RENTON, Wash. — Of all schools in the state of Washington – including public universities, community colleges, and public and private trade and vocational schools – no school has been paid more by the state Department of Labor and Industries (L&I) to retrain injured workers than a small, private, unaccredited, mostly online school located in a business park in Renton: Office Careers.

For disabled workers who cannot return to the job where they were injured and don’t have skills for a different line of work, state law allows L&I to authorize retraining. Worker compensation dollars pay the tuition.

There’s a lot on the line. If a disabled worker goes through retraining and earns a certificate or diploma, L&I can find them “employable” and terminate all their benefits.

At issue is whether or not Office Careers actually offers a program that leads to injured workers obtaining jobs, and whether or not the school simply passes people through the program regardless of their ability to do the work.

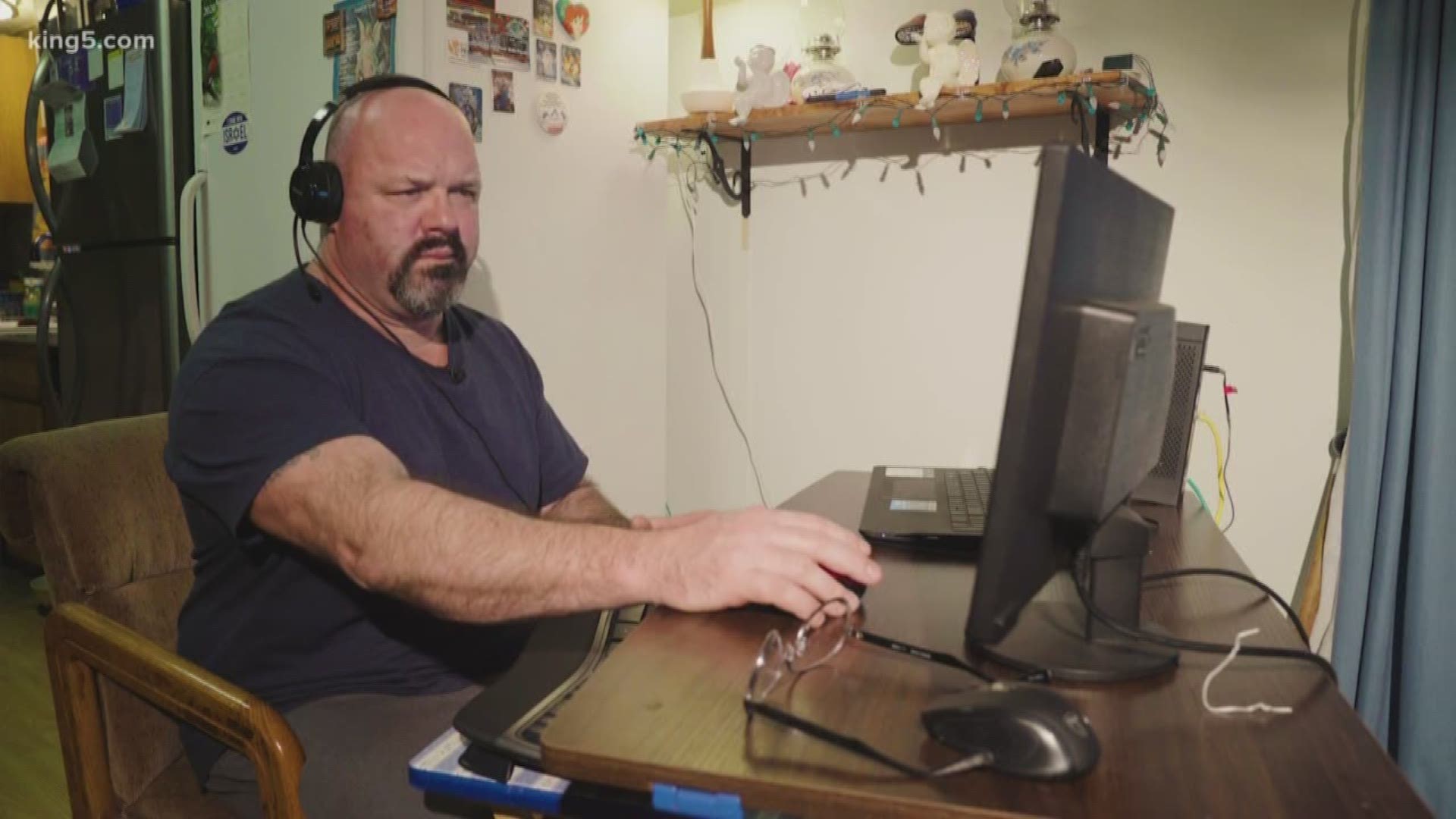

Joe Cheyney, of San Juan Island, is a current Office Careers student. The 54-year-old was injured on the job working as a meter reader for the public works department of the City of Friday Harbor. A work-related car accident in 2012 left him with a crushed left knee, and head and back injuries. He said his state-paid vocational counselor insisted he attend the year-long retraining program at the online school to learn the skills to become a secretary. The state paid the $13,800 tuition.

“There’s no way I can be a secretary. I have disabilities. Learning disabilities. I have dyslexia… I hate computers,” explained Cheyney.

Cheyney said he feels he’s failing miserably at the training. Four months into it, he is still typing at just five words a minute. Cheyney doesn’t complete assignments and said he can’t retain the information. Office Careers doesn’t administer tests, but they submit progress reports to the state’s vocational counselors. In Cheyney’s case, the reports look promising.

In a report dated December 2019, the counselor wrote that Cheyney "is currently performing well and putting forth effort.”

Another report in January documented that Cheyney “[is] going slow – he’s a few weeks behind because of his difficulties seeing the screen…His typing speed is very slowly improving…we can soon…get him back on track.”

The counselor ended the report saying, “Mr. Cheyney is progressing as expected.”

“It’s a joke,” said Cheyney. “I’m trying. I’m working my best at it, but I just don’t get it. I’ve told [the school’s teacher and state counselor] multiple times that I can’t do it. [But] they just keep passing me and keep pushing, ‘Oh, you can do it. You can do it. You’re doing fine.’”

Cheyney isn’t alone. The KING 5 Investigators have interviewed or reviewed the case files of 30 former Office Careers students from around the state. Of the 30 disabled workers, all but two said they were pushed through the program, whether they learned the material or not. The former students said they didn’t take any tests to get into the school, or any tests to show they had actually learned any skills. The 28 students with negative experiences said they left the training with a certificate but no skills, no job, and no more benefits from the state.

“I got shoved into it [by the state-hired vocational counselor],” said 75-year-old Beverly Wasson, of Whidbey Island, who got a certificate from Office Careers in 2013. “I felt like at the end I didn’t know any more than when I went into the class. It was just a joke. There wasn’t much interaction with the teacher. I was copying stuff on the computer. I made a lot of mistakes and didn’t know how to type…There’s no way I could get a job in an office.”

Fifty-seven-year-old Cyprian Amadeo, of Lakewood, said he couldn’t do the schoolwork, yet he got a certificate anyway, which led to the loss of benefits and deep depression.

"I didn’t know what was going on [in the training]. I couldn’t do it and I have no idea why they sent me a certificate,” said Amadeo, who was injured at work in 2007 when he fell down a flight of stairs. “[After Office Careers] I got depressed. I was going to food banks to feed my family. I would be crying getting food because I felt helpless, like my whole life has been destroyed and nobody cares. I thought I would be better off dead.”

Rich Wilson is the private sector compliance manager for L&I who oversees the injured worker retraining program. He said they continue to pay for students to attend Office Careers because the state has never had any concrete evidence of wrongdoing by the school.

“The laws governing L&I and the schools we can deal with say if you’re licensed or accredited you can be on L&I’s list,” Wilson said.

Office Careers put KING 5 in touch with the two students who had positive experiences. Of those, one of them is employed full-time as a vehicle dispatcher, which is the program he studied. The other student said she’s applied to between 30 to 40 jobs to be a medical coding and billing clerk, but so far has not landed employment in the field.

“[Before Office Careers] I was completely computer illiterate,” said Cathy Reeves, of Medical Lake. “They were there for me. They were good to me. I was satisfied with Office Careers.”

Reeves, who was injured on the job at Eastern State Hospital when a psychiatric patient punched her repeatedly in the head, continues to apply for medical coding and billing clerk jobs.

Retraining injured workers is big business in Washington. An analysis of state financial records showed in the last 10 years, L&I has paid more than $70 million to dozens of schools for tuition and fees. Office Careers has been paid the most in that time period at $7.4 million, followed by Edmonds Community College at $5 million, Clover Park Technical College at $4 million, and Everett Community College at $3.6 million.

Unlike those schools, Office Careers is not accredited and doesn’t track if their students obtain jobs after obtaining a certificate. Many schools publicly report the percentage of students who are employed in the field of study.

Of their medical coding and billing students, Everett Community College reported 65 percent get hired within six months of program completion.

Edmonds Community College reported 80 percent of its office supervision and management program students land jobs within six months.

Wenatchee Valley College reported 74 percent of its students earning a business program certificate, which centers on learning the Microsoft Office suite applications, obtain jobs within six months.

David Jordan, the owner of Office Careers, defended his school, which has offered training since 1991. He said most of his instructors hold master’s degrees and offer one-on-one attention students wouldn’t get at bigger schools.

Jordan pointed to the fact, confirmed by KING 5, that no student has ever filed an official complaint against the school with the state’s regulatory board that oversees private vocational schools.

“If there’s a problem, we’re not hearing about it,” said Jordan. "We have a quality program. We’re doing all that we can to prepare [injured workers] for work and we feel like we’re doing a good job with that.”

Jordan also said the state doesn’t require accreditation, only licensing, and that data on employment isn’t mandatory either.

“We’re not set up for [tracking outcomes] and not paid to do it,” said Jordan. “We don’t need to report that and it hasn’t been asked of us.”

A group of attorneys from the Washington State Association for Justice who specialize in worker compensation law and regularly meet with top L&I officials on issues regarding injured workers, said they’ve complained about Office Careers for years, but it has fallen on deaf ears.

“Colleagues and I and workers and others…have been raising concerns about Office Careers for at least as far back as 2007,” said Katherine Mason, a Seattle attorney who represents injured workers. “I don’t know why [Office Careers] gets a pass…it’s a waste of taxpayer dollars and they really get away with it year after year after year.”

Wilson of L&I confirmed the attorney group has brought complaints to him regarding Office Careers. He said that’s one of the reasons why, for the first time ever, L&I initiated an audit of a school. The review of Office Careers began in June and should finish in two months, Wilson said.

“This is how we’re going to get at facts, and in order to take action, we need facts,” Wilson said. “We are paying money and we can choose not to pay money if there’s a factual basis not to. That would be one option, to simply not use a school anymore, [but we’ve] never done that.”

The KING 5 Investigators went behind the scenes and observed four hours, over two days, of real-time online classwork with Cheyney. In those hours, KING 5 witnessed only 5 minutes of instruction from the teacher. KING 5 also looked on as Cheyney pulled up an assignment to finish that he said his teacher had already finished for him.

“I did not do that assignment. I don’t even know how to do that,” said Cheyney. “They actually change the work that I do right in front of me, and they put it into my file as if I did it. It’s very falsified. Somebody else’s work on the other end.”

Jordan of Office Careers denied his instructors do work for the students. He said they are most likely showing the student what to do, and that is getting misinterpreted.

“The instructors are not doing the student’s work,” said Jordan. “It doesn’t make any sense that it would be done that way, and that’s not how we do it.”

Cheyney said he’s worried the state’s retraining program will leave him in a hopeless situation: disabled, unemployable, and cut off from the benefits he’s entitled to under worker compensation laws.

“In my case, I would lose everything I own,” Cheyney said. “I can’t afford not to get a job when this [training program] is over.”

“They don’t care for the little people. They care for the big people. I’m sorry but that’s how I feel,” said Cheyney’s wife, Kat. “This is unfair. This is not right for any person in the United States, come on.”