Washington special ed students traumatized by physical restraints at school

A KING 5 investigation found cases in school districts across Washington state where special education students experienced significant psychological and educational setbacks due to being physically restrained and isolated.

'School Ruined Isaac's Life'

Heidi Stuber said she knew something wasn't right with her son Isaac soon after he started third grade.

Every time Stuber attempted to hug Isaac, who was 9 at the time, the once-affectionate child pulled away and screamed.

"It was very hard as a parent to see that my son had been so mistreated that he couldn't connect with the people who loved him in normal ways," Stuber said.

Isaac, who has autism, stopped completing classroom assignments. He refused to go to sleep on Sundays because he was afraid to start a new week at school. He slept on Stuber's bedroom floor for about two years because he couldn't get through the night without having a nightmare.

Stuber said her son’s actions stemmed from his experience at B.F. Day Elementary School in Seattle. School records show B.F. Day educators physically restrained Isaac repeatedly in 2014 as a means to control his behavior.

"It completely derailed his school career," Stuber said. “School ruined Isaac’s life.”

Isaac refused to enter any school building for two school years after his experience at B.F. Day. A University of Washington psychologist said the repeated physical interventions led Isaac to suffer from intense anxiety and trauma. Now, four years later, the 13-year-old only attends school part time because he says he’s still haunted by memories of being restrained.

“I try to block those memories out,” Isaac said, adding that he didn’t want to talk about what happened to him in third grade.

Under a 2015 state law, educators are allowed to restrain and isolate students only when there’s an imminent likelihood of serious harm.

In the 2016-2017 school year, Washington school districts reported 33,268 restraint and isolation incidents involving 6,720 students. In some cases, individual students were either restrained or isolated dozens of times. No state agency tracks whether the state’s local schools are using it appropriately.

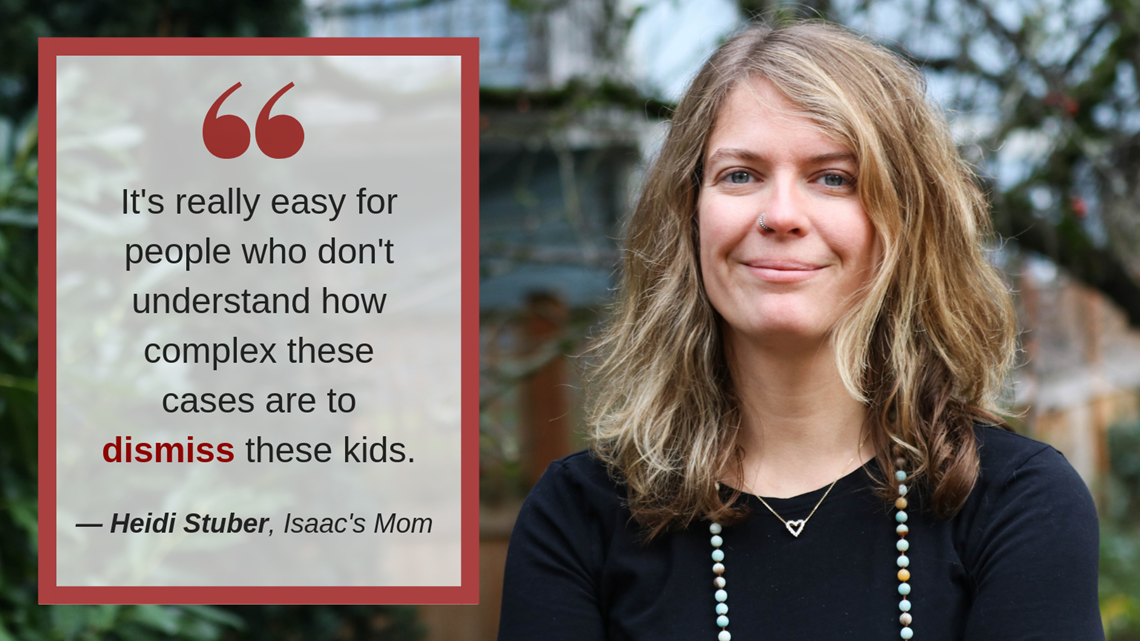

“It’s really easy for people who don’t understand how complex these cases are to dismiss these kids and say they’re bad kids or they did something to deserve it,” Stuber said. “They didn’t.”

School officials and parents don’t always agree on whether physical restraint and isolation is justified in individual cases. But regardless of the reason why educators use isolation and restraint, the research is clear: there’s no educational value to the practices, and for some kids, the intervention techniques cause lasting trauma.

“There’s no question in any of the professional fields that the use of restraint and isolation is damaging to children,” said Jeannette Cohen, a long-time special education attorney who represented the Stuber family in their legal case against Seattle Public Schools. “I think they feel violated when they’re grabbed. I think they feel diminished as people. I think they feel like their issues are not taken seriously. I think they feel blamed that the behavior is someone how intentional and their fault, and I think that’s a blame that they carry with them.”

A KING 5 investigation found multiple examples in districts across the state where students with disabilities, like Isaac, experienced significant psychological and educational setbacks after they were repeatedly restrained or isolated in schools.

Braedon Hafey, a 7-year-old Tumwater student with autism, began to injure himself at home and at school after teachers locked him in a closet-sized room dozens of times to control his behavior. His mom Kris Hafey says he started pounding his head against the wall and biting himself whenever she told him to complete a simple task.

Tumwater teachers isolated the student at least 56 times during the 2016-2017 and 2017-2018 school years, according to a KING 5 analysis of Braedon’s isolation reports. Staff sent him to the isolation room six times in one day in January 2018. In response to his self-injurious behavior, Braedon’s mom temporary pulled him out of school.

River Willison, an 11-year-old student with autism, refused to attend school full-time for about three years because the use of isolation and restraint in the Bellingham School District psychologically traumatized him.

During a six-day period in second grade, River was either isolated or restrained seven times. In one incident, school officials documented that the intervention lasted three-and-a-half hours.

River became so afraid of school that he threatened to kill himself on the first day of third grade. His mother Erin Willison said he overheard her planning his upcoming curriculum with a school official on the phone. He ripped the doors off the hinges, punched holes in the walls, and then he ran outside and threatened to jump in front of a car.

He was subsequently hospitalized three times, including two, 6-week stints at a behavioral health outpatient treatment center in Florida.

Local special education experts say teachers often default to using restraint and isolation as a way to control behavior that should instead be addressed with different techniques.

Cohen, the special education attorney, said she routinely hears educators classify student behavior as dangerous when it’s not.

“I think it’s perception,” Cohen said. “I think they get caught up in a situation where they don’t know how to respond, and they do the best they can.”

She and other special education experts blame the problem on a lack of training and a special education system that’s underfunded statewide by millions of dollars. They say the state legislature has never set aside enough money to fully fund the specialized professional development and resources teachers need to address problematic behaviors in alternative ways, such as using a method called positive behavior support.

It’s an issue that has left many educators frustrated, with their hands tied and without options to adequately meet the individual needs of students with disabilities, as federal law requires.

Isaac's Story

Like many children on the autism spectrum, Isaac struggles with sensory issues. He has a difficult time with transitions, and he can’t read social cues, like body language.

Prior to attending B.F. Day, Heidi Stuber said Isaac had some issues “with opposition.” He occasionally had meltdowns and sometimes refused to do his schoolwork. But she said he was a happy, “bubbly” kid, who — most of the time — was able to attend class and have positive relationships with school staff and peers.

“I used to get out and do a lot of stuff and now I’m kind of more of a hermit,” Isaac said. “(I) play Minecraft all day or other video games, um, stick inside. Don’t really leave the house much.”

Stuber said her son, who currently sees a therapist to help him cope with anxiety and trauma, became emotionally disturbed and depressed after attending B.F. Day.

Isaac’s meltdowns happened more often, she said, because his brain was quickly triggered into a “fight or flight pattern.” Stuber said he started to get “jumpy” around unknown adults, and he became especially suspicious of school staff because he lost trust in their ability to care for him.

“There was an innocence in him that was lost,” she said. “I don’t think he’ll ever get it back.”

Isaac attended a self-contained special education classroom at the elementary school. Over five weeks in 2014, B.F. Day staff documented seven days where educators grabbed Isaac and restrained him — sometimes several times in a day. The behaviors documented in school records appear to be dangerous, at least in the way educators described them. In one incident, for example, Isaac ran away from school and stepped in front of a car on Fremont Avenue North. In another incident, Isaac began striking school staff, according to the records.

But Stuber said it’s what the records don’t show that troubles her the most. She says Isaac was restrained for other behaviors that weren’t dangerous. Those incidents, she said, weren’t documented as state law requires.

Stuber witnessed two incidents herself, she said, and she kept her own list of suspected incidents that she says school officials never reported in writing. She said Isaac was restrained for making a mean face, hitting a door and throwing a pencil on the ground.

In 2015, Stuber testified before state legislators in Olympia about the harmful effect that restraints had on her son. She urged them to pass the law that limits how educators can use restraint and isolation in schools.

In May 2015, Gov. Jay Inslee signed House Bill 1240 into law, and Isaac was front and center to witness it.

Isaac Attends Bill Signing

That same month, Stuber and other parents in Isaac’s self-contained classroom sent a letter to Washington’s Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI), asking for help.

They reported a “significant and deeply troubling increase” in the use of physical restraint and isolation on students at the school. They wrote that it often occurs “without the legally required written reporting after the incident.”

Under state law, school districts must make a “reasonable effort" to verbally notify parents within 24 hours after using restraint and isolation on a student. And within five business days, school staff must send written notification to the families.

Restraint, Isolation Persists At B.F. Day

In 2016, and again in 2019, Isaac’s family settled their cases against Seattle Public Schools in agreements that cost the district thousands of dollars. But the use of restraint and isolation continues at B.F. Day.

“I thought things would change more than they did,” Stuber said.

This school year, Gina Bunster said she walked into B.F. Day and witnessed the special education teacher restraining her son Alec on two separate occasions.

Bunster learned that Alec, a 6-year-old diagnosed with autism, was restrained for running out of his classroom and into another part of the school building.

She said officials never documented the incidents she witnessed, and she believes this failure to document them means she will never know how many times it happened in total. But she does know her son started to become anxiety-ridden as a result.

“There was something that changed. The love for learning became quashed in him,” Bunster said. “He didn’t even want to leave the house. He wanted to stay home.”

The latest data reported to OSPI shows that B.F. Day Elementary School uses restraint more often than most other Seattle public schools.

Last school year, most Seattle public schools reported less than five restraint incidents to the state. B.F. Day Elementary School reported 63 restraint incidents — more incidents than all but two of the 109 Seattle public schools that reported data. Northgate Elementary reported 88 incidents — the district’s second highest number. Gatewood Elementary reported 140 incidents — the most of any school in the district.

B.F. Day ranked high on the district's list of restraint incidents in the 2016-2017 school year, too. The elementary school documented 75 separate incidents of restraint that year. No other school in the district came close to that number, with the exception of Northgate Elementary School, which reported 132 restraint incidents that school year.

“The fact that it’s still happening—that kids are still being restrained or isolated—to me is just shocking and wrong,” Cohen, the special education attorney, said.

District Response

Tim Robinson, a spokesman for Seattle Public Schools, said B.F. Day staff comply with state law and are “diligent” in reporting any use of restraint to parents and to the district.

“The emotional, mental, and physical well-being of our students in our highest priority. Isolation and restraint are used as a last resort, and only when student behavior is likely to result in serious harm,” he wrote in an e-mail to KING 5.

Robinson declined to respond to specific allegations made by the Stuber and Bunster families.

He added that B.F. Day is one of seven schools in the district that provides intensive services to support students with unique behavioral needs.

He said the district provides ongoing crisis prevention and intervention certification training to special education staff. The techniques, he said, stress de-escalation strategies to reduce and avoid the use of restraints and isolation.

Stuber said Isaac has worked hard in the last few years to be able to return to school.

He now attends Seattle’s Jane Addams Middle School for a portion of the school day. But Stuber said he continues to be triggered by school-related activities, educators and unfamiliar adults.

The mother’s biggest fear, she said, is that Isaac won’t graduate from high school.

“He’s lost his identity as a learner,” Stuber said. “He doesn’t see himself as a student or a kid who goes to school.”

Resources And Support

If Your Child Has A Learning Disability

Know your rights. The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction offers guidance for families, which includes a handbook with information about you and your child's rights under state and federal law.

If you have questions about the special education process or difficulties communicating with your school district and need additional help, OSPI has special education parent liaisons available to assist you.

The state also has education ombuds who work with families to answer questions and help resolve concerns. Contact their office online or by phone at 866-297-2597

About This Series

This story is the eleventh part of "Back Of The Class," a multi-part investigation into the state of special education in Washington. The series exposes the reasons why Washington lags behind much of the country in serving one of our most vulnerable populations: students with learning disabilities.

Part 2: Washington kids with disabilities often denied right to learn in general education classrooms

Contact The Reporters

Susannah Frame is the Chief Investigative Reporter at KING 5. Her stories have exposed many wrongs, leading to changes in public policy, congressional investigations, federal indictments and new state laws. Follow her on Twitter @SFrameK5 and like her on Facebook to keep up with her reporting. For story tips or questions, e-mail her at sframe@king5.com.

Taylor Mirfendereski is a multimedia journalist, who focuses on in-depth reports and investigations for KING 5's digital platforms. Follow her on Twitter @TaylorMirf and like her on Facebook to keep up with her reporting. For story tips or questions, e-mail her at tmirfendereski@king5.com.