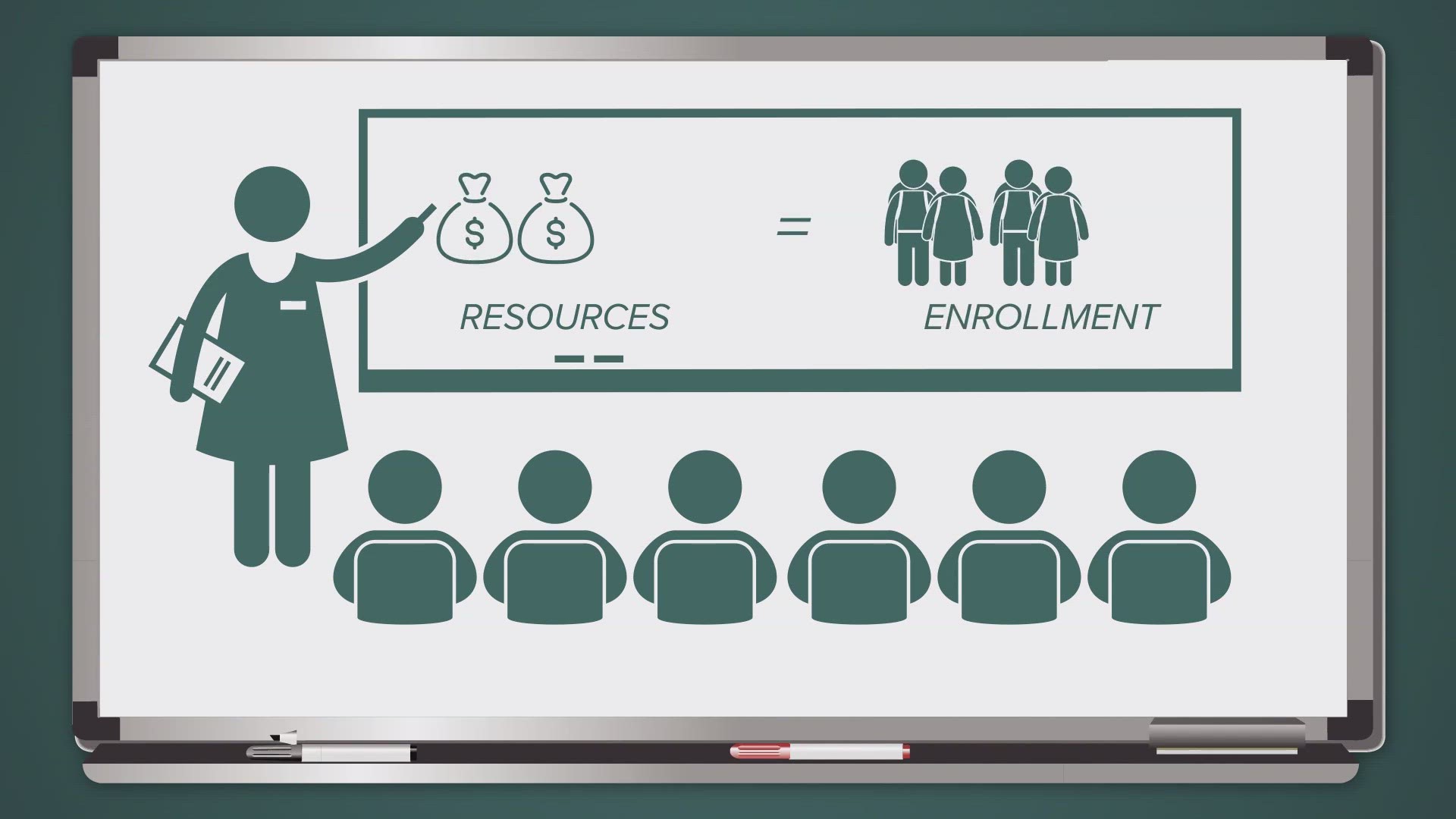

The formula, called the ‘Prototypical Model,’ sets standards for resources and staffing every school should get, and then adjusts that funding based on enrollment. The more students a school district has, the more money it gets.

School districts can still use local tax dollars, to a point, for extra programs or activities. The districts are required to report to the state how they are spending state dollars, but they don’t lose control over the spending.

“We send the money out, the way it gets spent is totally within the discretion of the local jurisdiction,” said Rep. Santos.

Room for improvement

State educators say this system is better.

“Pre-McCleary, it was always a struggle,” said Jared Kink, president of the Everett Education Association.

Kink co-chairs the Washington Teacher’s Association’s legislative strategy committee. He said after 2017, school districts started to see more consistency in funding, especially around salaries.

Average teacher salaries have risen to become the fifth highest of any state in the country.

Washington state is among the top 20 states for education spending per student, according to U.S. census data.

Union leaders say schools are still short of funds needed for transportation, paraeducators and federally mandated special education services.

“They have to use local dollars or state dollars in order to cover the requirement in special ed,” Kink said. “For that one-to-one para[educator], that gets really, really expensive quickly.”

In the 2019-2021 budget, state lawmakers allocated more than $27 billion for education, representing over half of the budget.

In the next budget cycle, education funding increased by more than a billion dollars, to $28.3 billion. But while the dollar amount increased, it represented a smaller share of the overall budget (about 48%).

“The overall dollars have gone a little bit up,” Kink said. “But that’s deceptive. Because the cost of things has gone up from everything from transportation to [the] cost of living.”

Declining enrollment has forced some districts to make difficult decisions, like consolidating schools in Bellevue.

“To close a school is shocking for a community,” Kink said. “It’s hard to recover.”

In a post-COVID world, state lawmakers are looking into how schools can be better equipped for the future:

“We know that learning can take place anytime, anywhere,” Rep. Santos said. “So how can we measure whether or not students are learning?”