Unshackled: A prostitute's journey to freedom

'Everyone thinks only the ones who are pimped are captive'

EDITOR'S NOTE: If you are using the KING 5 app, click this link to view this story with photos and video.

Jennifer Tucker was trapped in the sex industry — beaten, raped and manipulated by customers and pimps for years. But something stronger than chains held her captive.

This is Tucker's journey to freedom.

Coming Out Of Hiding

The text from a pimp wakes up Jennifer Tucker before her alarm.

6:44 a.m.

She doesn't need the reminder. The 39-year-old starred this May day in her pink appointment book three months ago.

Tucker glances in her closet; smiles as she sees the sparkly white gym shoes she bought just for today.

Shoes make the girl.

And this day makes the woman, she thinks.

She wonders: Who will be out there? Will anyone recognize her? She anxiously twirls her damp ponytail into a spiral.

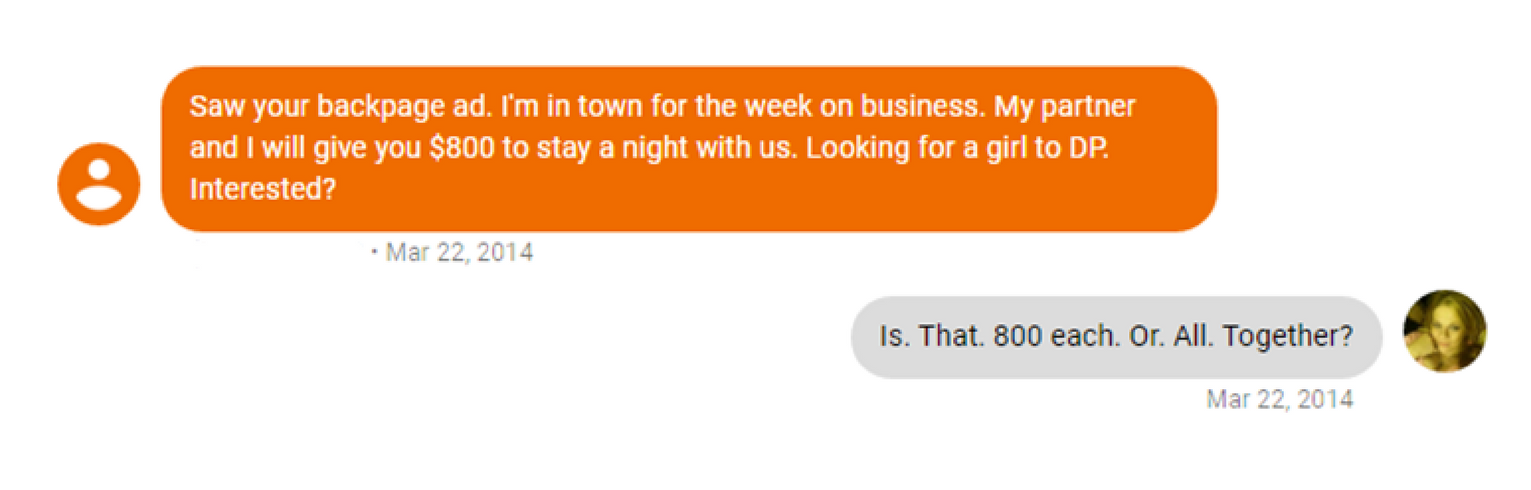

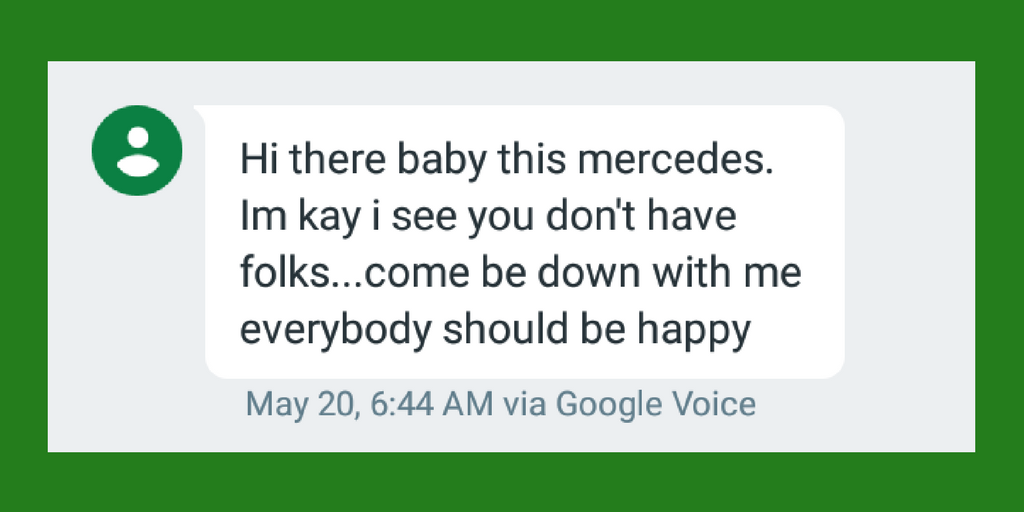

She picks up her phone and reads the flirty text message from the pimp. He addresses her by her working name, Mercedes. They all do.

Even now.

Photo: A screenshot of the text message Tucker received from the pimp on May 20, 2017. "Folks" is a slang term for a pimp.

Photo: A screenshot of the text message Tucker received from the pimp on May 20, 2017. "Folks" is a slang term for a pimp.

"They are relentless," she says.

Standing in a slouchy purple Washington Huskies t-shirt and gray leggings, she digs through the dresser in her Tacoma Hilltop bedroom, next to a nearly-deflated Mother's Day balloon and a pile full of clean clothes crumbled in a cardboard box.

"I've been in hiding, I guess you could say," she shrugs. "Just in my own protective bubble. I don't even go to King County."

"Actually," she says if reminding herself.

"I need a permission slip to go there."

She's feeling sheepish today. So, she whips around and digs through the rumpled clothes in that cardboard box — finally finding the black hoodie, the one with "RECOVERY" on the back.

This way, no one will notice the matching Mercedes symbols branded on each shoulder, the tattoos that once were her calling card in online escort ads.

Looking at her reflection, Tucker dabs neutral powder on her face and applies mascara to her long lashes.

She drowns herself in Victoria Secret body spray, downs a cup of coffee and exhales before she slams the door behind her.

She squints in the sunlight as she heads out.

Grooming Her Future

For thousands of people who make their living in the sex trade, the road to prostitution begins as a choice.

It's not an easy choice for most, but it often spells survival.

"Generally, when older people say that they chose to do it, it wasn't so much a choice," said Debra Boyer, executive director of the Organization For Prostitution Survivorsin Seattle. "It was an alternative to not being able to take care of their kids, to starving."

For Tucker, whose troubled early life sometimes meant trading occasional tricks for cash, the spiral into full-time prostitution started with a failed, abusive marriage.

After she separated from her husband, Rodrigo, he then sent their 2-year-old son and 7-year-old daughter to Brazil to visit his family. That was July 2010.

Rodrigo never sent them back.

She couldn't afford to hire a lawyer to fight for her two youngest kids. She got laid off from her customer service job at the insurance company and after her separation, she left her Kirkland home behind. Her two oldest children were gone, too — living with family members in other states.

Photo: Jennifer Tucker poses with her four children before her separation in 2010. (Provided)

Photo: Jennifer Tucker poses with her four children before her separation in 2010. (Provided)

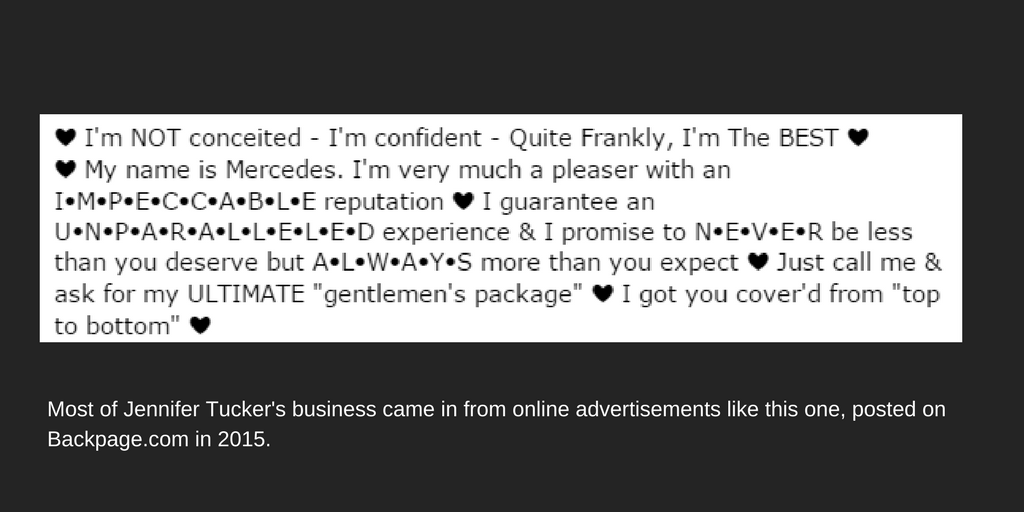

So 32-year-old Tucker reverted back to the one way she knew she could make some quick cash: She posted an ad online for sex. It worked a few times in her early 20s.

A friend in Everett helped her write it.

"Just call me & ask for my ULTIMATE 'gentlemen's package,' the Craigslist ad said. "I got you cover'd from 'top to bottom.'"

It was just sex, she told herself.

After all, her body had never been a sacred place.

'Bedtime Stories'

Tucker wasn't old enough to utter her first word the first time she was touched sexually. She was barely a year old when her then 16-year-old foster brother fondled her genitals in his bedroom while her parents were at work. He did the same thing to her older sister, too.

At 3, Tucker's parents divorced and her foster brother ran away from home. Tucker and her sister moved in with their godfather. They lived with him, his wife and their mom for the next four years.

She remembers her godfather's brown hair and furry sideburns. But it's the smell of machine oil that radiated when he came close to her that still sticks with her. He was a welder who worked on tractors. Every day he wore a soft white t-shirt and blue jeans, and he drank from a keg in the entryway of his Ellensburg home. Sometimes, he'd make Tucker and her sister drink the beer from a jam-sized jar.

Tucker's mother put her godfather in charge of punishing her when she acted out. He'd lock Tucker in his dark, musty basement for hours until he was ready to come downstairs for "bedtime stories," four or five days a week. On those nights, Tucker stared at a photo of Pinocchio and Jiminy Cricket while her godfather stroked her private parts and read from a book of Disney classics.

She squirmed. He demanded she sit still.

"It was almost like I was his wife for the intimate parts, but his wife was his wife for all the rest of the house," she explained.

Most days, Tucker's godfather took her to work. She'd sit on his lap in the hot tractor cab, where he'd put his rough hands down her pants. That smell of oil — with a hint of bag balm. He coated his hands with that stuff every time he touched her.

Often on the drive back home, he'd pull over the big white van with no windows to touch her genitals on the captain seats in the back.

And on Sundays, he would let her go to the public pool. But she didn't get to play with the rest of the kids. She sat on her godfather's knee in the Jacuzzi, where he'd reach under water for the bottom of her suit.

But she loved her godfather. She loved the way he made her feel needed. That's why she didn't tell a soul.

"Although I was a very sad and lonely girl, he was my comfort," she said.

Her sister broke the news of the abuse to their stepmom, Sheri, and father Bill Tucker right after Tucker's 7th birthday when a sexual abuse commercial came on the TV.

In April 1985, Bill Tucker went to the police and attempted to press charges. But a month later, the City of Ellensburg lost the in-depth recorded statements Tucker and her sister provided to police. The elder Tucker decided to drop the case because he didn't want to re-traumatize his daughters, who moved back in with him as soon as he learned of the abuse.

"We were sickened, and I was furious," he said.

Tucker's godfather was never charged with a crime. He died from cancer in 2002.

Photo: A portrait of Jennifer Tucker as a young girl. (Provided)

Photo: A portrait of Jennifer Tucker as a young girl. (Provided)

"The things I went through as a younger child always had an effect on me," Tucker said. "If it hadn't ever happened to me, I am pretty sure I would never have gotten into the lifestyle."

RELATED: Why is Tucker sharing her story?

Some studies estimate as many as 95 percent of sex workers suffered some form of childhood sexual abuse.

"If you are worried about your mother's boyfriend or somebody else climbing into bed with you when you are 4 years old, you're not going to have a normal childhood. You're getting groomed," said Boyer, the prostitution expert.

"A child who has been sexually abused has to adapt to that to survive, which is basically preparing them to prostitute if that situation offers itself," she added.

'I Didn't Have Anything, Y'Know?'

As an adult, that childhood trauma resurfaced for Tucker when her picture-perfect family fell apart in 2010.

By July 2011, Tucker's youngest children were still in Brazil, and she was still selling herself. But she wasn't any good at marketing herself online and had no money to win her kids back. She barely had enough to survive.

"My behavior was erratic and completely different," she said. "I lost my mind."

Then a California man responded to her ad and promised to help her change that.

He introduced himself as "B."

"(It) kind of first started with 'You're so pretty,' and just a simple conversation for a month or two and then (he) asked if I would ever relocate," Tucker said. "I mean, he was cute — somebody that would be there for me. I was really lonely at the time."

"I didn't have anything, y'know?"

B was a flirtatious charmer, who said he wanted to be Jennifer's boyfriend and right-hand man. He told her how much more the girls were making in the "adult entertainment world" in California, and he promised to show her the ropes.

He spouted big promises: She'd make more than enough money to get her kids back and she'd have him right alongside her — a trusty companion to help her through every step.

She could tell by the over-sized chinchilla fur coat, pinstripe top hat and the burgundy Mercedes-Benz in his photos that B really understood success. She was starting to fall in love again.

Without a word to her father or stepmom, the 33-year-old hopped in her 2002 green Volvo with $150 cash and headed down Interstate-5 South to meet the glamorous life waiting for her in San Francisco.

She was in for a whirlwind ride. But not the one she imagined.

"I didn't expect to be somebody's slave."

A Fleeting Choice

When Tucker pulled the Volvo into San Francisco, her heart was full and her hopes high. A new man, new dreams and the belief she would soon get her kids back.

It didn't hurt that B was as handsome as she imagined.

He was a muscular man in his 30s, with a neatly-groomed goatee. He dressed in crisp button downs, True Religion jeans and beige alligator leather shoes. A gold cross necklace dangled to his waist. When he smiled, the three-karat diamonds in his 24K gold grills shone.

There was a crown tattooed on the left side of his neck. Every time he left, he told Tucker to "kiss his crown."

She would later learn all the pimps who "owned" girls had crown tattoos — a badge of honor on the streets and in the industry.

She may have been 33, but she was terribly naïve.

She wanted to believe B loved her. She thought they were going to be partners. She convinced herself B held a key to a better life.

An all-too-familiar tale, says Boyer, the sex-industry expert.

"That is often the story, and then once that exploiter has her confidence, he completely changes and starts to control everything because the only thing that matters to him is money," Boyer said.

Tucker discovered the truth about B the first day she got there. He met her in the San Francisco motel room he booked in her name, but he told her he legally couldn't stay the night. That's because he had to return to a halfway house every evening. It's where he was required to live for six months on his way out of a 30-month federal sentence for forcing a Utah woman to work as a prostitute in several states.

But B always knew just what to say. He was smooth. He chalked it up to a life lesson. He was a changed man, he told her. And Tucker was a woman in love.

"He told me he learned that all the 'extra' (beatings and disrespect) was unnecessary and that treating a woman nicely would gain more respect. He said he would never be interested in having a corral of women again," she said.

"Deep down, I hoped everything would be OK."

Photo: Jennifer Tucker takes a selfie in an Oregon motel room on her way to meet B in September 2010. (Provided)

Photo: Jennifer Tucker takes a selfie in an Oregon motel room on her way to meet B in September 2010. (Provided)

Besides, even if she wanted to go back home, she didn't have any money to get there. B charged Tucker a $1,600 "choosing fee" to be his girl. She made that money on the road to California, picking up johns in Portland and Eugene, Oregon.

It was a pittance to pay, she thought, for his promise to help her get her kids back.

"He was always trying to make you feel better, but he could cut you real quick with two words," she said. "One minute he was all loving and romantic and the next minute, he was calling you a bitch."

With B, she morphed into "Mercedes." He named her after another prized possession: His car.

The mom who once dressed in modest sweaters and sweatshirts with her son's football team mascot became a woman for sale in risqué bustiers and thongs.

Her first customers in San Francisco booked her online because she was afraid to find her business on the street.

But that wasn't the way B worked.

"I was trying to tell (B) to post me on (Backpage.com) because that's what I was comfortable with. But he always thought that's what a 'lazy ho' did," she said.

B dropped her off on Long Beach Boulevard, a north-south thoroughfare in Los Angeles County. Over the phone, he trained her to walk "the blade" — a term used in the sex trade to describe areas of town that are known for prostitution.

On a busy day, she'd take in $2,000 from five to seven customers. She wasn't allowed to charge less than $200 for a half-hour trick.

"He said, 'I don't care what you have to do to get that money, and if it's any less, we're going to have a problem,'" Tucker recalled B's words, mocking his raspy, high-pitched voice.

Photo: Jennifer Tucker poses as Mercedes in this photo, which she posted online in an ad for her services. The image has been edited for nudity.

Photo: Jennifer Tucker poses as Mercedes in this photo, which she posted online in an ad for her services. The image has been edited for nudity.

Tucker didn't get to keep a penny of those payments.

B collected the cash and dashed any hope she had of ever getting her children back.

"I was pretty hopeless at the time, so rather than fixing a problem, I just checked out."

B bought a powder blue Jaguar convertible and a Rolex watch with the money she made.

He gave her just enough to pay for her cell phone bill each month. And he also gave her the $65 to pay for the matching crown tattoo on her left hip that signaled to other pimps that she belonged to him.

Hers said "PB," which stood for "Pimpin' B."

For Christmas, B bought Tucker some Coach perfume and makeup. They slept together, and that physical contact gave her worth, she said.

"Just talking about him, I can still feel my loyalty to him," Tucker said.

She wanted so desperately to please B.

Eventually, the money she brought him wasn't enough.

"He said, 'If you want to make things better then go find someone else. I had to find a 'friend,'" Tucker said.

She recruited "Diamond," a 25-year-old woman from Seattle, to join them. Diamond was B's birthday present. Tucker trained the girl how to work.

She didn't want to find out what would happen if she disappointed B again.

The first time she let him down, he slammed her up against the mirror of their hotel.

Though, she was forced to work against her will long before B put his hands on her. Tucker was just too blinded by love to notice.

Experts say many survivors of prostitution never self-identify as sex trafficking victims, even though they frequently become so while working in the sex industry. Federal law defines sex trafficking as "the recruitment, harboring, transportation, obtaining, patronizing or soliciting of a person for a commercial sex act." It's considered a federal crime when the sex act is motivated by force, fraud or coercion, or if the person is under 18.

Often times, pimps become traffickers, but federal and local trafficking convictions are relatively rare. People in prostitution often form trauma bonds with their exploiters, and that leads them to misunderstand their own exploitation. It's easier for prosecutors to take traffickers down on different or lesser charges because victims are more likely to be loyal to their exploiter than the criminal justice system, experts say.

"Some people recognize (what's happening), but coming to terms with what it would take to get out of that situation, it's easier to put it out of their mind," said Robert Beiser, executive director of the anti-trafficking group, Seattle Against Slavery.

"This might not be the worst thing that happened to them," he added. "So they can live through this, and maybe there are some benefits to it, even though it's really horrible."

B never put his hands on Tucker again. But once was enough to give her the courage — but not yet the means — to flee.

That wouldn't come until after she stood in a vineyard, with the barrel of a 12-gauge pistol grip shotgun shoved down her throat.

Escape

Tucker was in tears the December day she decided to leave B, the man who had once promised so much and given so little. The man who destroyed any hope that she would get what she wanted more than anything else: Her children and a future.

But in this breakup, there was no family or another support system to get her through it — only the customer who helped her sneak away from B after he became angry with her for spending the money she earned that day on food. The customer picked her up after a full day of tricks on Long Beach Boulevard and took her closer to the Greyhound bus station.

"I left because I knew once B hit me that he would never love me the way he said he did," she said.

That weekend, Diamond drove 33-year-old Tucker around so she could meet with "johns." One customer was waiting for her at a fancy vineyard in Santa Rosa, where she knew she would make a lot of cash — maybe even enough to leave the state.

"About 30 minutes into the 'date,' I started seeing men with heavy artillery on the security cameras," Tucker recalled. "Then he took me into the bedroom."

The blond man was a leader of a biker gang who had a close relationship with local pimps. He shoved the barrel of the shotgun down her throat before he raped her, she said.

"'B told me to tell you hi,'" Tucker remembered the man's words. "He said, 'Either you work for us, you work for him or you get out of our city.'"

She never told the police.

"Had I done that, it would have either been my life or my freedom. How do you go to the police and tell them you were assaulted while selling your services?" she said.

Fleeing California would have been the perfect moment for Tucker to start over; in theory — a chance to leave the life she was starting to hate.

But she got hung up on a simple, yet deeply complicated question that keeps women like her trapped every time: Where would she go?

"Usually women are paying for a hotel — a place to stay from night to night so they don't have any place to go," Boyer, the sex trafficking expert, said. "They have been out of school, they don't have job skills, their families have not been supportive. They don't have any alternative way to make a living and to support themselves."

In exchange for Tucker's services, one of her regular customers agreed to give her a place to stay for a few weeks and some extra money so she could leave town. Headed south, she left Diamond behind and picked up customers from state to state. She was on a mission to make enough money to send Christmas presents to her two oldest kids, living with relatives in Texas.

Even though she escaped the man who controlled her, she was far from safety.

"When you're broke down to nothing, you don't see any options. Honestly, I didn't even have the strength — emotionally or mentally — to survive on my own," she said.

That's why when her car broke down in Mississippi on the way to Texas, Tucker said she ran to the next pimp who offered to help.

"You kind of get a sense of comfort in having something that's familiar," Tucker explained.

This man paid for her bus ticket to Beaumont, Texas, where he picked her up and took her to his gated townhouse in Houston.

He was nicer than B. He didn't beat her. Plus, when she brought in enough money, he'd give her his time.

That's all she wanted, really — someone to fill the lonely void.

Sometimes, he'd even bring her to his mom's barbecues.

'Trafficked By The Customer'

While Tucker loved the pimps who stole her hard-earned cash, she despised the customers who paid for her services.

"I think you can be trafficked by the customer. Y'know what I mean?" she said, as if the epiphany hit her right then.

"You're just as much at their will as you are with any pimps when you're with them."

Every time a customer left her motel, she would soak in the bath. But in a twisted way, the same men gave purpose to the lifestyle she couldn't kick.

"I used to justify it by saying I was taking perverts and child molesters off the streets," she said.

Her customers ranged from young, lanky businessmen to 450-pound and 85-year-old men.

"Executives...people who were going to churches, military guys, colonels, regents," Tucker rattled off their occupations.

As she moved from state to state — 10 in total, she started using crystal meth. That was the easiest way to mask the shame of some things her buyers would make her do, she said.

There was the man who would pay her to suck her toes.

Another who once tied her to a cross and took pictures.

Another who paid her $1,700 to spank him with a belt.

Then there was John, a 46-year-old man who fell in love with her. He told her he was ready to leave his wife.

But none of those customers made her feel more uneasy than the men who compared her body parts to the young girls they raped.

She was always prepared for the "dates" to turn dangerous fast.

In Texas, one customer robbed her at knifepoint after he raped her for hours, she said.

She stayed, succumbed really, because the money the men paid her was "too good" to pass up.

Until one day she realized it would never be enough to buy her Texas pimp's love.

A Renegade's Life

At 34, Tucker ran away from her Texas pimp and hopped on a bus back to Washington.

She was tired of competing for his attention with the three other women working for him.

"He promised a relationship and all he did was use me," she said. "I wanted to be loved."

She contemplated getting a different job. She even applied for a few.

"Office, coffee, restaurants. I had a resume," she said. "Problem was, I couldn't explain what I had done for work since 2010."

Tucker couldn't explain it to her family either.

She didn't want her father to know she was a prostitute. Addicted to drugs, she couldn't imagine being welcomed back into his faith-filled home.

"The shame that comes along with being in 'the life' becomes debilitating," said Marin Stewart, a prostitution survivor and a Friends of Youthadvocate for sexually exploited youth. "It literally shapes your view of the world, shapes your view of relationships, shapes your view of men and women and shapes your view of yourself.

"It makes it very, very difficult to see outside of the life that you have completely immersed yourself in," Stewart added.

So Tucker went back to the life of paid sex work.

She became a "renegade." It's a prideful term prostitutes use to describe themselves when they work without a pimp.

"You can remove the pimp, but that behavior can still be within the person," Stewart said. "It's so deeply ingrained in them that 'this is what I need to do to provide for myself. This is what I need to do to keep up my (drug) habit. This is what my self-worth is. I am good at this."

Tucker made a name for herself with buyers spanning from Everett to Tacoma.

"I moved around a lot,” she said. “You don’t want to stay in one spot for too long because then you’ll get caught, y’know?"

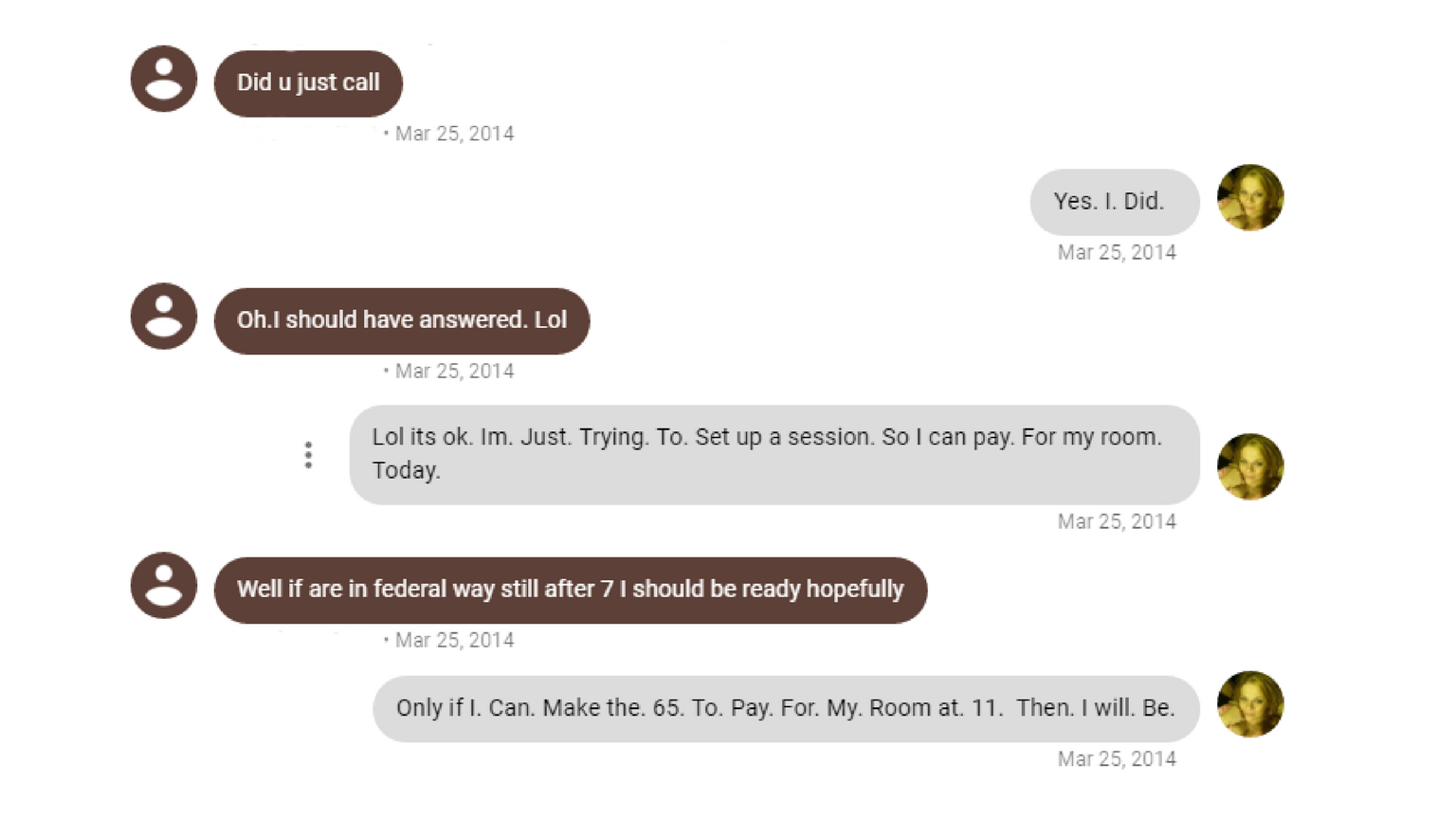

Some nights, though, she had to beg for business. It was the only way she could afford a place to sleep.

This time, heroin — not a pimp — stole her cash.

A boyfriend introduced Tucker to her new favorite vice.

'I Was Always Stopped'

By 2014, the inside of a jail cell was almost as familiar to Tucker as the motels she rented each night.

“The first time I was arrested (for prostitution)…. (the cops) recognized my face from my online ads,” she said. “And then it was just all downhill from there.

"I was always stopped (by police).”

Experts say it's common for prostitutes to face a life in and out of jail, usually for crimes they commit to please their pimps or to support a drug habit.

"Often times, people don't go into this (industry) addicted (to drugs)," said Boyer, the Seattle-based sex trafficking expert. "They will start using drugs to numb themselves, to get themselves through it. And then they have compounded the problem."

Tucker had been arrested across the country so many times, she lost track of all the reasons why.

She faced charges in Washington for crimes ranging from prostitution loitering and third-degree theft to identity theft and felony drug offenses.

Each time she got out of jail, she spiraled deeper into a state of despair.

“I hated everything about my life. I wanted to be a mom again...be part of a family. I hadn’t talked to my family in two years,” she said.

But Tucker's dream of getting her kids back was already squashed. She lost that hope the moment B broke his promises.

In May 2014, 36-year-old Tucker was caught again — arrested this time on a felony drug charge for possessing crystal meth. Police found her kneeling on a plastic bucket with a glass pipe in her hand. She was with a boyfriend, hiding between large shipping containers in a Fife parking lot.

A Pierce County judge released Tucker from jail but ordered her to complete felony drug court. She had to show up for a monthly court review hearing, attend group sessions twice a week and take random drug tests.

But in February 2015, Tucker stopped showing up.

“I stayed sober for a while until I just couldn’t,” she said. “It was too much to still be working in the industry and not getting high.”

Police issued a warrant for her arrest.

But hundreds of strangers found her first.

Independent Prisoner

The day that everything changed began like all the rest.

Now 37, Tucker woke up in a Federal Way motel bed and smoked two-tenths of a gram of heroin that May morning in 2015 so she could "get well."

Photo: Tucker woke up in this motel on May 16, 2015. (Taylor Mirfendereski | KING 5)

Photo: Tucker woke up in this motel on May 16, 2015. (Taylor Mirfendereski | KING 5)

With her long leopard print nails, she fastened her denim daisy duke shorts and dug out a sequined black tank top from the black and cream leather backpack she carried all her belongings in. She pulled her arms through the straps of her shirt, leaving her now faded Mercedes tattoos on full display. Then, she waited for her customers to arrive at her first-floor room off of Pacific Highway.

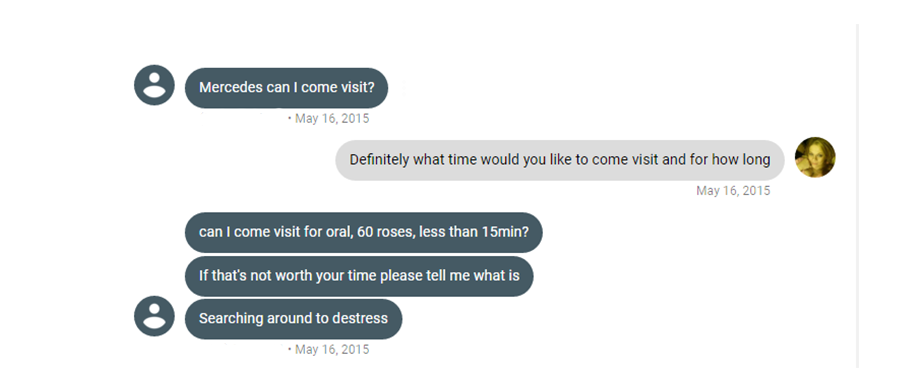

Photo: A screenshot of Jennifer Tucker's text conversation with a customer on the morning of May 16, 2015.

Photo: A screenshot of Jennifer Tucker's text conversation with a customer on the morning of May 16, 2015.

She had two different appointments that morning, scheduled with men who requested oral sex.

After the men left, Tucker put her clothes back on. She checked out of the motel and walked to the bakery next door with her bags, wearing thigh-high black leather boots.

All she wanted was an iced mocha before moving to the next motel across town. But hundreds of people marching on the sidewalk in green shirts stopped her in her tracks.

"These people had signs that said 'I'm not for sale' and 'you're valuable,' 'you're wanted,' 'you're loved,’” she said.

Photo: People march down the sidewalk with signs on May 15, 2015 in Federal Way. (Provided | Brenda Oliver)

Photo: People march down the sidewalk with signs on May 15, 2015 in Federal Way. (Provided | Brenda Oliver)

It was an unusual sight on this stretch of Pacific Highway, where Tucker ran into “junkies and prostitutes” more than people who weren’t in "the life" of paid sex work.

"I think people just overlook us, y'know? It's just another crime being committed, and they don't realize how desolate the people that are stuck are," she said. "I didn't even value myself so to even imagine that somebody else valued me was pretty hard to wrap myself around."

Still, she couldn't help but think maybe, just maybe, there was finally a way out.

“I was tired of having to make such a big sacrifice," she said. "I mean, every time you go on a date, you are putting your life at risk.”

In the crowd, Tucker spotted and walked up to two older women wearing glasses.

They reminded her of her mom.

“I asked, ‘What is this about?’” she said.

The women were marching in an annual 5K called “Break the Chains,” organized by the Federal Way Coalition Against Trafficking. They chose that particular stretch of the Federal Way highway to reach prostitutes who were working and living in motels.

Photo: A crowd bursts through a paper chain at the start of the Break the Chains 5K fundraiser on May 16, 2015 in Federal Way. (Provided | Brenda Oliver)

Photo: A crowd bursts through a paper chain at the start of the Break the Chains 5K fundraiser on May 16, 2015 in Federal Way. (Provided | Brenda Oliver)

“They told me they were raising awareness for sex trafficking and (were letting) people in the industry know that they were loved and that there were other options,” she said.

Tucker started to sob.

“They made me feel cared for, not as a hooker but as a person — as Jennifer," she said. "They could see my past — what I did — and they still cared."

It had been nearly four years since Tucker drove that green Volvo to San Francisco. And this was the first time "normal" people made her feel normal, too.

“I think at that moment is when I decided I was going get out of 'the game,’” she said. “That was like my goal — to be able to win. To get out of it and stay out of it.”

The women asked Tucker to walk with them.

She didn't.

Because in her mind, she couldn't. Tucker's thoughts gripped her tighter than physical chains.

"I was like 'No, I'll be a hypocrite because I know what I'll do tomorrow," she said.

It would take nine more months — and a cop — before she could walk away from this life.

“It’s hard for the average person to understand. It’s kind of like when you’re in an abusive relationship...and people ask, ‘Why is she still there?’ Y’know? ‘He beats her every week until she’s almost dead. She’s so stupid. Why is she still there?' There’s a reason she’s still there,” she said.

“Everyone thinks only the ones who are pimped are captive. No, it’s everybody. It’s a bondage that’s probably one of the most difficult to break."

The anti-trafficking march couldn't break that bondage. But the two women cracked Tucker's hardened shell — all because they cared.

"(After that day,) I would come out of my dates crying," she said.

"I was just trying to find a way out really."

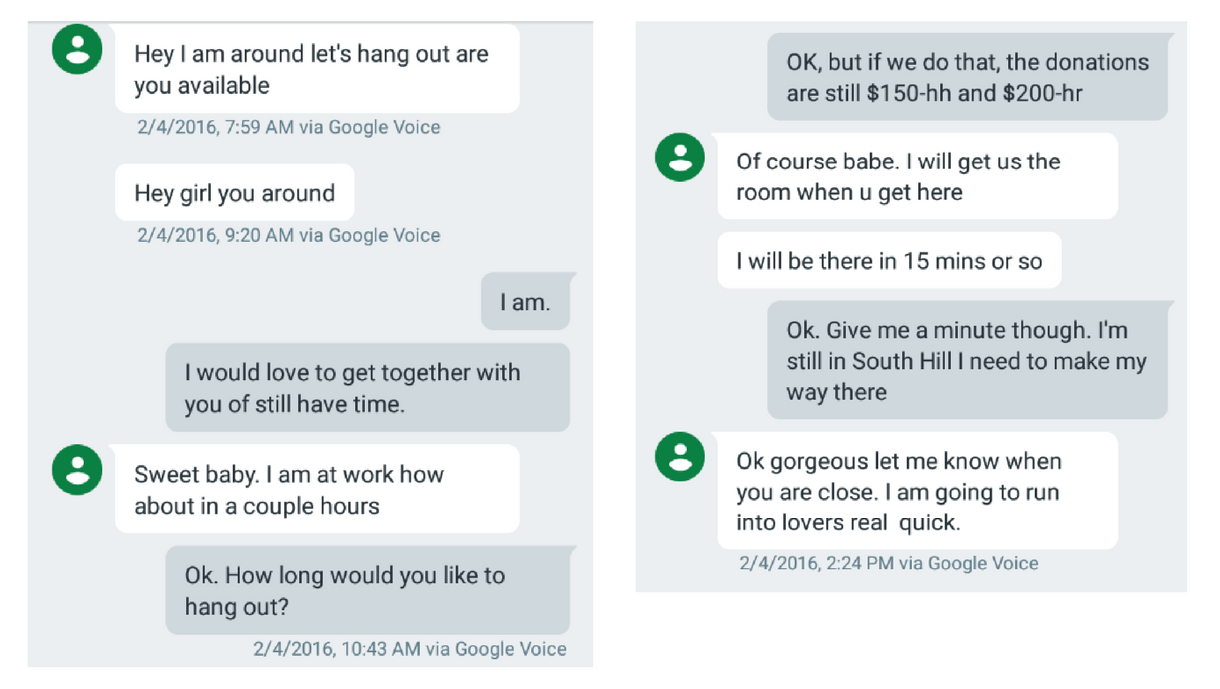

On February 4, 2016, Tucker showed up to a Tacoma motel. She had an appointment with a man in Room 208.

"I went to put my hand around his waist, and I felt his .45 cal pistol on his right hip," she said.

"I looked up and said 'Oh man.'"

She knew her customer was a cop. Instead of cash, he had a warrant for her arrest.

She went to jail for four and a half months, finishing up the remainder of her sentence for a 2014 felony drug charge.

"God got a hold of me when I was in there, and it just changed everything," she said.

Adjusting to her new life on the outside was a challenge she wasn't prepared for.

A New Normal

Bill Tucker couldn't take his eyes off his sober daughter the morning he picked her up from jail in June 2016.

So he took her to McDonalds to share a cup of coffee.

"It was the first time she had looked healthy in a long time," he said. "She had color in her face. She didn't have (meth) sores. Her hair was not matted. It was actually shiny. It had a gloss to it."

It was a stark contrast from the daughter he stumbled on in a Pierce County jail log when he was frantically searching for Tucker years earlier. That was the same day he learned she was a prostitute. It was the day he Googled her working name, Mercedes, in disbelief.

"I just balled. I stood in front of the computer and just stopped. That was my little girl, y'know? I just did not want to lose her," the elder Tucker cried as he described the sexual images of his daughter that popped up. " I just felt desperate. I knew that the only way I could get her back was through the power of God."

Now he finally had his youngest, 38-year-old daughter back in his home — at least her physical shell. And she wouldn't be leaving Pierce County anytime soon —not without a permission slip from her community corrections officer.

Tucker traded in her working name, Mercedes, for Jennifer, her given one. She swapped her sexy lingerie for a closet full of baggy sweatshirts; heavy makeup for a natural look. She sold all of her heels and leather knee-high boots on E-bay.

She joined a Tacoma church and started to volunteer. She became a live-in nanny for a family she met there, and she took a second job as a barista so she could go back to school for a theology degree.

She even reunited with her two oldest kids, who she had rarely seen since they went to live in Texas.

But inside, Tucker struggled.

"I think the hardest part is like — it's not the being done (with prostitution) part. It's just fitting in with 'normal' people," she said. "Knowing who you were and wondering if they know who you are."

"It was like debilitating. I'd go into a crowd of people, and I just couldn't move," she added.

Photo: Tucker prepares a woman's order at a Tacoma cafe. (Taylor Mirfendereski | KING 5)

Photo: Tucker prepares a woman's order at a Tacoma cafe. (Taylor Mirfendereski | KING 5)

She didn't miss working as a prostitute. But she missed the people from her old life — occasionally, even the men who sold her.

"I went through a lot of loneliness. Like, you have to grieve the loss of an old life, even though it was a hard life," Tucker said.

Prostitution experts say that's one reason prostitutes who try to leave the sex industry struggle to stay out for long.

"When you're trying to leave that life behind you, usually the people you've surrounded yourself with don't celebrate you leaving," Stewart, the prostitution survivor and victim advocate, said. "It makes them have to think about where they are. You're constantly being pulled back there because of the whole thing about 'misery loves company.'"

Photo: Jennifer Tucker (Taylor Mirfendereski KING 5)

Photo: Jennifer Tucker (Taylor Mirfendereski KING 5)

The first time Tucker convinced herself to hang out with "normal" people, she bumped into an old customer at a church party. He was sitting with his wife and two kids.

Tucker was fully clothed, but she felt more naked and exposed than the day the man bought her in Federal Way in 2013.

She froze.

The man ignored her. He carried on with his family as if he'd never purchased sex before.

Tucker didn't just physically bump into old customers. They still called and texted daily, responding to the hundreds of online escort ads for "Mercedes" that she couldn't delete.

Pimps contacted her, too.

"They wouldn't stop," she said.

Tucker couldn't bring herself to change her phone number. She was too afraid to let go of the last tangible thing that tied her to her past life. Plus, she justified, her youngest kids in Brazil used that number to call her.

On November 30, 2016 — 5 months and 12 days after her dad picked her up from jail — Tucker relapsed on drugs.

She got high on crystal meth. It happened on a day she decided to hang out with old friends.

"When I think about going around certain people, the first thing that goes to my mind is 'If I slip, I'll be OK,'" she said. "As an addict, your mind goes into self-preservation mode. 'How do you avoid these feelings?'"

That was the last time Tucker said she used drugs. She spent 15 days in jail for failing her monthly court-mandated drug test.

She cut off most of her old friends after that, but she still had to deal with customers who wouldn't stop texting her.

"I'm very sorry to hear that you're not working anymore," one customer wrote. "If you ever change your mind, I would love to meet you. I think you look beautiful."

One day, Tucker decided to respond.

"I told them how purchasing a girl doesn't benefit them. It actually tears them down, and every time that you pay for a girl's services, you're contributing to their demise. You know, 'cause it takes away your self-confidence. It takes away our worth. It devalues us," Tucker proclaimed, with pride.

"I was pretty proud when I told them how it makes a girl feel," she added.

It was a victory for Tucker.

Experts call her a survivor.

Tucker didn't see herself that way.

"I'm an overcomer," she said.

Full Circle

With the sun beaming, Tucker sheds her black RECOVERY sweatshirt as soon as she gets to Pacific Highway.

A volunteer hands her the orange 5K t-shirt. She puts it on and rolls up the sleeves.

It's too hot to keep her Mercedes tattoos covered up.

She twirls her ponytail into a ringlet, waiting for the race to start. The Federal Way mall parking lot is filled with families and church groups — dogs, moms with strollers, high school students and runners decked out in brightly-colored tutus.

Tucker looks from left to right, searching for something, for anything, familiar.

"I'm here by myself, representing myself." she says, introducing herself to a small group of women. "I don't know anybody here."

She finds an odd solace in the company of these women, who tell Tucker that they're representing their relative, Danica Childs. In 2009, the 17-year-old disappeared after she was seen at a Kent motel associated with prostitution.

She asks the women if she can walk with them. It would be unsettling to walk past her old stomping grounds alone, she thinks.

A man blasts a horn at the starting line, as dozens burst through a chain made of purple construction paper.

Tucker pops in her earbuds.

She begins to hum gospel music as she cheerfully walks down Pacific Highway with her new friends who are holding signs.

Photo: "Team Danica" walks down Pacific highway during the Break the Chains 5K fundraiser in Federal Way on May 20, 2017. (Taylor Mirfendereski | KING 5)

Photo: "Team Danica" walks down Pacific highway during the Break the Chains 5K fundraiser in Federal Way on May 20, 2017. (Taylor Mirfendereski | KING 5)

"I feel better now that we're around a bunch of people," she says. "It's kind of nice knowing that there are people who understand (me)."

It's strange walking alongside traffic again. It reminds her of the days B forced her to walk up and down the blade.

Tucker stops humming.

She lets out a heavy sigh as she walks past something familiar.

"You doing OK?" Danica's aunt asks.

Tucker points to a rent-by-the-hour business.

"Like, right there is where most of the business goes on — in that little sauna place," she says.

Barely a year ago, Tucker spent countless hours inside there with her customers.This was the first time she saw it from the outside.

Tucker gets a second wind as the group nears the motel and bakery where everything changed that May morning, two years ago.

"I'm kind of hoping there are people out there," she says. "Y'know, (people who will) see it like me."

Maybe she'll run into a prostitute she can help, she thinks. Just like those women helped her realize there was life after prostitution.

But when she finally makes it to that spot, there's not a pimp or a prostitute in sight.

Still, she's beaming with pride and nostalgia. She whips out her cell phone to share her milestone with friends and family.

"So this is about where it all began," she broadcasts on Facebook Live, describing the 2015 encounter in detail.

Photo: Tucker talks to her friends and family members on Facebook Live as she approaches the finish line of the Break the Chains 5K fundraiser in Federal Way on May 20, 2017. (Taylor Mirfendereski | KING 5)

Photo: Tucker talks to her friends and family members on Facebook Live as she approaches the finish line of the Break the Chains 5K fundraiser in Federal Way on May 20, 2017. (Taylor Mirfendereski | KING 5)

In the distance, she sees dozens of cheering supporters line the sidewalk.

At that moment, the 39-year-old thinks of every goal she set in her life.

There were only two.

The first one was to get her youngest kids back. She failed miserably.

But now, she is feet away from her accomplishing her second.

She jolts through the screaming crowd of supporters, high-fiving her way to two women — one who organized the race.

"You did it!" they shout.

Tucker wraps her arms around the women. She begins to cry.

Thousands of customers, 10 states, six years, three pimps.

And one finish line she never expected to cross.

Photo: Jennifer Tucker smiles after walking across the finish line of the Break the Chains 5K in Federal Way on May 20, 2017. (Taylor Mirfendereski | KING 5)

Photo: Jennifer Tucker smiles after walking across the finish line of the Break the Chains 5K in Federal Way on May 20, 2017. (Taylor Mirfendereski | KING 5)

Epilogue

It's four days later, and Tucker is propped on a chair in a Tacoma tattoo parlor.

Tucker realized she couldn't erase her tattoos any more than she could her previous life.

"I could totally keep all of my life in the past and just pretend like it didn't happen," she said. "But that would make 39 years of my life spent in vain."

Tucker winced as the tattoo artist spelled the word in red ink across the Mercedes symbols on each shoulder.

"Forgiven."

Dig Deeper: Video Story, Panel Discussion

WATCH: Jennifer Tucker's Journey

The below video story aired on KING-TV on Oct. 25, 2017.

WATCH: A Conversation On Sex Trafficking

Tucker joined KING 5's Taylor Mirfendereski and Mark Wright on Oct. 26, 2017 for a live audience-driven discussion about understanding and ending the cycle of sexual abuse. Other panelists included Allison Jurkovich, director of advocacy services for the Organization for Prostitution Survivors and Emily Glassert, a clinical therapist at the King County Sexual Assault Resource Center.

If You Need Help

The national hotline for human trafficking victims is 888-373-7888. Call this number to report a tip or to request services.

We've also compiled a list of Washington groups that provide support to prostitution survivors and sex trafficking victims as they recover from their experiences.

How This Story Was Reported

KING 5 followed Jennifer Tucker over the course of four months. Details in this story were taken from police records, court documents, text messages, voicemails and escort ads, in addition to interviews with Tucker, victim advocates, service providers and prosecutors.

This story is affiliated with Selling Girls, a nine-month nationwide investigation into sex trafficking. TEGNA, our parent company, launched the project at each of our 46 stations across the country to help hundreds of thousands of American kids who are lured into a life they didn't choose. To watch the six-part series and to follow KING 5's ongoing local coverage of sex trafficking in Washington state, click this link.

Contact The Reporter

Taylor Mirfendereski is a multimedia journalist, who focuses on in-depth reports for KING 5's digital platforms. Follow her on Twitter @TaylorMirf and like her on Facebook to keep up with her work. For story ideas, e-mail her at tmirfendereski@king5.com.