SEATTLE — A new study published by researchers from the University of Washington and UC Irvine examines how COVID-19 spreads in different neighborhoods and it found the virus doesn't spread evenly through a community.

The study, published in September in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, factors in network exposure and demographics to simulate where and how quickly COVID-19 could spread through Seattle.

The study also looked at 18 other major cities.

Researchers used U.S. Census Bureau tract demographics, simulation techniques and COVID-19 case data from last spring to estimate a range of days for the virus to spread within a given city.

Researchers found some neighborhoods peak sooner than others, and in every city, the virus lingers far longer than some might expect, according to a write-up on the study by the UW.

“The most basic takeaway from this research is risk. People are at risk longer than they think, the virus will last longer than expected, and the point at which you think you don’t need to be vigilant means that it just hasn’t happened to you yet,” said study co-author Zack Almquist, an assistant professor of sociology at the UW.

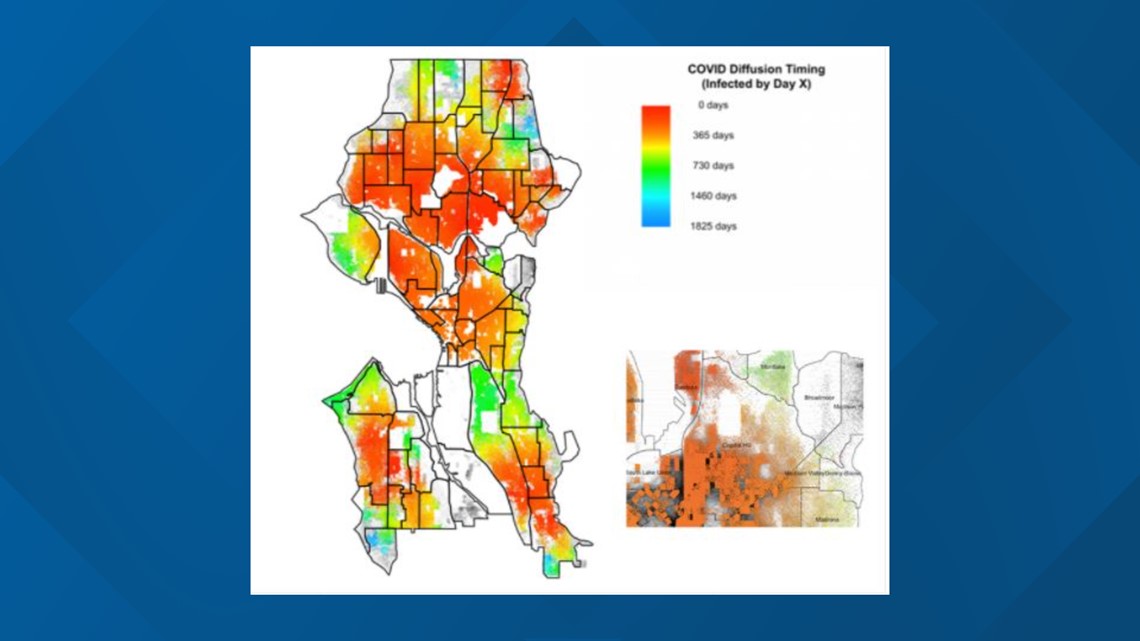

In Seattle, researchers discovered the overall range of the virus is vast, with some neighborhoods reaching their peak within 83 days, to others that take more than 1,000 days. The areas reaching their peak infection rate faster are shown in red in the map below. The areas in green are around 730 days, and the areas in blue are over 1,000 days. These estimates are assuming there is no significant intervention to stop the spread of the virus, such as a vaccine.

The study found denser Seattle neighborhoods, like Capitol Hill or the University District, reach peak infection rate earlier, while nearby neighborhoods, such as Montlake, won't reach their peak infection until weeks or even years later.

Researchers said these more detail-oriented models used for this study predict more "burst-like" behavior of the coronavirus' spread than standard models. Those models often take a high-level approach to a geographic area, like a county or state, and forecast based on a general idea that a virus will take root and spread at an equal rate until it reaches its peak infection.

“If you project these models for what it means over the country, we might expect to see some areas, such as rural populations, not see infection for months or even years before their peak infection occurs,” Almquist said. “These projections, as well as others, are beginning to suggest that it could take years for the spread of COVID-19 to reach saturation in the population, and even if it does so it is likely to become endemic without a vaccine.”