SEATTLE — In recent years, immunotherapy has been one way to target pediatric cancers, and clinical trials happening in Seattle are showing promise.

Right now Seattle Children's Therapeutics is conducting nine clinical trials for pediatric cancer immunotherapy at its Building Cure research facility, located on Terry Avenue in Seattle.

The month of April marks Seattle Children's 500th patient to participate in an immunotherapy trial.

About ten years ago was when another patient, Greta Oberhofer, turned to Seattle Children's while battling an aggressive form of leukemia. She was only three months old when she was diagnosed. Her family tried everything, from chemotherapy to a bone marrow transplant.

"During the transplant, she didn't fare very well. She became really sick," said Maggie Oberhofer, Greta's mother.

Then her cancer returned after her first birthday.

"We were definitely at that point where it was either hospice care or finding something revolutionary to try," said Maggie.

The Portland family turned to Seattle Children's for that revolutionary, last resort: immunotherapy.

Now, immunotherapy research at Seattle Children's is being developed on the 12th floor of the Building Cure Center, known as the Cure Factory.

"It's a floor that is set up to basically be a bio factory for making actual products for children that we are developing through our research programs," said Dr. Michael Jensen, who serves as Vice President of Seattle Children's Therapeutics.

Their lead program, known as "chimeric antigen receptor," or CAR T-cell immunotherapy, genetically engineers the body's immune cells and basically teaches them to attack cancer cells.

"In the last ten years, there has been an explosion in how we understand how the immune system and cancer interact," Jensen told HealthLink.

Immunotherapy works by educating T-cells in the immune system to recognize cancer cells as bad and destroy them, just like how they would recognize an infection.

"These T-cells are reacting to the cancer like it is a flu virus if you will. So they get very revved up," Jensen said.

Unlike chemotherapy and radiation, which are notoriously difficult with potential long-term effects, the side effects of immunotherapy are flu-like symptoms, according to Jensen.

For Greta, it was a high fever that was monitored by hospital staff as she received her immunotherapy.

"It meant that the T-cells were really aggressively attacking her cancer," Maggie said.

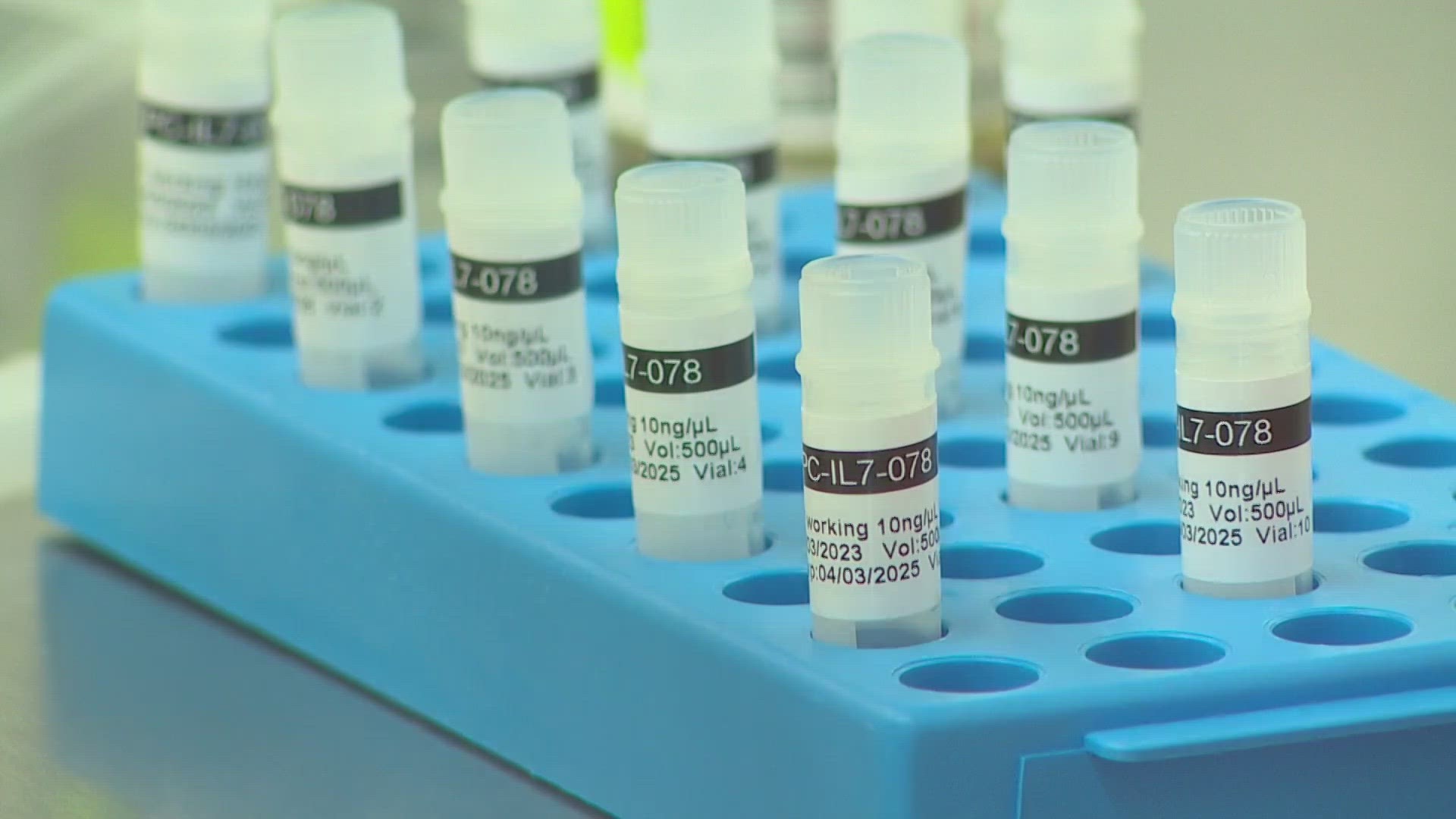

At the Cure Factory, T-cells from a patient's blood sample is extracted and altered to get them to target those cancer cells. Seattle Children's is working with hospitals across the U.S. to conduct these clinical trials.

"The child stays at {their} home hospital. The blood specimen is collected there. It basically gets shipped here, we make the product here, and then we freeze the product in suspended animation if you will, and then the tubes of the product fly back to that hospital," Jensen said.

Greta was among the first patients to be part of Seattle Children's early trials. That was nine years ago and now, she has been in remission and is a healthy ten-year-old fourth grader whose favorite subject is math.

Her mother Maggie said she is grateful for the life-saving treatment.

"So much has changed and we just are so lucky that this worked for us," Maggie said.

For information on how to be a part of any of these clinical trials, visit seattlechildrens.org/therapeutics.