MONROE, Wash. — Governor Jay Inslee signed an order earlier this week to release nearly 1,000 non-violent offenders from Washington prisons to help slow the spread of the coronavirus within those facilities.

Columbia Legal Services, who are suing the state, said the governor’s order does not do enough to protect those incarcerated.

Demonstrations were held at the Monroe Correctional Complex, and the state capitol demanding the release of more Washington state inmates.

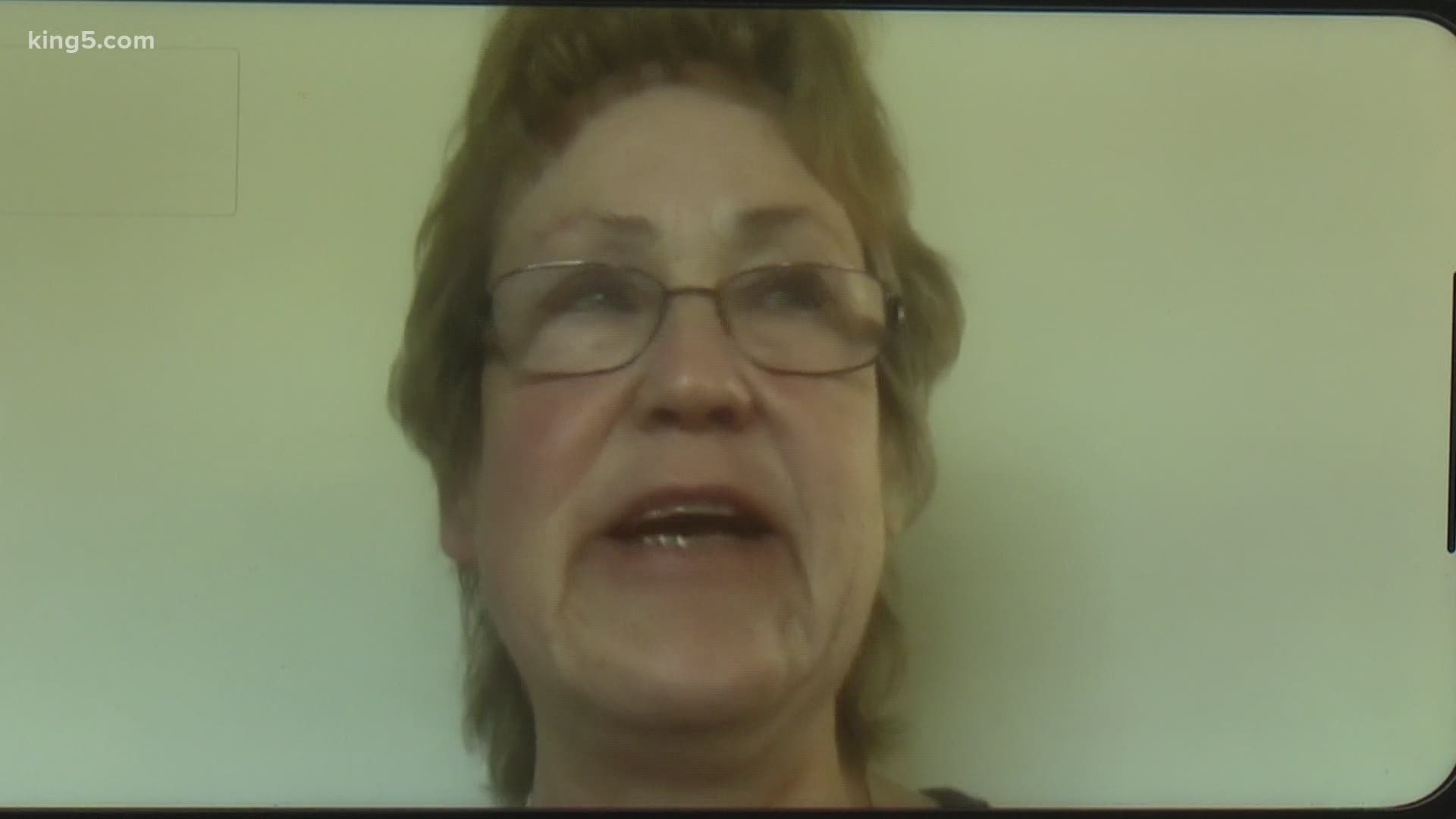

The idea of releasing more inmates has people like Sue Harms, terrified.

“Right now, I’m just shaking. I haven’t been able to sleep,” she said.

In 2004 Harm’s ex-husband, William F. Jensen was sentenced to four counts of conspiracy to commit murder for hiring a hitman to kill her, her sister and her children.

“He is currently in Monroe. He is at the age of 63 and he’s in extremely poor health,” Harms said.

She fears that since Jensen meets the criteria for age and health, he could be released.

The governor’s order specifies that those being released must be in prison for non-violent offenses.

“The class of prisoners being released just aren’t enough to effectively deal with the public health issues,” said Jeremiah Bourgeois.

Bourgeois spent 27 years behind bars for a violent crime and was released six months ago on parole.

He spoke at Columbia Legal Services’ press conference today on behalf of those behind bars.

Columbia Legal Services filed a lawsuit asking for the release of inmates in Washington prisons that are vulnerable to the virus.

The criteria are for those who are over 50, those with certain medical conditions, who are pregnant or have compromised immune systems, or those who have 18 months or less remaining on their sentence, and those on work release would

Bourgeois said this should apply for non-violent and violent offenders, so long as they are deemed unlikely to commit another crime.

“It’s not only the view of Columbia Legal Services but many people in the community that there are a large number of people in prison who don’t pose a risk to public safety and who could be released in order to deal with this public health issue and not jeopardize the risk of the community,” he said.

Jeremiah said the decision to release an inmate should be based on the likelihood of recidivism not the nature of their crime.

“After spending 27 years in prison I can assure you, if they think you pose a risk to somebody’s safety, you are never getting out of there,” he explained.

Harms believes the safety of victims and the public should come before the release of those incarcerated.

“There was a reason they were put in prison in the first place. There was a reason he was given 60 years. This man is dangerous,” she said.