SEATTLE — The 2001 Nisqually earthquake was a wake-up call for disaster preparedness, but it also provided valuable lessons for scientists studying earthquakes.

The magnitude 6.8 earthquake struck about 11 miles north of Olympia on Feb. 28, 2001 at 10:54 a.m. It was more than 35 miles underground, so there are no cracks or evidence in the Nisqually Delta today that it happened.

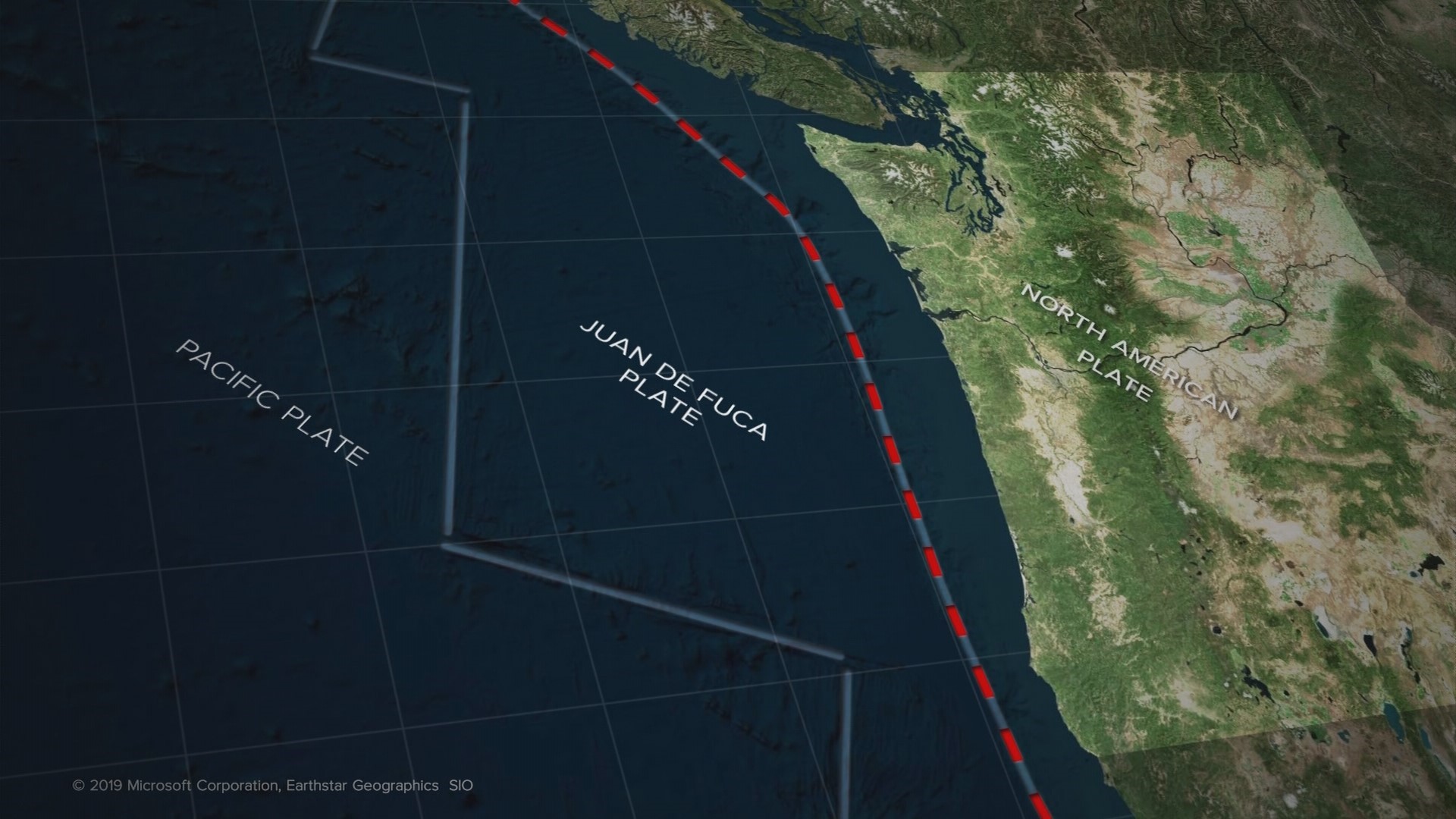

There are three types of earthquakes Washington faces, all of which are tied to the collision of crustal plates. That’s where the Juan de Fuca plate is slowly pushed under the North American plate into the Earth’s mantle.

Just off the coast is where the first kind occurs: Great earthquakes that happen hundreds of years apart, such as magnitude 9 earthquakes out of the Cascadia Subduction Zone.

The second kind is very deep – some 60 miles down. These “silent” earthquakes last for weeks and even months. Scientists say the leading edge of the plate becomes like taffy, slowly stretching every 14 months or so. However, they are so slow, they don’t do any damage.

Our most frequent damaging earthquakes come from the Benioff Zone, which is where the Nisqually earthquake originated.

Since the epicenter of the Nisqually earthquake was near Olympia, it wasn’t surprising that Olympia was hit hard with damage.

There was also major damage in Seattle, including destruction from liquefaction, which is when moist, sandy soil turns to a liquid consistency due to violent shaking. This happened in places like Boeing Field, where the soil lost the ability to hold up runways and buildings.

However, Tacoma, which was closer to the epicenter than Seattle, saw little damage.

“Tacoma was kind of in a shadow, where it didn't get the strongest intensity shaking. That was kind of thrown toward Olympia and north toward Seattle,” said Bill Steele, a seismologist with the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network.

The patchwork of severe damage revealed how different soils and rocks can lead to varying levels of impact.

Scientists set out a new generation of seismometers not long before the Nisqually quake struck. These instruments could record strong shaking, giving scientists a new tool to help analyze what happened.

“You get a pretty good picture of how the ground shook during the earthquake,” said Steele.

The Nisqually earthquake wasn’t unexpected, and scientists know another one is coming.

The Puget Sound region has experienced two other major quakes in the last 70 years – a magnitude 6.5 in 1965 and a magnitude 7.1 in 1949. The 1949 quake killed eight people, and the 1965 earthquake was blamed for seven deaths.

The Nisqually earthquake injured about 400 people. However, nobody died as a direct result of falling bricks or debris. A heart attack victim was the only fatality associated with the quake. Damage estimates were placed at several billion dollars.

Scientists said there was an 84% chance of another one like these in the 50 years following Nisqually. Since 20 years have already passed, does that mean the odds go up over the next 30 years? Washington state seismologist Harold Tobin said it’s not that simple.

“I can’t say because 20 years have passed that it’s now 86% or something like that,” Tobin said. “Let’s just call it more likely than not.”