‘He’s just so sick:’ Landfill employees concerned about arsenic exposure amid King County violations

Cedar Hills Regional Landfill is home to a years-long arsenic problem that has both plagued and puzzled the county.

Even the simplest of tasks are harder for Jon DeMello than for most people.

Whether it’s a trip to the grocery store, a trip to the mailbox or just a walk up the stairs, he said he becomes so winded that he has to stop everything to catch his breath.

“It hasn’t been easy, that’s for sure,” he said.

DeMello, 75, has been in and out of Washington state hospitals and medical clinics for years, searching for answers about why he developed the lesions on his lungs that doctors said are contributing to his respiratory problems. It’s the latest medical condition of many for the North Bend resident, who previously had kidney cancer and open heart surgery.

Now, doctors who specialize in occupational and environmental hazards are looking into whether arsenic exposure at the King County landfill where DeMello works has affected his health.

“He’s just so sick, and he’s not getting any better,” said his wife, Debbie DeMello.

For more than 30 years, DeMello has worked for King County’s Cedar Hills Regional Landfill as a truck driver. The 920-acre facility in Maple Valley is where all but two cities in King County dump their trash. But it’s also home to a years-long arsenic problem that has both plagued and puzzled the county – drawing attention from environmental regulators and concerns from employees.

A KING 5 investigation found that for a decade, the King County Solid Waste Division repeatedly discovered high levels of arsenic at the Cedar Hills landfill – violating state and local rules that exist to protect the environment and public health. Multiple landfill employees accused their bosses of failing to adequately inform employees or protect them from the highly toxic chemical, including DeMello and at least two King County engineers.

“We’ve always been told that, ‘It’s not a hazardous environment. You’ve got nothing to worry about. You work in a safe environment,'” DeMello said. "We never were told that arsenic in high levels was at the landfill."

Arsenic is a naturally occurring chemical that is found in food, water, soil and the air. It can also be released into the environment by certain agricultural and industrial processes.

The inorganic form of arsenic is a highly toxic carcinogen that can cause negative health impacts from long-term exposure to high levels. According to the World Health Organization, adverse health effects can include heart disease, lung disease and cancer, but it can be difficult to distinguish the medical conditions caused by arsenic from conditions induced by other factors.

The King County Public Health Department and the Solid Waste Division said the arsenic at Cedar Hills doesn't pose a health risk.

But some workers are skeptical of that assessment and are calling for more thorough evaluations.

The arsenic discovery

Exactly how high levels of arsenic made it to the Cedar Hills landfill is controversial, according to a KING 5 review of court documents and public records from local, state and federal agencies.

Records show elevated levels of arsenic were discovered as part of King County’s process of managing its landfill gas – a natural byproduct of decomposing trash. Landfill gas contains about 50 percent methane, 50 percent carbon dioxide and a small percentage of toxic chemicals, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

To prevent hazardous chemicals from escaping into the atmosphere, landfills typically choose to burn the gas or convert it to be used as a renewable energy resource.

Since 2009, Cedar Hills' landfill gas has been converted into renewable energy. A private company called Bio Energy Washington (BEW) contracts with the county to capture the landfill gas and convert it into natural gas. The operation provides enough gas for about 19,000 homes each year, according to the company.

That process of creating natural gas produces a liquid called “condensate,” which contains much of the arsenic that led to trouble for both King County and the energy company that operates at the landfill.

BEW and King County are currently in a stand off – a legal battle – about who is responsible for causing and addressing the elevated arsenic. The county alleges that BEW’s industrial processes led to the elevated levels. BEW, which has shut down operations amid the lawsuit, claims King County's landfill gas already contained too much arsenic when the company received it.

“I don’t believe we’ve done anything wrong. We’ve got nothing to hide,” said Kevin Singer, the BEW plant manager who oversees the company’s operations at Cedar Hills. “We don’t add arsenic into the process so all the arsenic…comes from the landfill gas that was delivered to us from the county.”

King County's violations

King County got in trouble with regulators because for a decade, BEW dumped its arsenic-laden condensate into two landfill lagoons.

The wastewater in the lagoons is discharged into King County’s wastewater treatment plant in Renton – the same place where sewage is treated before it flows into the Puget Sound.

To protect toxic chemicals from entering the waterways, oversight officials from King County’s Industrial Waste Program (KCIW) set limits on how much arsenic is allowed to be in water that goes to the plant for treatment.

The agency determined that for years, King County’s Solid Waste Division exceeded the amount of arsenic it was allowed to dump from the Cedar Hills landfill, according to KCIW enforcement records reviewed by KING 5.

In 2018, KCIW fined Cedar Hills more than $90,000 for arsenic exceedances that occurred over a five-year period. Oversight officials found the Solid Waste Division was in “significant non-compliance” of its wastewater discharge permit for discharging more arsenic than allowed on 56 occasions between October 2013 and March 2018.

Regulators issued a compliance order to correct the violations. They also ordered the King County Solid Waste Division to conduct additional and more frequent arsenic testing, noting the landfill had "chronic violations” and failed to "accurately report" its noncompliance.

Since then, the Solid Waste Division has remained in “significant non-compliance” of its permit, and it has continued to receive annual violations.

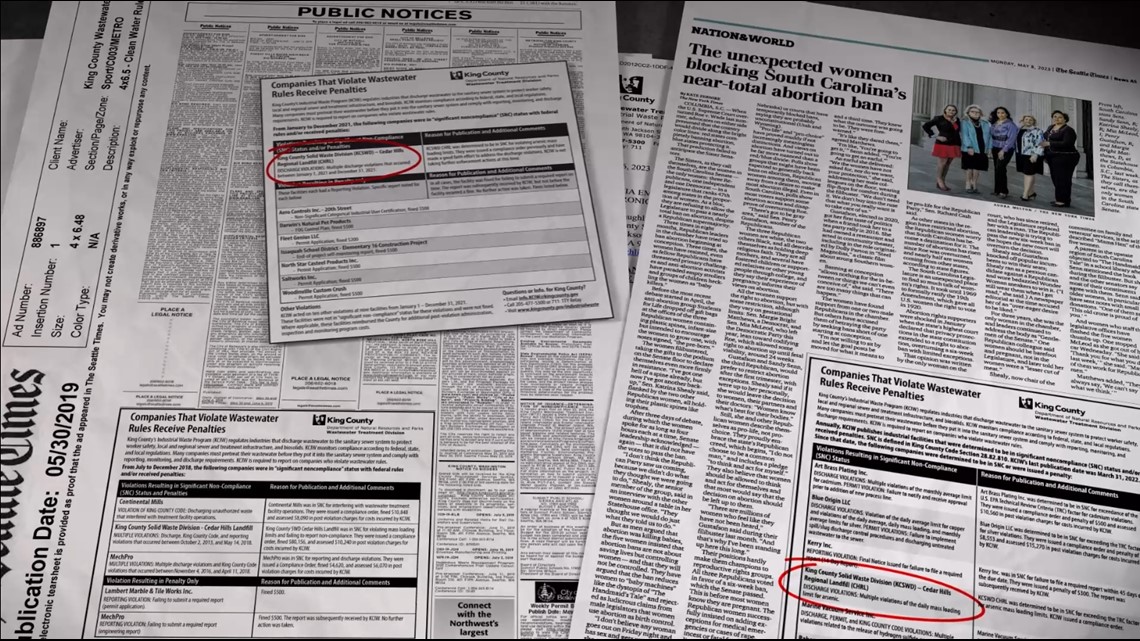

As a consequence, KCIW publicizes the landfill's arsenic violations annually in ads that appear in the Seattle Times – a mandate for companies that violate the Clean Water Act. The most recent ad, which published in May, again called out Cedar Hills for discharging too much arsenic.

Alison Hawkes, a spokesperson for the King County Wastewater Treatment Division, said the landfill's arsenic discharges have "not yet affected" the operations or environmental permits of the Renton-based treatment plant that received the landfill's wastewater.

But, she added, "such noncompliance is a serious matter and must be corrected."

Pat McLaughlin, director of the King County Solid Waste Division, said the county has worked “vigorously” with regulators and industry experts to deal with the problem, and it is currently developing solutions to remove the arsenic.

“It’s easy for arsenic to show up in the landfill. It’s hard to get it back out,” he said.

Hawkes said the Solid Waste Division has “continued to make good faith progress” toward a solution to address the arsenic exceedances, and must develop a workable plan by July 2024.

In addition to the violations from county regulators, the Washington State Department of Ecology and the Washington State Department of Labor and Industries (L&I) also cited the county for violations related to arsenic at Cedar Hills, according to a review of records from those agencies.

Employee Complaints

Colleen Christensen, a veteran engineer for the Solid Waste Division, is one of at least three King County workers who formally voiced concerns about the Solid Waste Division's response to the arsenic problem, according to a review of whistleblower complaints to King County's Office of the Ombuds.

Christensen said the Solid Waste Division tapped her to help investigate the source of the arsenic and work with regulators. But in the process, she said she became concerned that the actions of Cedar Hills bosses put her and her team in danger.

For years, Christensen supervised a crew at Cedar Hills who was responsible for testing the landfill for hazardous chemicals.

Records show, in 2020, a county consultant performed their own testing and found that arsenic levels at the landfill on one day were about 40 times higher than the federal limit for what's considered "hazardous waste," according to a review of the consultant's report.

Christensen said her bosses had the test results, but failed to inform her crew or protect them from the hazardous waste they were regularly sampling.

“I didn’t know it was a hazardous waste. They didn’t know it was a hazardous waste,” she said. “One of my field crew collected a sample … she had to stick her arm down in it, and her arm was red … she said it just felt itchy and horrible.”

A spokesperson for the King County Public Health Department said that despite the county’s permit violations, arsenic levels at the landfill aren’t high enough to pose a health risk.

But after becoming concerned about her own health from arsenic exposure at the landfill, Christensen filed complaints to local, state and federal agencies – calling for more thorough public health evaluations.

“I wanted somebody to do something, and I wanted somebody to do something about it now,” she said.

In April 2021, at least one of her arsenic-related complaints led to action from a state agency. L&I's Division of Occupational Safety and Health fined King County $3,000 and ordered the Cedar Hills landfill to correct workplace safety violations affecting Christensen and her team.

L&I investigators found, in part, that Cedar Hills did not train employees on the hazards of arsenic, did not evaluate employee exposure to airborne inorganic arsenic during a key timeframe, and did not make sure employees who were sampling the contaminated wastewater used personal protective equipment, according to a review of the L&I citation.

The next month, Christensen said her bosses took her off the arsenic project – stripping her of her supervisory responsibilities and removing her from her Cedar Hills office of more than 30 years.

She was reassigned to her Sammamish home office in a different unit, where she said her deep expertise at Cedar Hills isn’t being put to good use.

“What the Solid Waste Division accomplished by moving me out of my office is that I wasn’t there when the regulators came. I wasn’t part of those inspections. I couldn’t show them what they really needed to see,” she said.

The King County Ombuds Office, which responds to complaints of government misconduct, is currently investigating Christensen’s 2021 whistleblower complaint that accuses King County of retaliation.

A spokesperson for the King County Solid Waste Division declined to comment on the matter "to preserve the integrity" of the ombuds' investigatory process.

In 2021, another King County engineer who was one of the county's go to experts on landfill gas and arsenic also filed a whistleblower complaint with the King County ombuds. He accused his employer of creating "substantial and specific danger to the public health and safety," "concealing the truth" and "a lack of transparency."

"Any time there have been concerns raised...that have indicated public risks, we have taken immediate and definitive action to research, to understand and when necessary, take corrective action," McLaughlin said.

"The situations that you're mentioning, we actually did bring in third parties to monitor... and we found no risk to the public health or the environment," he added.

McLaughlin said the Solid Waste Division has been transparent with Cedar Hills employees about arsenic exceedances at the landfill.

"We avail ourselves to our staff on a regular basis to hear about their operational concerns, to address their safety concerns," he said. "They have direct access, not just to their supervisors, but the safety officers."

In response to employee health concerns, Cedar Hills management recently informed landfill workers that the Solid Waste Division hired an industrial hygienist to conduct additional exposure testing for arsenic, according to a review of internal communication sent to employees last month.

A Solid Waste Division spokesperson said the county will share test results with workers when the reports are completed.

For Jon DeMello, transparency is still a sore subject.

"What just drives me crazy is the lack of communication the county had with us," DeMello said.

DeMello and his wife said they just learned of Cedar Hills' years-long arsenic problem in July from a casual mention on a break room flyer.

"Why did they have to wait so long?" his wife, Debbie DeMello said. "I'm really angry."

Watch KING 5's Investigations playlist: