SEATTLE — King County leaders unveiled a $1.25 billion behavioral health plan Monday aimed at increasing residential treatment beds and bolstering its workforce.

The plan would create a network of five crisis care centers, provides funds for the recruitment and retention of community behavioral health workers and boosts the number of residential treatment beds.

It would be paid for with a nine-year property tax levy that must be approved by voters. The levy would cost homeowners of a median-value home about $121 in 2024, according to the King County executive’s office. It would continue through 2032.

The King County Council is expected to vote on the proposal in February. If approved, the tax levy would appear on the April 2023 ballot.

Under the plan, the new regional crisis care centers would offer walk-in access and possible short-term stays to help people stabilize. One center would specifically serve youth. Until these centers can open, the county plans to use the tax revenue to fund mobile or site-based crisis behavioral health services.

Since 2018, there has been a “dramatic” loss of residential treatment beds across King County, dropping from 355 beds to 244 beds in four years, according to the county. The plan aims to “preserve and restore” these beds.

Finally, the proposal would create apprenticeship programs and access to higher education, credentialing, training and equitable wages to support behavioral health workers.

Providers say the county’s ability to respond to behavioral health crises in King County is itself in crisis.

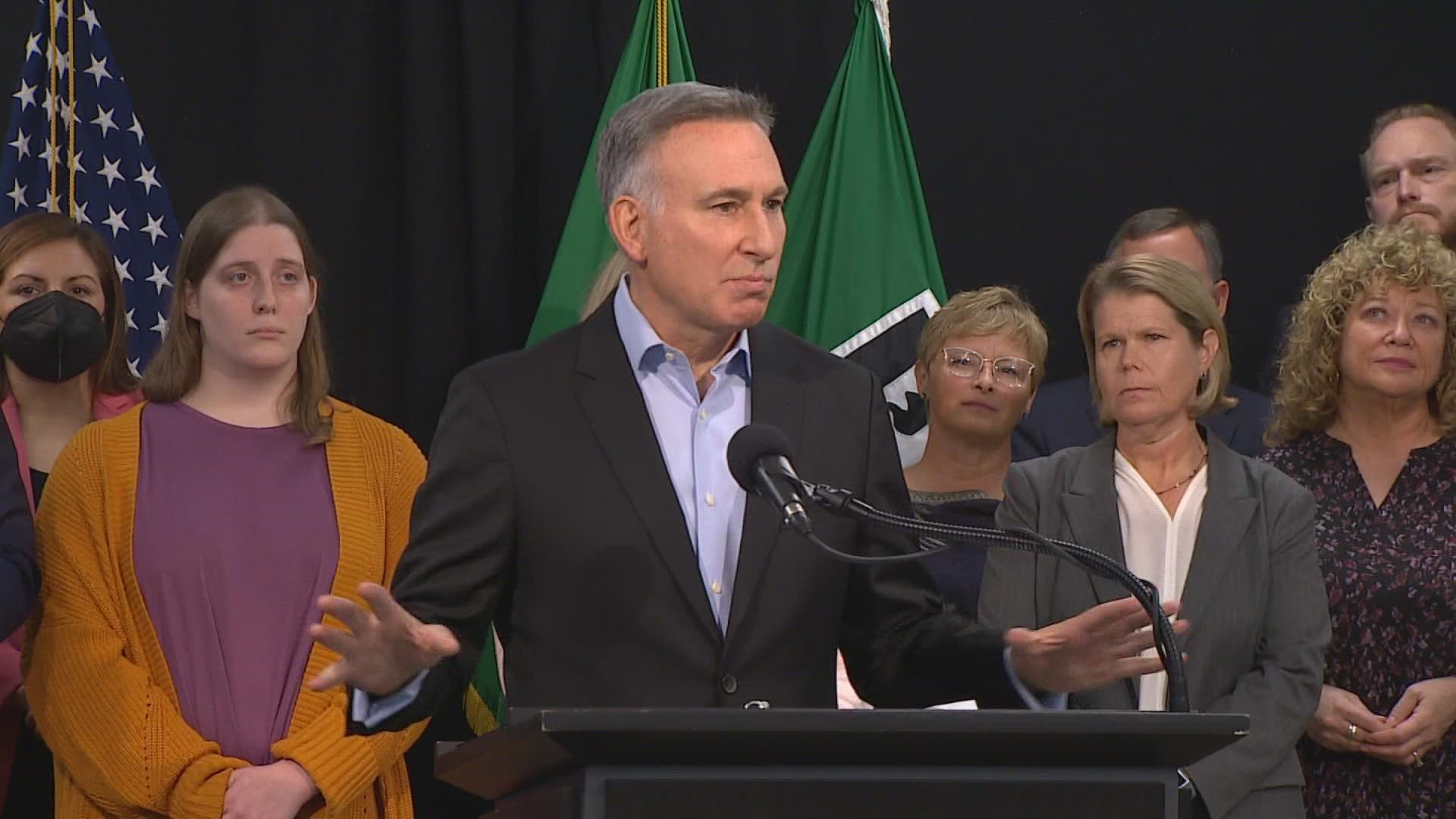

“The behavioral health system in this state has long been underfunded and underappreciated,” King County Executive Dow Constantine said in a statement. “The pandemic added further stress, and need is increasing even as we lose both treatment beds and qualified workers.”

There currently isn’t a walk-in behavioral health urgent care facility in King County, and there is only one 46-bed behavioral health crisis facility for the entire county. Downtown Emergency Service Center’s crisis solutions center, which is the county’s only voluntary crisis facility resource, requires a referral due to limited capacity.

In July, people waited an average of 44 days for a mental health residential bed, according to the county.