PUYALLUP, Wash. — Earlier this month, the City of Puyallup decided to wait before approving a clinic designed to treat those struggling with opioid addiction.

During its Dec. 5 meeting, the city council unanimously voted for a six-month moratorium on setting up clinics outside the city’s designated medical zone.

City Attorney Joe Beck said a potential loophole in the city’s zoning laws was found that could undermine a 2016 city council decision on where these clinics could go.

“It just freezes things,” Beck clarified. “It doesn’t mean that this entity will ultimately not be able to be sited where they are, that’ll be up to council down the road.”

Beck said a public meeting about this will be scheduled sometime within the next two months.

Brave and Unbroken founder Pennie Saum, who advocates bringing more resources and wraparound services into Puyallup, said the city council’s announcement is a step backward for the city.

“For every dollar that we spend on methadone treatment, it saves up to three dollars in law enforcement costs, so it’s a huge impact,” she said. “For our city, in general, it would be significant to our community to be able to have these clinics for people to have access to.”

Right now, Pierce County has five opioid treatment centers that offer both counseling and medical services. None are in Puyallup.

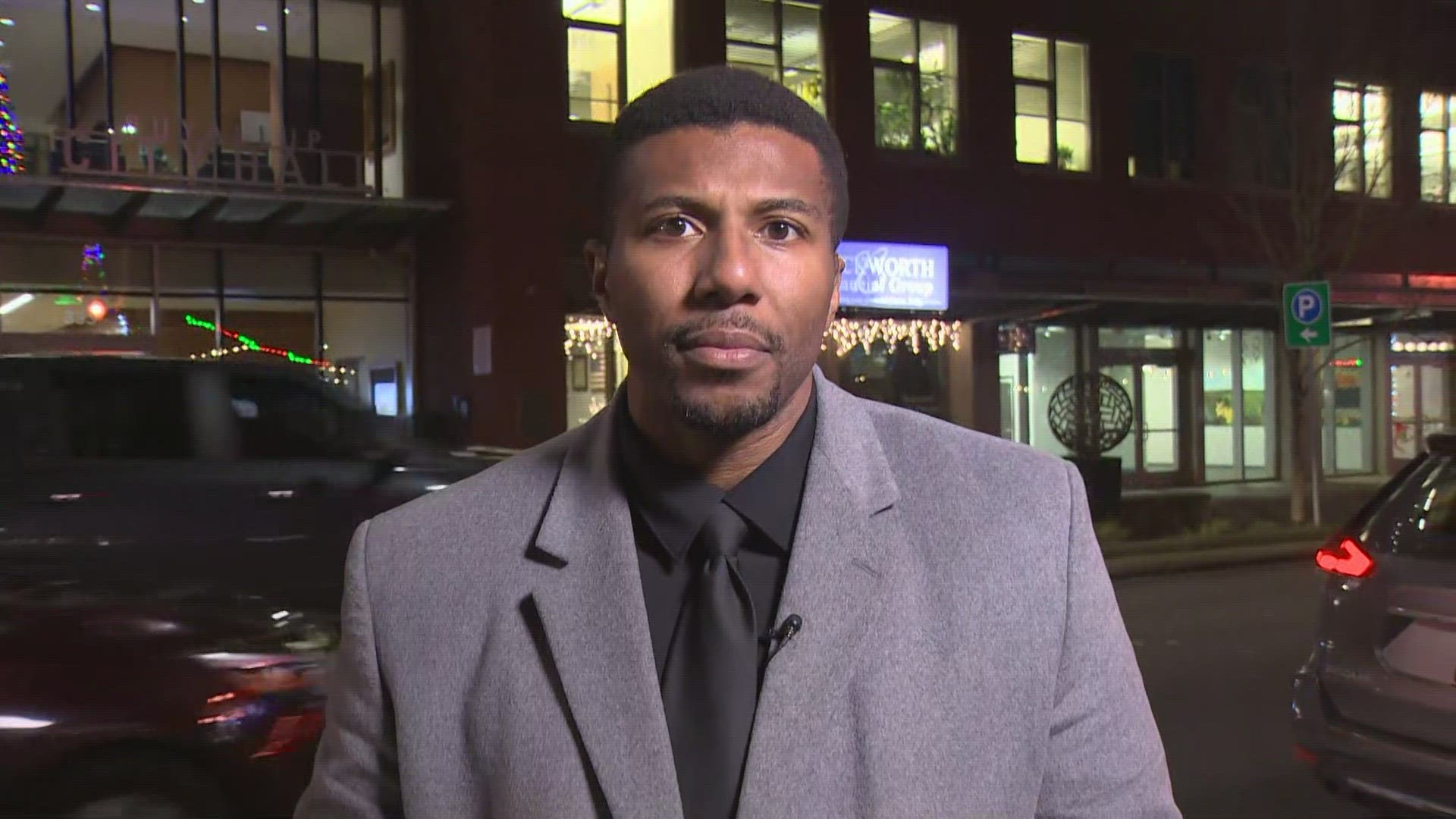

Certified Peer Counselor Kenneth King helps connect people to those services, but he said Puyallup’s current regulations keep them separated, making them harder to reach.

King said this can force some out of Puyallup to seek treatment, which city Councilmember Robin Farris admits can be another challenge.

“We don’t have a lot of really good bus service,” she said during a Dec. 5 city council meeting. “That’s another story in and of itself, it’s very difficult for people in Puyallup to get out of Puyallup.”

While King said there are clinics that sit outside the city limits, he hopes Puyallup will be opened up so residents have easier access to drug treatment.

“If we don’t have something here that at least acts as an access point, they won’t ever look for it,” he said. “It also kind of increases the stigma of it. Like, if we’re not allowing it here, why are we not allowing it here? It must be bad.”