KENT, Wash. — Ellen “Ellie” Carter is still proud to show off her miniature desk and the new school supplies her parents bought her to start off the school year.

She also bragged about the colorful art project she made 10 weeks ago during the first week of second grade, when she livestreamed into her general education classroom from her Kent home.

That was the last time the 8-year-old special education student, who has well-documented medical issues that preclude her from safely attending class in person, received her full education. In September, the Kent School District abruptly pulled the plug on her virtual access to her Emerald Park Elementary school classroom and left Ellie with little instruction for the last two and a half months.

“I’ve missed a lot. A lot. I don’t really do school,” said Ellie, who now receives just an hour and a half of educational instruction each week. “Sometimes I make pretend math problems for myself.”

As a student with diagnosed medical conditions and learning disabilities, Ellie has a right under state law and the federal Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA) to receive specialized educational services and a free appropriate public education. She’s one of about 143,000 students eligible for special education services in Washington state. But for more than 10 weeks, the Kent School District has not fulfilled her individualized education plan (IEP), the legally binding document that spells out what extra or different services Ellie needs to succeed in school.

“It made me kind of sad,” said Ellie, who doesn’t fully understand why she was pulled away from her second grade class. “I really hope that just like everyone who needs to go to school can go to school, and I’ll get vaccinated soon.”

Ellie, who was expected to attend virtually this school year as an accommodation for her special needs, has fallen victim to an ongoing union dispute between the Kent School District and the Kent Education Association over the working conditions of teachers. At issue is whether the school district has an obligation to give Ellie’s general education teacher more resources and compensation for allowing her to livestream into the classroom while he delivers in-person instruction to other students at the same time.

“In all the years I’ve been doing this, this is the first time I’ve ever had the teachers union interfere with the implementation of an IEP,” said Jeannette Cohen, a special education attorney representing the Carter family. “I don’t believe there’s any legal authority for a child’s program to be held hostage by a teacher’s union.”

‘You have a very vulnerable population of students who aren’t being served’

School districts in the state of Washington have a long history of denying equal education access to students with special needs, as a multi-part KING 5 investigation uncovered in 2018. But there are early signs, according to the U.S. Department of Education, that significant educational disruptions caused by COVID-19 are exacerbating long standing academic disparities for students with disabilities nationwide.

While the circumstances of Ellie’s inability to access her education are seemingly unique, she joins an untold number of other special education students across the state who have suffered significant setbacks as a result of the pandemic. Interviews with the parents of 10 Washington students with disabilities and a review of dozens of special education community complaint decisions issued by the state Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) during the pandemic reveal that across the state, many children with disabilities have not received essential services, therapies and other accommodations that are necessary to access their education and achieve IEP goals.

“It's a serious civil rights issue because you have a very vulnerable population of students who aren't being served and who are being left behind,” said Kathy George, a Seattle-based special education attorney and advocate for students with disabilities.

It’s a reality that has led some parents to either pull their children with disabilities out of the Washington state public school system or supplement their public education with costly private therapies and personal aides.

Woodinville residents Carrie and Matt Mizenko said they felt they had no other choice but to pull their 8-year-old son, Bjorn, out of the Northshore School District last school year because the district was fully remote. Bjorn has multiple disabilities, including autism, epilepsy, speech apraxia and vision difficulties. The Mizenkos said school officials did not offer the student the ability to access his full education in person — even though it was clear he was unable to successfully access his specialized instruction via a computer.

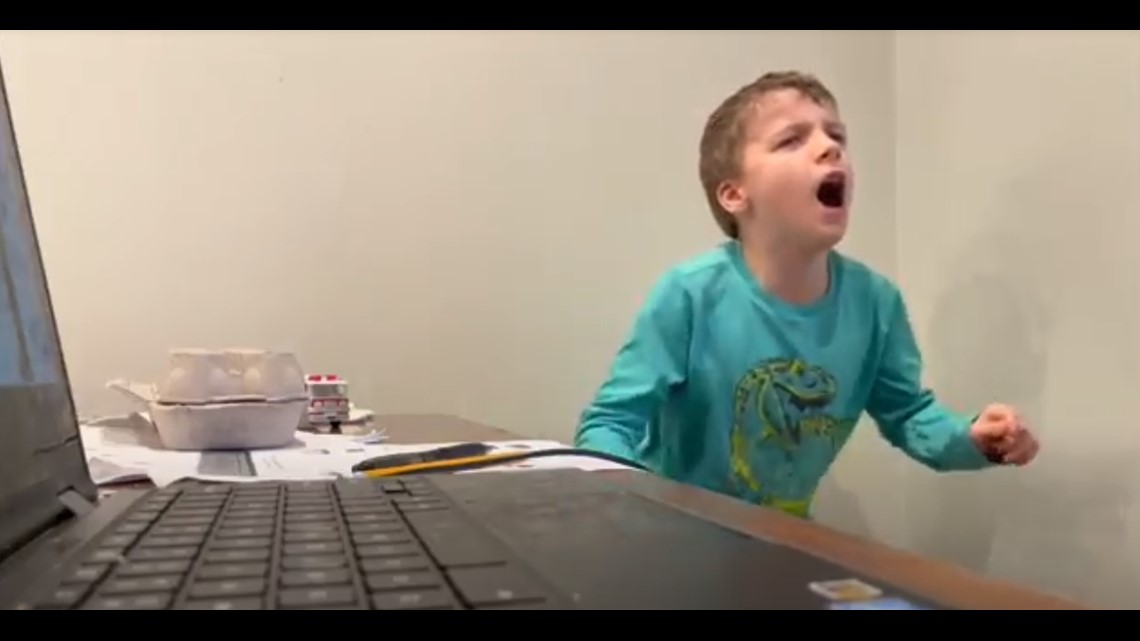

The parents, who have since enrolled Bjorn in a private school that specializes in serving students across the autism spectrum, documented in videos how the child floundered and regressed as a result of remote learning. Bjorn responded to virtual instruction with verbal outbursts and self-harming behaviors, like slamming his head against the wall, screaming and banging his hands against his laptop keyboard.

“We saw regression on every front. His demeanor and attitude went largely downhill,” his father, Matt Mizenko, said. “We started to notice some decrease in the amount of language he was using and the clarity of his diction and speech.”

While remote learning has been disastrous and ineffective for some students with disabilities during the pandemic, there are plenty of children like Ellie who, because of certain disabilities or health conditions, continue to require access to a virtual education to achieve their IEP goals.

“We’re hearing firsthand from some parents who want their children to continue with remote instruction,” said Glenna Gallo, special education director for OSPI. “The IEP team needs to meet and consider the request and make a decision based on the student's unique needs.”

Washington special education attorneys who represent families of students with special needs say it’s increasingly been a struggle for their clients to access an appropriate education online this school year. They say it's because school districts across the state were required to prioritize making in-person learning available to all students and some districts opted not to offer a virtual option.

“It's a major problem. I've heard of many parents being frustrated because their children really are not able to safely access school now that school is back in person,” George, the Seattle-based special education attorney, said. “Unfortunately, school districts are not recognizing that children have a right to be educated in the home, based on their individual health and safety needs.”

Some districts have decided to offer a hybrid model of remote and in-person instruction, while others opted to contract with one of the hundreds of virtual programs or academies in Washington state. It’s not yet clear how many of the state’s 295 school districts decided not to provide a remote learning experience during the 2021-2022 school year. OSPI, the state education agency, is expected to release the latest school enrollment data in January on the number of students who are attending class remotely this school year.

‘She’s at high risk to have the worst response possible’

The Kent school district returned to full-time in-person learning during the 2021-2022 school year and chose not to offer any virtual option to families.

But it was not possible for Ellie to physically go back to class.

Her doctor decided in August, amid increasing cases of COVID-19, that it was too dangerous because of her chronic health concerns, including lung damage from premature birth. He advised Ellie should attend school remotely until she can “either be vaccinated or COVID cases decrease,” according to a review of the letter he wrote and provided to Kent school officials.

“If she were to catch something, she's at high risk to have the worst response possible,” Ellie’s father, Andy Carter, said. “(The doctor) said, ‘Keep her home. Find another way.’ Because it wasn’t safe.”

Even though Ellie couldn’t attend in person, her most recent IEP stated that it was imperative she spend most of her day — nearly 75% — in a general education setting to give her the best shot at tackling academic goals and social skills, which includes interaction with peers.

State law guarantees that she and the nearly 150,000 special education students in Washington have a right to go to school in the “least restrictive environment.” It means they should get the opportunity — to the maximum extent appropriate — to learn in a general education setting around children who are not disabled, even if they can’t keep up academically or if schools have to modify the way the children learn with extra support.

In August, before the start of the school year, the Kent School District and Ellie’s parents worked out a solution to ensure Ellie would have proper access to her general education class. She would livestream into the classroom, and her one-on-one paraeducator would monitor the camera.

“It was kind of different for me, but I met new friends,” Ellie said.

By her parents' account, the first few days of class in August were a big success. In Ellie’s classroom, the camera sat at the child’s actual desk so she could say hello to her neighboring classmates and even raise her hand.

“She would smile and wave. They’d talk back and forth. It was great.” Carter, her father, said. “To see my daughter so happy, to see her get some additional interaction with her peers, it made me feel good. It made me feel like this process is going to work.”

‘I was in shock’

Five days into the school year, on Sept. 1, the plan fell apart. The Kent School District informed the Carter family that Ellie would no longer be allowed to livestream into the classroom.

“I was upset. I was in shock. I don’t understand how you can just cut someone off at the knees with no conversation,” Carter, Ellie’s dad, said.

Ellie’s parents hired an attorney and filed an OSPI special education complaint, as weeks without answers or access to Ellie’s classroom went on.

In a written response to the family’s complaint, an attorney for the Kent School District told the state that school officials followed “appropriate procedures in developing and implementing” Ellie’s special education plan. Though, the district acknowledged “confusion” over Ellie’s ability to livestream “has had a negative impact on her receipt of services.”

The district representative went on to explain that Ellie’s livestreaming “had to be stopped as a result of concerns regarding the privacy rights of other students and teachers in the classroom and due to objections from the local education association.”

Tim Martin, president of the Kent Education Association (KEA), said the union objected to Ellie livestreaming arrangement because the school district refused to provide her second grade teacher with additional time, resources, training and compensation.

Martin said the union believes those extra resources are essential for educators to simultaneously deliver a high quality education to students learning virtually and the other kids who physically attend class in the district.

“We’ve tried to bargain this repeatedly,” said Martin, who represents nearly 2,000 educators in the district. “It’s like pounding my head against the wall to get our district to understand what teachers do and the differences between online instruction and in-person instruction. Our district thinks putting a camera in the back of the classroom is just like teaching in person, and it isn’t.”

“They would rather postpone access for students than to provide the resources and support that are necessary for everyone to be successful,” Martin added.

Jeannette Cohen, the attorney representing the Carter family, argues that there's a significant difference between educating students remotely and allowing a student, like Ellie, to livestream into the classroom.

"All we're asking for is when (the teacher) does his lesson plans and he's making copies for all the kids, let's take one of those copies off the pile and put it aside and let the paraeducator put together a folder for Ellie's work," she said.

She said it not acceptable for Ellie’s special education services to be influenced by a union dispute. In 2018, OSPI issued a bulletin to school districts that reinforced that the requirements of special education laws “cannot be bargained or contracted away.”

“The school district as a whole needs to get itself together and come up with a strategy on how to resolve this,” Cohen said.

Melissa Laramie, a spokesperson for the Kent School District, declined an interview request and did not respond to detailed questions about Ellie’s situation or the district’s dispute with the union.

In a written statement, she explained that the district is aware of Ellie’s family’s concerns about the child's education, and she said that district officials are “continuing to work with the family” to support Ellie's needs. She added that the Kent School District abides by the bargaining process.

“Wages, hours, and working conditions are mandatory subjects of bargaining. As a district, we honor and respect the bargaining process, and all bargaining must happen at the bargaining table,” Laramie wrote in a statement. “For months we have been working collaboratively with our partners in KEA, and we will continue working with our labor partners until a resolution is reached.”

The Kent School District recently agreed in a newly proposed IEP that Ellie should continue to livestream into her special education classroom, according to a review of the draft document sent to the family on Monday.

But Andy Carter said he worries the ongoing union dispute could still keep his daughter waiting without full access to school.

“I can tell it’s hurting her,” he said. “Going on three months without education, without having access to your peers – how do you make that up?”