State, federal and tribal scientists involved with the current relicensing of Seattle’s dams on the Skagit River say the utility has propped up “outdated” and “misleading” science about the hydropower operation, in an effort to avoid responsibility for disappearing Skagit salmon.

All salmon species in the Skagit River, where the city operates three dams, are in decline. Three species of fish are sliding toward extinction, including chinook salmon. But that doesn't mean the utility is to blame. The city’s research shows the dams are located above where fish would spawn and grow. Their studies indicate rugged geologic conditions would prevent migration of anadromous fish in the project area, even before the dams went in. Anadromous fish, like salmon, go out to sea to grow, then return to freshwater to spawn.

“We think we’ve looked at the data objectively,” said Jeff Fisher, senior aquatics ecologist and strategic advisor for Seattle City Light. “Those reports…they are essentially one of the lines of evidence that there were no observations of anadromous fish, anadromous salmon or steelhead in the upper basin (of the Skagit River).”

At issue is whether the utility will have to spend millions of dollars to build infrastructure to help fish get upstream and downstream of their dams under a new federal license. The license for the Skagit River Hydropower Project under the Federal Power Act will expire in 2025. The utility has asked for a new license to span 50 years.

Federal regulators have long shown that dams hurt fish by blocking off essential habitat. On the Skagit, Seattle City Light’s dams block off nearly 40% of the river’s habitat to salmon.

When relicensing talks began two-and-a-half years ago between Seattle City Light representatives and stakeholders, including state and federal regulators and three Indian tribes whose ancestors inhabited the Skagit basin for centuries, the city dismissed the idea of even studying fish passage under a new license because their science showed the dams were built above natural fish barriers. The most significant barriers, according to the utility’s filings with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), which licenses hydropower projects, are massive boulders and steep canyons in what is known as the Gorge Bypass; a 2.5 mile stretch of the river between Newhalem and Gorge Dam in Whatcom County.

The KING 5 Investigators have found the three main studies the city referenced approximately 50 times in its initial filings to the FERC were produced 32, 33, and 100 years ago, respectively.

“Smith and Anderson, 1921” is a 104-page report that includes observations by a University of Washington assistant professor of zoology and one of his students as they boated through the Skagit and its tributaries. They noted “low falls and rapids” that would inhibit salmon from migrating upstream.

Smith and Anderson included several interviews of locals in the report who said they’d “never seen salmon more than a mile above (what is now the town of Newhalem).”

On the first page of the report, the authors’ boss discounts the thoroughness of the findings.

“The survey must be considered as superficial. It would take very much more time than was spent to make anything like a thorough investigation of the waters covered,” wrote John N. Cobb, Director of the University of Washington School of Fisheries.

Government, tribal and non-profit scientists criticized the city’s reliance on the report.

“One hundred years later, we can do better,” said Tom O’Keefe, aquatic ecologist and Pacific Northwest stewardship director for the non-profit American Whitewater. O’Keefe is also a member of the Environmental Advisory Board for Seattle City Light. “We need to shift from this place of just looking at stories from 100 years ago and pivot to the quantitative studies that can be informed by that. We need to reflect a modern understanding of how fish move up and down river systems and what we need to do to quantify that.”

The city also points to two studies conducted in 1988 and 1989 by their paid consultant, Envirosphere Company.

The 1988 report includes a collection of interviews from homesteaders, locals and Seattle City Light employees. Homesteader Glee Davis reported, “There’s an awful lot of rapids, (below the dams),” and that “salmon never make it to a place like that.”

A Seattle City Light train conductor reported not seeing many anadromous fish past the Gorge Bypass.

“To the best of his knowledge, only a few steelhead have ever made it past (the barriers),” wrote the authors.

The managing biologist for the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe, Jon-Paul Shannahan, said the 1921 report and the Envirosphere Company research is misleading and should not be used in making decisions on what will happen on the Skagit River for the next 50 years.

“(Their science is) no good. It’s old. It’s not true,” Shannahan said. “(Seattle City Light) has done good things. They are good partners. I’ve published research papers with their biologists. We’ve done good things, but when it comes to (the issue of blocking off fish habitat), there’s a line in the sand and we can’t get through it.”

Fisher, of Seattle City Light, said historical interviews and information adds value to the conversation.

“Absolutely it’s important to be interviewing the local citizens that are living in the basin and (provide) some history and understanding of what was there,” Fisher said.

City changing position

On Feb. 23, Seattle City Light announced at a public relicensing meeting, held virtually, that they have changed their position and will now study fish passage over all three dams, and that the utility will be the lead investigator. City representatives wrote the commitment in paperwork emailed to the stakeholders. But in writing, they also reiterated their long-held position that their hydropower operation isn’t stopping fish from accessing habitat.

“Fish spawning and rearing habitat upstream of the Project reservoirs are not affected by Project operations,” wrote City Light officials on Feb. 23.

Fisher, the senior aquatics ecologist for the utility, said they are also relying on more recent research. That includes a 2019 genetic study of bull trout in the Skagit River by a US Fish and Wildlife conservation geneticist and scientists from Seattle City Light. The authors found distinct genetic differences between the trout above and below the dams.

“Upper Skagit and Lower Skagit populations (of bull trout) are highly divergent and reproductively isolated from each other,” the authors wrote. “Historical velocity barriers in the Skagit Gorge likely prevented fish passage long before the dams existed.”

In public filings to the FERC, scientists from the tribes, state and federal regulators were highly critical of the genetics study.

“..the artificial delineation of an “upper” and “lower” Skagit, as has been presented by (the city), is contrary to the current state of the science,” National Park Service scientists wrote.

“Samples collected from (bull trout adults) do not show the full genetic or movement pattern, is only a partial data set, and is not the entire picture,” US Fish and Wildlife scientists wrote.

“Poor sampling techniques and bias…has misled the conclusions. It makes it impossible, therefore, to use the data in the manner cited,” wrote scientists from the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe.

“(The genetics) work is laden with inadequacies and prevent any realistic conclusions,” wrote scientists from the Washington State Dept. of Fish and Wildlife.

City Light’s top biologist said it’s not uncommon for scientists to interpret data differently.

“Yes, scientists can disagree, and they disagree all the time,” Fisher said.

“Game-Changer”

Biologists from the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe and the National Park Service said a pivotal change in their understanding of the migration barriers as represented by Seattle City Light came in 2016 and again in 2018 and 2019, when they observed fish where the utility’s science said the fish shouldn’t be.

“It was huge. It was a complete and utter game-changer,” said Shannahan of the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe. “When we saw the fish, it was an awakening to say: ‘Why are we believing what a hydropower facility is telling us about fish passage?’”

The sighting of anadromous fish occurred in the Gorge Bypass, which is normally de-watered by Seattle City Light.

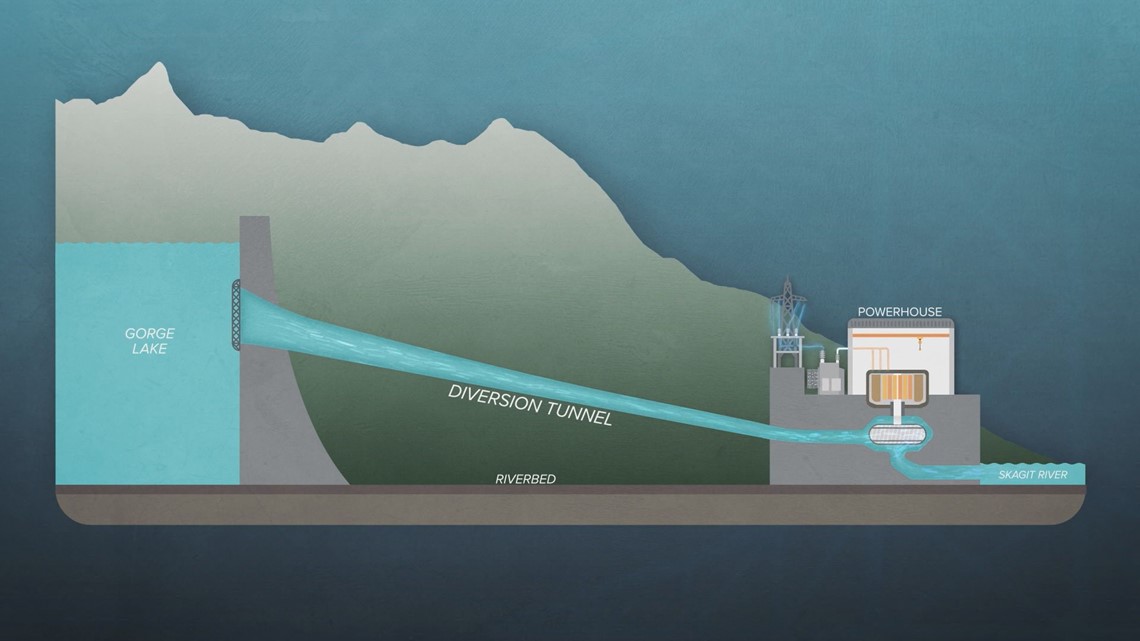

This is a location where City Light’s science concludes the landscape is so rough, fish can’t navigate through the habitat anyway, making it harmless to allow a 2.5-mile stretch of the riverbed to remain dry. Instead of spilling water over the Gorge Dam, the utility diverts the river by blasting it through a power tunnel in a mountain above the Skagit. It’s a man-made tunnel, 11,000 yards long, that provides more force and electricity as the water hits the turbines in the Gorge powerhouse below.

But on occasion, the utility does spill water into the dry riverbed below the dam for maintenance reasons or when there’s an inordinate amount of rain. Since 2016, there have been four instances where scientists have observed fish in the Gorge Bypass when water has been allowed into the area.

In 2019, Shannahan recorded cell phone video of a chinook salmon spawning in an area where Seattle City Light usually doesn’t allow water to be.

In 2016, government biologists snorkeling in the bypass region observed a steelhead swimming above the location described by City Light in federal filings as the most challenging barrier of all to anadromous fish.

“That facilitated a lot of conversation about what is science and what is folklore. Yes, it was a big day,” Shannahan said.

All parties involved in the relicensing agree that many factors contribute to salmon disappearing on the Skagit River, including ocean conditions, climate change, development, and predators. Government and tribal agencies said they are asking for Seattle to do its part by investing in additional mitigation efforts to help offset the impacts of their dams.

“We’re not trying to blame them for everything. That wouldn’t make sense. But we’re just asking them to come to the table to identify their own impacts and help us fix it,” Shannahan said.

“I feel like (Seattle) is a place where we value science and we want our value to apply the latest science. I think that’s a value that the utility holds (as well). They just need to act on it. I think they’re getting close to that and we just need to continue to work together and push that forward,” said aquatic ecologist Tom O’Keefe.