FEDERAL WAY, Wash. — It wasn’t Sam Clayton’s xylophone performance of “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” that brought his parents to tears recently.

It was the roaring applause and standing ovation from Sam’s classmates that followed his performance as the opening act at his high school’s band concert in May.

“I got really really choked up and thought, ‘This is amazing,’” Sam’s mother, Sandy Clayton, said. “This, in such a huge way, was a recognition of Sam.”

Sam, 14, just finished his freshman year at Decatur High School in Federal Way. He was born with Down syndrome.

Until Sam’s performance on the school stage, Sandy and Rob Clayton had never before seen so many other kids recognize their son. The school year prior, at a middle school dance, they watched Sam’s classmates ignore him while he spent 45 minutes in the school gymnasium dancing alone.

"Not one child came and interacted with him. No one came and said, 'Hi Sam,'" Sandy Clayton said. "He experiences every emotion every other kid feels. He knew he was alone."

For this family, the band concert applause was yet another milestone in a year full of academic and social progress for Sam. It symbolized the incredible change that can happen to children with disabilities when school administrators make one simple adjustment to their education: inclusion with students who don’t have disabilities.

“It still boggles my mind that no one came by and said hello to him [at the dance], and now, he just walks down the hall — it’s not even a special occasion— and the kids are saying hi to him,” Sandy Clayton said.

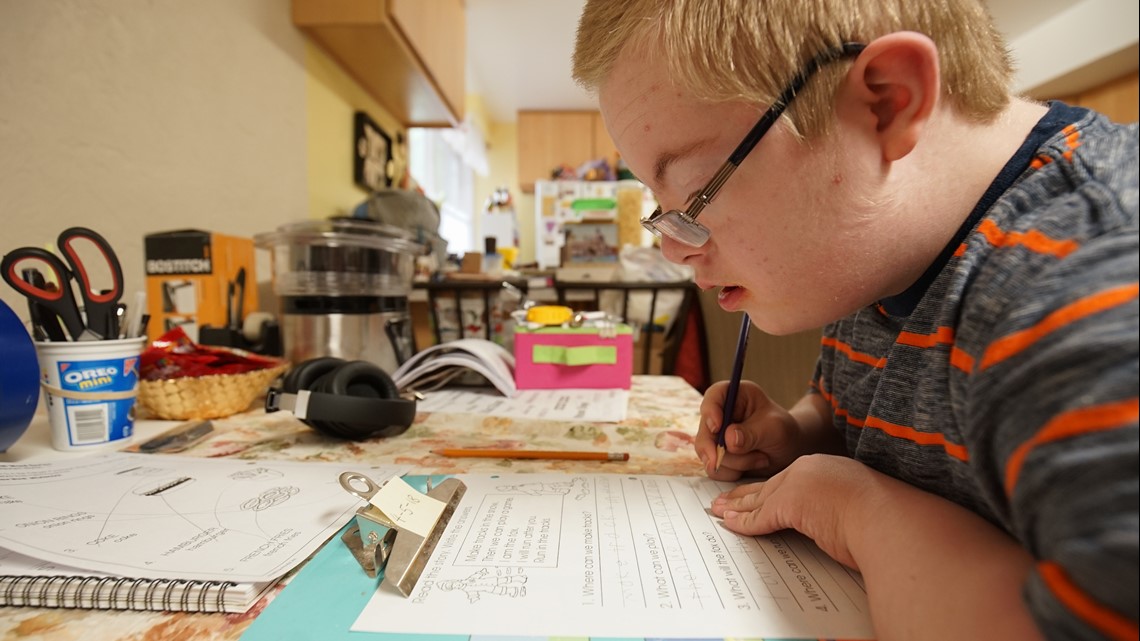

This school year, Sam’s freshman year of high school, was the first time in three years that Federal Way school administrators allowed him inside general education classrooms, learning alongside non-disabled peers for nearly 40 percent of the day. At Taf @ Saghalie Middle School, Sam spent every day in a segregated classroom with other students with disabilities, including lunch.

“[The inclusion is] changing his life significantly,” his dad, Robert Clayton, said.

Sam, who previously struggled to meet his academic goals, was the subject of the second investigation in KING 5’s “Back of the Class” series in May 2018. The investigation found that Washington schools exclude students with disabilities from general education settings more often than schools in nearly every other state in the country.

That’s not supposed to happen under state and federal law. Public schools in the United States are required to provide specialized educational services to all children with a disability recognized under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

That law guarantees that the more than 150,000 special education students in Washington have the right to go to school in the “least restrictive environment.” It means they should get the opportunity — to the maximum extent appropriate — to learn in a general education setting around children who are not disabled, even if they can’t keep up academically or if schools have to provide extra support.

"I see all too often that kids are removed from the regular classroom unnecessarily when they are capable of learning with the right support,” said Kathy George, a Seattle-based attorney and a special education expert.

Just over half of Washington's 6 to 21-year-olds with disabilities spend 80 percent or more of their day in general education classes. Only seven states have a lower percentage of special education students in regular classes, according to an analysis of the U.S. Department of Education’s 39th Annual IDEA report to Congress, published in 2017.

Five percent of Washington's students with intellectual disabilities spend the majority of their day in regular classrooms. Only two states in the country — Nevada and Illinois — have worse inclusion rates in that category, according to the same report.

State Legislature Tackled Inclusion

Following KING 5's investigation, inclusion was one of several special education issues Washington lawmakers tackled in the 2019 legislative session. The legislature boosted special ed funding by $155 million over the next two years to implement Senate Bill 5091, which takes effect next month.

The law bumps up Washington's excess cost "multiplier," which is the amount of additional money the state is required to pay school districts to educate students with disabilities.

It provides a monetary incentive to school districts that educate special needs students in classrooms alongside their general education peers for the majority of the school day, and it adds professional development training for educators on inclusive practices.

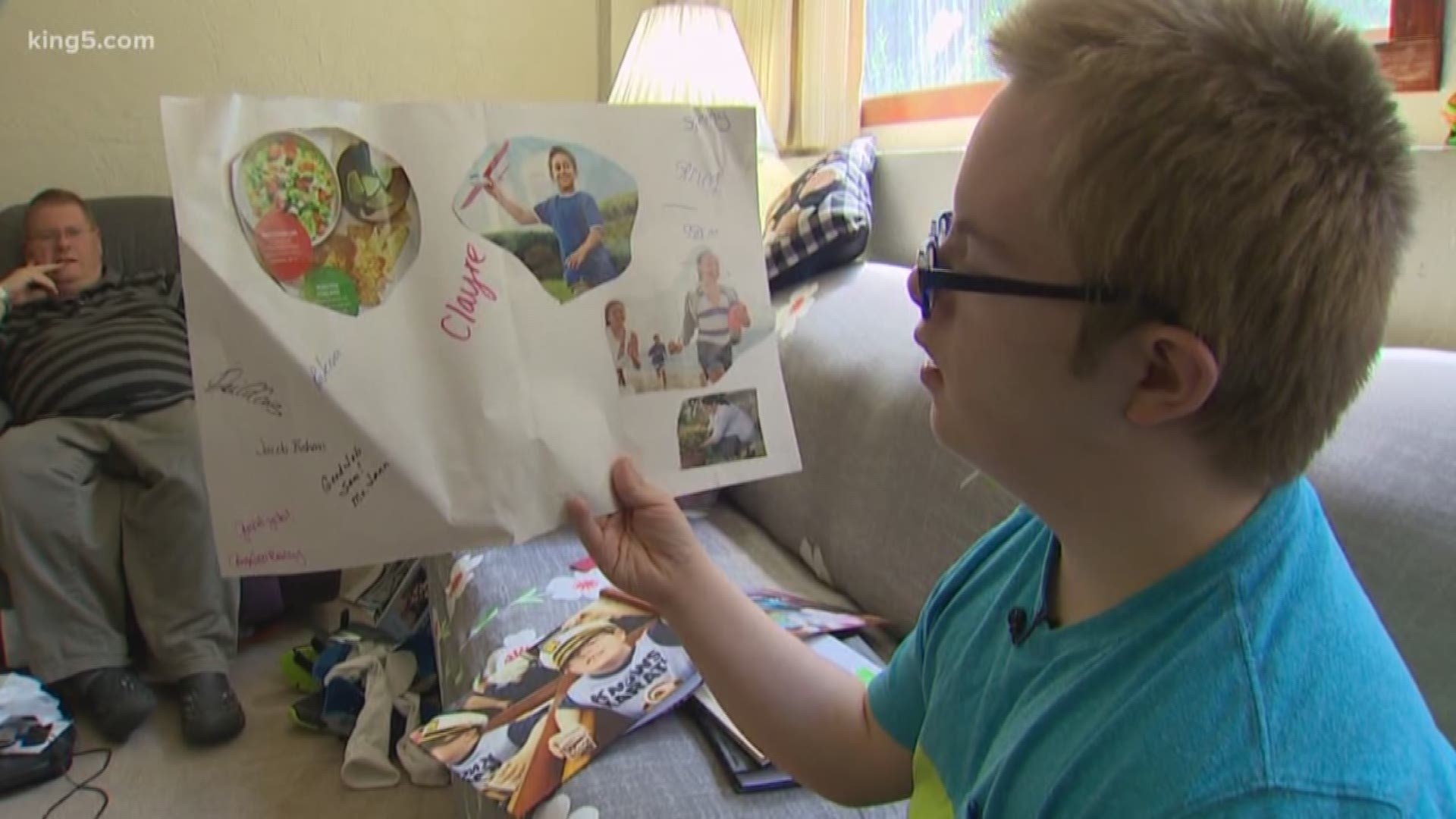

Sam's Progress

In addition to band class, Sam takes pottery and leadership classes alongside typical learners. His parents say he also sits at the same lunch table as students who don’t have disabilities.

“We watched a kid who was generally pretty extroverted in elementary school become more and more withdrawn for three years in middle school, and now we are starting to see the old Sam kind of reemerge and be more confident and silly and social,” Sandy Clayton said. “It’s such a blessing to see that again.”

A review of Sam’s school records shows how inclusion boosted his educational progress. In his year attending class with non-disabled students, Sam made noticeable improvements in math, reading and social skills.

The social improvement is significant to his parents, who notice that Sam has picked up conversational skills and mirrored other behaviors from teens at school.

“He seems to be able to initiate some conversations with us,” Sandy Clayton said. “That’s huge for us because so many times, he couldn’t explain to us what he was thinking or what he was going through at school, but now he seems quite happy and quite content to tell us about his day.”

Robert Clayton said Sam has become more confident, independent, and he’s learned how to advocate for himself in public, too. On a recent trip to McDonald’s and Safeway with his dad, Sam ordered his own drink, greeted a cashier, and helped his dad pick out groceries.

“[He’s] making people aware of what he likes, what he doesn’t like, and also making them feel comfortable and picking up on their feelings as well,” Robert Clayton said.

Sam’s second year at Decatur will see him spending more time each day with general education students, according to his parents.

A Federal Way School District spokeswoman denied KING 5’s request to document Sam’s experience at Decatur. She previously declined interview requests and would not explain why Sam was segregated his entire middle school career.

“I think what we’re seeing now in just the first year of high school shows so much promise, and I think it can only go up from here,” Sandy Clayton said. “I don’t want more for Sam than what other kids are getting. I want equal treatment.”

About This Series

This story is an update to "Back Of The Class" a multi-part Peabody award-winning investigation into the state of special education in Washington. The series exposes the reasons why Washington lags behind much of the country in serving one of our most vulnerable populations: students with learning disabilities.

Part 2: Washington kids with disabilities often denied right to learn in general education classrooms

Contact The Reporters

Susannah Frame is the Chief Investigative Reporter at KING 5. Her stories have exposed many wrongs, leading to changes in public policy, congressional investigations, federal indictments and new state laws. Follow her on Twitter @SFrameK5 and like her on Facebook to keep up with her reporting. For story tips or questions, e-mail her at sframe@king5.com.

Taylor Mirfendereski is an investigative journalist who specializes in in-depth multimedia storytelling on KING 5's digital platforms. Follow her on Twitter @TaylorMirf and like her on Facebook to keep up with her reporting. For story tips or questions, e-mail her at tmirfendereski@king5.com.