Fight for special ed services leaves Washington families financially devastated

As families push to get their children with disabilities the resources they need to succeed in school, some school districts dig in their heels.

Eleven-year-old River Willison burst open the door after school one January afternoon to find his mother overwhelmed.

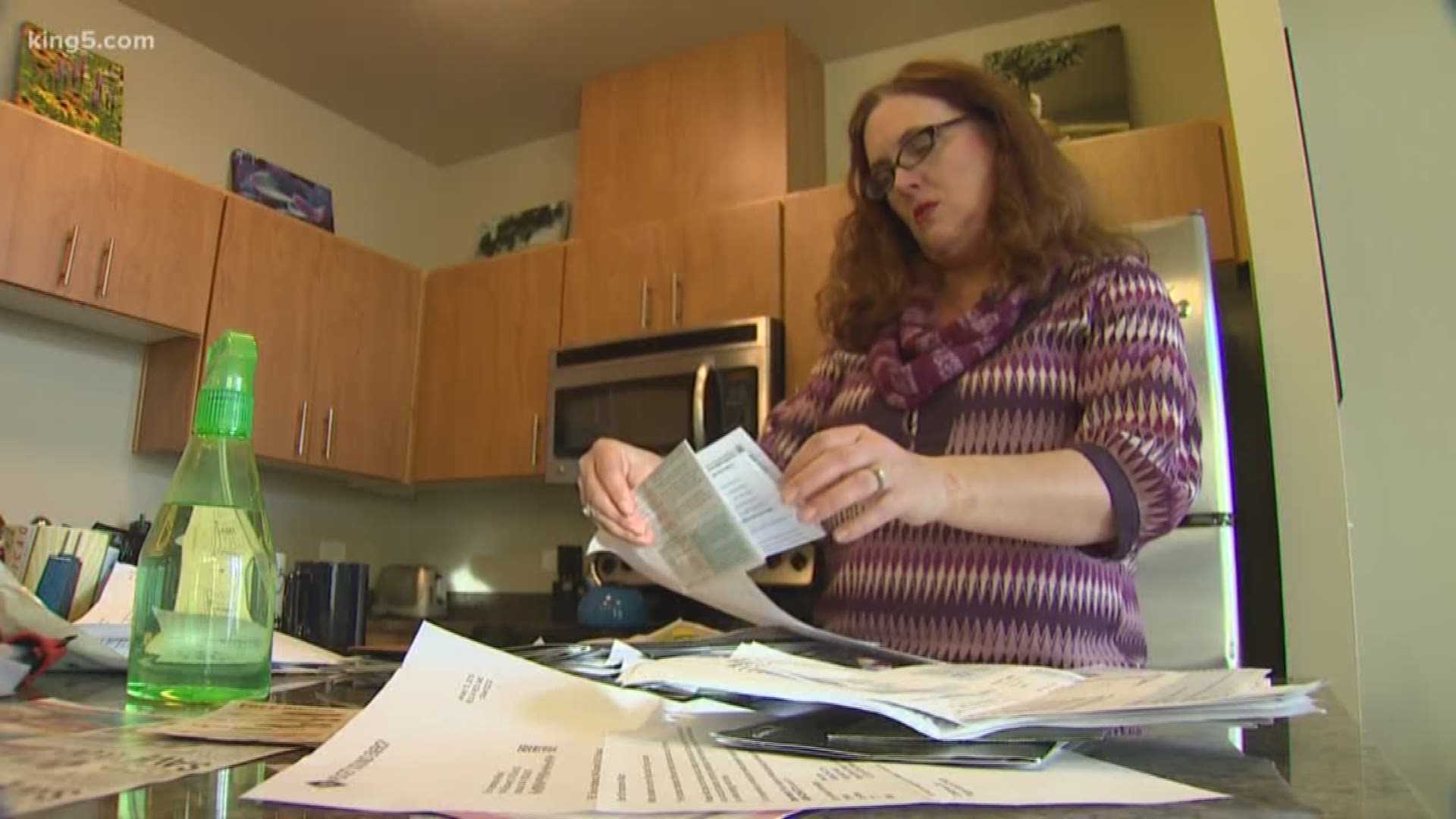

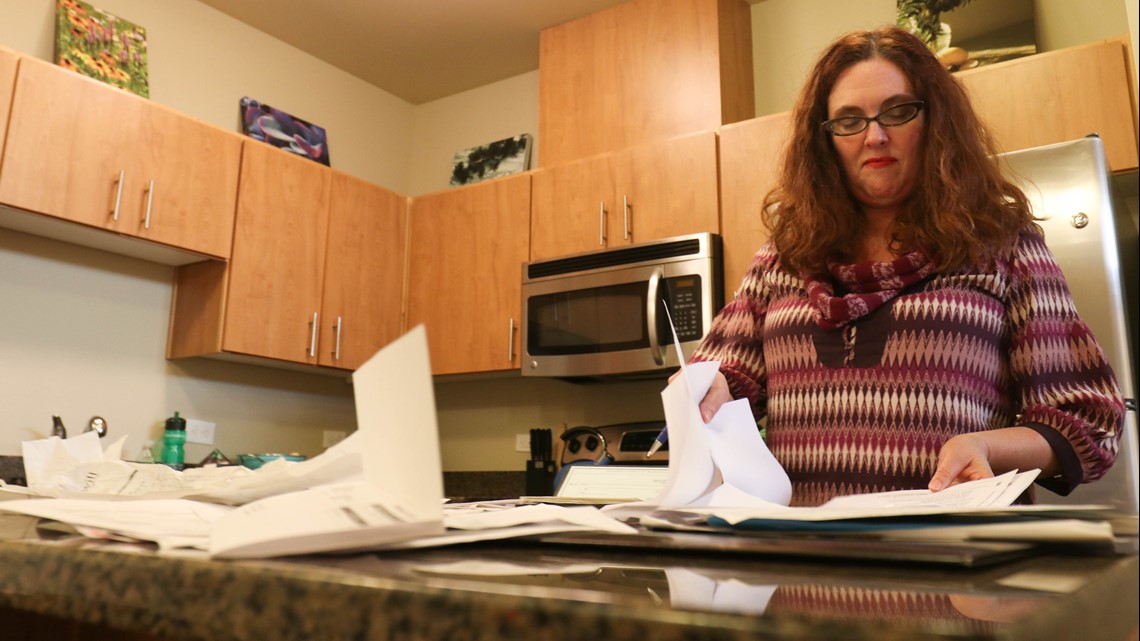

Erin Willison had laid out piles and piles of unpaid bills and credit card statements across the kitchen counter in their new Issaquah apartment — the 10th place the family has lived in about seven months.

"Sometimes I just put it all in this little drawer here and try to pretend like it's not really happening," she said.

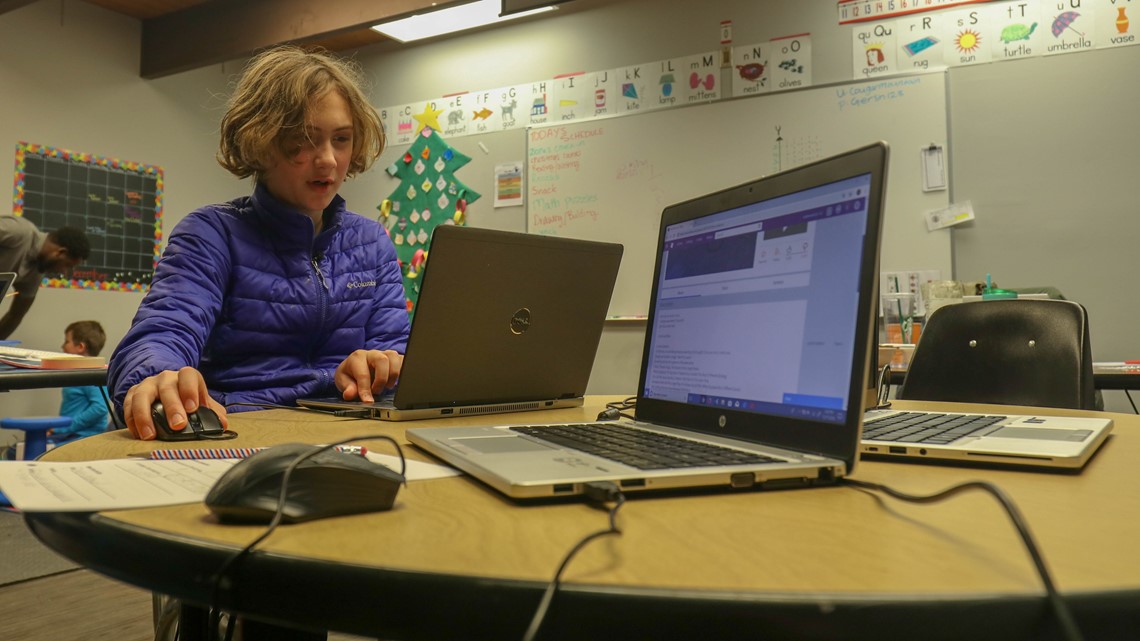

Despite the family’s financial stress, Erin and her husband, Scott, smiled as River cheerfully shared details about his day at Gersh Academy, the private school he’s attended since July. The Issaquah school, which caters to students on the autism spectrum, is located 93 miles from the family’s Bellingham home.

This school year is the first time the fifth grade student, who has autism, anxiety and obsessive compulsive disorder, has been able and willing to go to school full time since first grade.

"It's worth every bit of sacrifice — financially, emotionally," Erin said. "We believe in him."

River and other children with disabilities are guaranteed the right to a "free appropriate public education" under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. But for the Willison family, and many other families who have children with special needs, accessing that individualized instruction is a costly fight.

“I think the vast majority of people who make decisions about these kids lives have no idea how difficult life is for these parents,” said Charlotte Cassady, a Seattle-based special education attorney who helps parents, like the Willisons, secure educational services for their children.

Erin and Scott say they are more than $100,000 in debt because they’ve gone to great lengths to get their child an appropriate education. River’s experience in the Bellingham School District psychologically traumatized him and left him unable to set foot inside a school. He was hospitalized three times, including two, six-week stints at a behavioral health outpatient treatment center in Florida.

The situation led to two legal battles with the district. It also forced the Willisons to uproot their lives, separate their family and take months off of work in order to support River, who medical providers warned needed different resources and educational tools than the district had in place.

“River was, and remains emotionally scarred from his experience at Geneva (Elementary School),” Catherine Fisher, a medical provider, wrote to Bellingham School District staff in August 2016. “It is not an overstatement to say his experience amounted to torture.”

A KING 5 investigation found this pattern: As families push to get their children with disabilities the resources they need to succeed in school, some school districts dig in their heels. They refuse to deliver on promised services without a legal fight. It forces parents to fork out thousands of dollars to cover attorneys fees and pay out of pocket for things like private therapies and schools. The battles often leave families exhausted, stressed out and in financial ruin.

"Any financial impact on a special needs family is at least twice as devastating as a traditional family," said Sheldon Sweeney, a Bellevue financial adviser who works with parents who have children with disabilities.

The Washington state legislature has historically underfunded special education by millions of dollars, and experts say that’s one reason why school districts push back on providing appropriate special education services to the children who need them.

But federal law is clear: No matter how rich or poor a public school is, the district must still offer and fulfill individualized education programs (IEPs) for every child who is eligible for one. The legally binding documents are intended to help kids with disabilities reach general education goals.

Early School Failures Spark School Refusal

Medical providers who evaluated River wrote in records, reviewed by KING 5, that the Bellingham School District failed to consistently implement his IEP or follow his behavior intervention plan. The missteps began, they said, when River was enrolled at Geneva Elementary School during first grade and the start of second grade.

“Unfortunately, there was not a curriculum in place to support his strengths,” wrote Shelly Brask, an occupational therapist, in an August 2015 letter to the school district. “He was often ‘punished’ for the skills that set him apart (information seeking, high verbal skills, and anxious behaviors that interfere with classroom participation).”

River is a cautious and skeptical child, who is slow to build trust with adults and peers. When he feels rejected, shamed or misunderstood by the people around him, his anxiety spikes, according to his parents. He’s fascinated by elevators and toilets, and when he’s stressed or anxious, he self-soothes with OCD rituals related to those things.

Both River’s parents and his medical providers report those behaviors can appear disrespectful, oppositional and disruptive when his stress level is high. They say his educators didn’t use the correct tactics to manage his anxiety. Instead, they misinterpreted the child’s outbursts and rituals as willful.

“He has been shamed in front of the class for behaviors he has difficulty controlling,” Fisher, River’s psychiatric nurse, wrote in March 2015. “The teachers’ response often worsens the anxiety and thus exacerbates the behavior of the child.”

A review of River’s discipline reports reveal that school staff responded to his outbursts with isolation and restraint. During a six-day period in second grade, River was either isolated or restrained seven times. In one incident, school officials documented that the intervention lasted three-and-a-half hours.

“I felt like I was in a dungeon," River said, when asked about the isolation. ”Like I felt like I was never going to be able to do any fun things again or anything.”

Under state law, school districts are allowed to isolate or restrain students only when there is a threat of imminent harm. While the district cited safety concerns as a reason for using the tactic, River’s medical providers determined it wasn’t the right option to address the child’s behavior, according to a review of his medical records.

“It was traumatic for him, and it shaped his future,” Erin said. “He stopped trusting. He stopped believing. He stopped thinking of himself as a capable learner. He stopped thinking of himself as a friend. He started thinking of school as an unsafe, dangerous place, and he just said ‘I’m just a scared kid and nobody knows how to help me.’”

His response to the intervention was severe. His parents said they were forced to pull him out of Geneva Elementary School after the first six weeks of second grade because he refused to walk through the front door.

“He gave up, and when he gave up, he gave up hard,” Erin said.

A Psychotic Break

In lieu of attending the elementary school, the Bellingham School District placed River in a program with home-based instruction, where he didn’t have access to the special education services experts say he needed to effectively manage his anxiety and learn.

Even though he no longer attended the elementary school that caused his trauma, his school-related anxiety spilled into his life at home.

“He had rendered himself invisible,” his mom said. “To see him not sleeping at home, not eating and to see this sort of glazed over child that’s, sort of, almost like a zombie….I mean, we were really, really concerned.”

Erin said her son had a psychotic break and threatened to kill himself in August 2016 — on the first day of third grade.

She said River overheard her planning his upcoming curriculum with a school official on the phone. He ripped the doors off the hinges, punched holes in the walls, and then he ran outside and threatened to jump in front of a car.

‘He said, ‘I’d rather be dead than go to school,” Erin recalled.

River climbed on top of the neighbors’ shed, Erin said, and threatened to jump off. It led to the first of three hospitalizations. It eventually required the family to relocate to Florida on two separate occasions so River could attend a behavioral health program that would help manage his anxiety and OCD.

“(The Bellingham School District) should not have let the situation get to that extreme… without grabbing the bull by the horns and offering an appropriate program to him,” said Cassady, the attorney who has represented the family for about four years.

During those Florida stays, Erin took time off of work to support her son. She said she went months without bringing in an income.

River’s parents said the Florida program helped to ease their son’s school-related trauma, and he succeeded in the program.

But back in Bellingham, the educational placements the school district continued to offer River didn’t work, according to the family and a review of River’s school and medical records. He continued to have challenging days at school, and for long periods of time, he refused to go.

Experts said River needed access to a one-one-one aide specifically trained to work with children with autism, and he’d benefit from a different approach than the school district was providing.

“If River is responding in the way you described, then I have to ask how the teachers are presenting their demands,” Dr. Josh Nadeau, the Florida doctor who oversaw River’s care, wrote to River’s district-appointed psychologist in a January 2018 email.

“There’s no way to say this without offending your teachers,” he added. “But if I want River to be successful, then we’ve shown that’s pretty easy to do.”

'He Thinks Of Himself As Homeless'

Since River wasn’t responding to the Bellingham School District’s solutions, he and his mom relocated to King County in June 2018 so he could attend Gersh Academy.

They had requested that the Bellingham School District place him there and pay for the tuition, which amounts to $137,000 a year. It was the only school, the family concluded, that had the resources to meet their son’s unique needs. But for months, the school district refused.

In River's school records, district staff wrote that they rejected the parents' request because "students who must be educated outside their neighborhood must be educated as close as possible to home."

As Cassady, their attorney, pressured the school district to pick up the tab, Erin was busy searching for the family’s next place to stay while River attended school.

She said she drained their savings to purchase a trailer so the family could be near Gersh Academy. They lived in that trailer through mid-fall. Later, Erin and River moved into friends’ basements for weeks at a time — until finally, they started renting their own apartment in Issaquah in January.

“He thinks of himself as homeless,” Erin said.

Last month, the family settled their second legal case against the Bellingham School District. The district agreed to reimburse the Willisons $45,000 to cover a portion of their legal fees. They also agreed to pay River’s tuition at Gersh Academy until he graduates from high school — as long as the family maintains a residence in Bellingham.

River’s dad, who owns a Bellingham business, commutes back and forth to visit River and his wife in King County each week. But he still lives in the Bellingham home.

The district declined to pay for the family’s living and transportation expenses.

"It's the emotional part that's the hardest for me and for our family,” Erin said. “We have been driven apart. We've been displaced from our home. From my marriage…We're not able to be a family we need to be right now, and it's stressful."

Dana Smith, a spokeswoman for the Bellingham School District, declined KING 5’s request for an interview to discuss River’s case, and she declined to respond to the family’s claims. She cited the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act, which prevents school districts from sharing personally identifiable information regarding students.

She said the district works with families of students receiving special education services to provide a free appropriate public education in their neighborhood schools or as close as possible to the student’s home.

Under the terms of the settlement agreement, the Bellingham School District accepted no fault.

“I just wonder how many other people are out there that can’t take time off of work — that don’t have the luxury of a two-parent family,” Erin said. “(How many people are out there who) aren’t willing to sleep on a couch or live in a trailer or hire an attorney? I mean, those are all scary, risky, things that nobody wants to have to do.”

Other Families Forced To Make Financial Sacrifices Subtitle here

There are plenty of other Washington families who make significant sacrifices as they fight with school districts to give their children their basic educational rights.

Lindsay Legg, for example, was forced to drain her savings and eventually sell her dream home because her non-verbal son Noah, a 6-year-old with autism, didn’t have a place to go to school.

Officials at the small Snohomish County school district in Index — the town where the family lived — told Legg that they didn’t have the resources to support Noah’s unique needs.

As a result, the single mother had to get a second job to afford to send her son to a private therapy program in Kirkland, which cost her hundreds of dollars a month. She and Noah spent three hours a day traveling to and from the therapy center, which was 42 miles away from their home.

“We have enough battles that we fight all the time above and beyond what a neuro-typical kiddo might face," Legg said. "Getting a basic education should not be one of them.”

Kris Hafey, an Olympia mother, said she’s still dealing with the financial loss her family suffered after Braedon, her 7-year-old son with autism, was isolated and restrained dozens of times in the Tumwater School District.

She said she and her husband both had to leave the workforce at times in order to stay home with their son, who was repeatedly sent home for behaviors directly related to his disability.

As a result, she said, they had to take out a second mortgage on their house, and they raised money on GoFundMe to pay off the loan.

“It’s horrible to have to ask people to pay for your housing,” Hafey said. ““Those are things we should be able to take care of ourselves.”

She said they also took out a loan to pay their bills, and they sold odds and ends— a bike and tools — online in order to make ends meet.

While the Legg, Hafey and Willison families all hired attorneys and reached settlement agreements with their local school districts, experts say these families are the exception.

Many families can’t afford to hire an attorney to begin the fight.

”It’s often horrible what’s happen to those children,” said Cassady, the special education attorney. “Frankly, the districts knew they couldn’t enforce their rights because they knew they couldn't afford to enforce their rights.”

Resources And Support

If Your Child Has A Learning Disability

Know your rights. The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction offers guidance for families, which includes a handbook with information about you and your child's rights under state and federal law.

If you have questions about the special education process or difficulties communicating with your school district and need additional help, OSPI has special education parent liaisons available to assist you.

The state also has education ombuds who work with families to answer questions and help resolve concerns. Contact their office online or by phone at 866-297-2597.

About This Series

This story is the tenth part of "Back Of The Class," a multi-part investigation into the state of special education in Washington. The series exposes the reasons why Washington lags behind much of the country in serving one of our most vulnerable populations: students with learning disabilities.

Part 2: Washington kids with disabilities often denied right to learn in general education classrooms

Contact The Reporters

Susannah Frame is the Chief Investigative Reporter at KING 5. Her stories have exposed many wrongs, leading to changes in public policy, congressional investigations, federal indictments and new state laws. Follow her on Twitter @SFrameK5 and like her on Facebook to keep up with her reporting. For story tips or questions, e-mail her at sframe@king5.com.

Taylor Mirfendereski is a multimedia journalist, who focuses on in-depth reports and investigations for KING 5's digital platforms. Follow her on Twitter @TaylorMirf and like her on Facebook to keep up with her reporting. For story tips or questions, e-mail her at tmirfendereski@king5.com.