SEATTLE — A small, rural Indian tribe based in Sedro-Woolley accuses the city of Seattle of degrading its culture, identity, and federally-protected treaty rights.

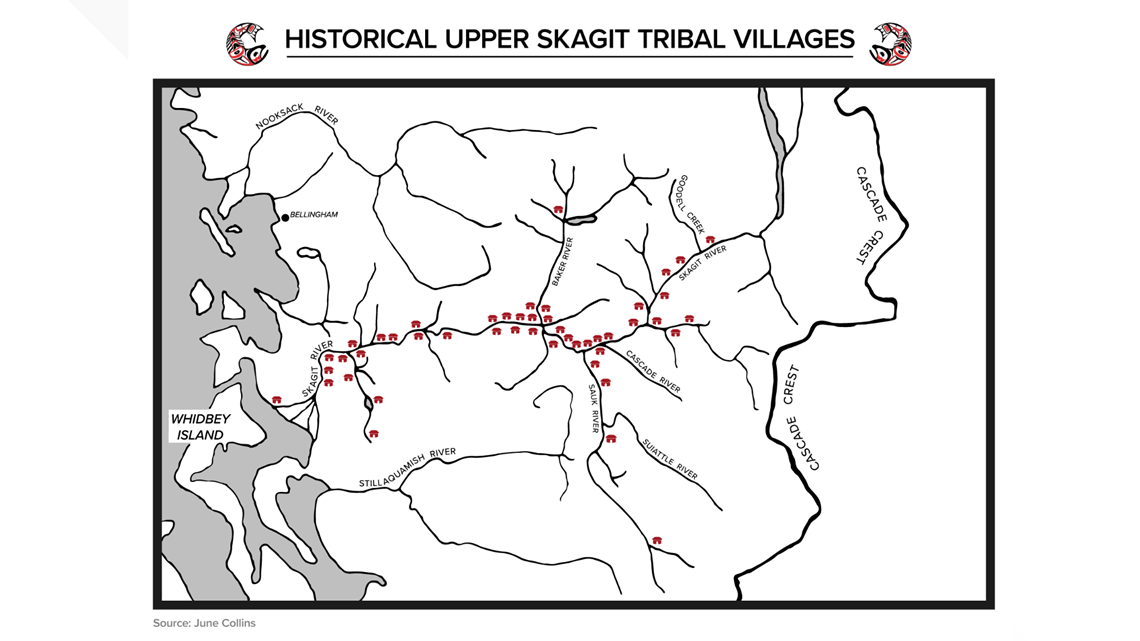

The Upper Skagit Indian Tribe, according to historians, has inhabited the Skagit Valley along the Skagit River for 10,000 years. Members say 100 years ago, their way of life on the Skagit was disrupted. That’s when, without consulting the tribe, Seattle’s publicly-owned utility, Seattle City Light, built three dams in the middle of the Skagit River for the generation of electricity.

The project provides approximately 20-percent of the electricity for Seattle residents and businesses.

Lack of coordination about the city’s operations on Upper Skagit ancestral lands created cost-effective hydropower for the citizens of Seattle. But it also created painful consequences for the tribe:

- Seattle City Light built its company-town of Newhalem on Upper Skagit ancestral burial grounds. That’s where their sacred village of Daʷáylib was located.

- During construction, the city disturbed important cultural artifacts affiliated with the tribe that are remain in the custody of City Light. Utility leadership says they intend to return the items as soon as possible.

- The public utility’s dams created three reservoirs that damaged and continue to block access to important cultural and spiritual sites that now sit underwater.

- The city diverts water out of a three-mile stretch of the Skagit that is considered the most sacred portion of the river to the tribe. The Upper Skagit calls that dewatered section their “Spirit Valley.”

- The dams block nearly 40% of the river to salmon habitat, according to tribal, government and non-profit scientists from around the region. Salmon are sliding toward extinction on the Skagit, the only river that’s home to all five species of Puget Sound salmon. Salmon are a key part of the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe’s cultural identity, spirituality, and community connection.

“We have our elders that lived up in those areas and now that we have the bridges, the culverts, the dams, they’re blocking the traditional ways of life. It’s really sad,” said tribal elder Marilyn Scott who sits on the Upper Skagit Indian Tribal Council. “All of those things are impacting our way of life. It is really hard for our people to survive.”

Larry Peterson, age 48, said his family has a proud history of passing down lessons of their fishing culture from generation to generation. As a child, he spent weeks fishing on the Skagit River, learning from uncles, grandparents, and cousins. With salmon in serious decline, he worries his children have lost out on those irreplaceable moments.

“We are a river tribe. I always tell (my kids), ‘We are tied to this river by blood. Your ancestors have had a part of this river since the beginning of time,’” Peterson said. “That’s what’s being taken away from my children. The important times in an adolescent’s life that they get to spend with their elders (on the river). It’s really heartbreaking, you know.”

Fishing for salmon on the Skagit River isn’t just a family tradition for the tribe. It’s a federally-protected treaty right that dates back to 1855 when U.S. representatives and Puget Sound Indian chiefs signed the Treaty of Point Elliott, in what is now the town of Mukilteo. The chiefs agreed to cede their ancestral lands to the federal government, peacefully, in exchange for one important right: the right to fish in their customary ways and places.

“The right of taking fish at usual and accustomed grounds and stations is further secured to said Indians,” treaty authors wrote.

Scholars of the Treaty of Point Elliott said retaining fishing rights was the line in the sand for the Indian chiefs.

“That promise (of fishing rights) was carefully considered. The United States considered that it was worth it to get all that tribal land,” said Prof. Charles Wilkinson of the University of Colorado. Wilkinson is considered one of the foremost authorities on Indian law, history, and policy.

“In the U.S. Constitution, it provides that the laws and treaties of the U.S. should be the supreme law of the land," Wilkinson said. "So we end up with that promise being that their way of life would be continued. This was central to the tribe’s existence. Salmon is, no question, one of the most prominent ways of life, food and religion.”

With salmon in decline, the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe rarely gets to exercise their treaty rights. Two salmonid species, Chinook and steelhead, are on the endangered species list. Runs of chum, pink and coho are declining in abundance as well on the Skagit, according to data from the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW).

The Upper Skagit Indian Tribe and the WDFW co-manage the Skagit River and agree to specific times the tribe can fish and how many fish they can take, in an effort to limit impacts to the runs.

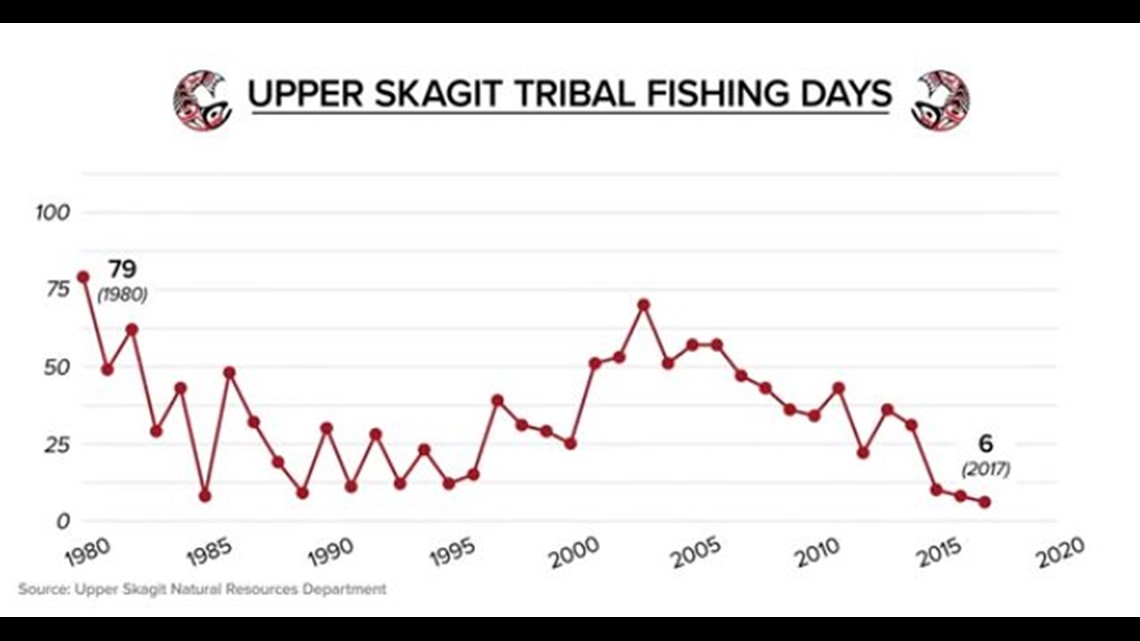

According to data from the Upper Skagit Natural Resources Department, the tribe has gone from a high of fishing 79 days total in 1980 to only six days in all of 2017. In 2018, 2019 and 2020, they fished nine days per year.

“We are a salmon people and salmon mean more than just money, just food. It’s a way of life for us,” Peterson said. “And I can almost say it’s gone.”

Scientists from the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe, the Sauk-Suiattle Tribe, the Swinomish Tribe and government regulatory agencies say Seattle’s dams, which block off approximately 37% of the river, are a big part of the salmon problem. The agencies, including NOAA Fisheries, US Fish and Wildlife, the National Park Service and WDFW wrote in public documents that the dams adversely impact salmon by obstructing miles of habitat for fish to spawn and grow and by altering habitat through impeding the movement of sediment, gravels and woody debris below the dams. The scientists said availability of gravel is important for successful spawning and sediment delivery and transport are essential for improving juvenile rearing habitat.

The only scientists on record saying the dams aren’t part of the dwindling salmon population problem work for Seattle City Light.

City Light’s general manager and CEO Debra Smith said the utility is working hard to be better partners with the tribes and other stakeholders as they seek to have their dams relicensed by the federal government.

“Going forward, our goal is to make sure that all the folks involved in the (relicensing) process with us, but particularly the tribes who do have treaty rights; that they feel listened to,” Smith said. “Treaty rights are super important to us. That is at the heart of the city of Seattle.”

That’s exactly why Janelle Schuyler, age 20, said she wrote to Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan two years ago. She knew the city had a reputation of supporting the rights of indigenous people. In her 2019 letter, she explained to the mayor how seeing the dried-up portion of the river below Gorge Dam, where Seattle City Light operations divert water through a power tunnel, caused her pain.

“I don’t expect you to understand the hurt that I experience knowing the life-giving Skagit has been purposefully dewatered by the city of Seattle,” Schuyler wrote. “I am asking you, Mayor Durkan, for your help after a century of inflicting continual harm on my people and all the creatures relying on a healthy, productive Skagit, for Seattle now to do the right thing … I’m convinced it’s not too late to save the Skagit.”

Schuyler signed off by asking the mayor for an in-person meeting to “discuss options for saving the sacred Skagit.”

“I ask this for my people. I ask this for the salmon. I ask this for the Orca. I ask this for our sacred Skagit,” she wrote.

Schuyler said she never heard back from the mayor.

“As Native Americans, we already deal with a lot of systemic racism and oppression. This just shows that they don’t really care because they are just ignoring our voices. It’s just another thing to add to the list. It makes me feel sad,” Schuyler said.

The mayor’s office did not respond to KING 5’s interview request for this story.

Schuyler has also started a petition on change.org to encourage the city of Seattle to consider the removal of the Gorge Dam. The dam is located on what the tribe considers its “spirit boundary.” As of April 6, 43,760 people had signed the petition.

The Upper Skagit Indian Tribe, through the relicensing process, has officially requested that Seattle City Light access the removal of the Gorge Dam to see if the utility could still meet their hydropower needs by utilizing the other two dams, Diablo and Ross.

Smith said they will not undertake that study.

“(It’s) a really sensitive issue for (the tribe) and we understand that. I understand that,” Smith said. “We’ve been pretty clear from the beginning that our plan has been to operate all three dams and so it doesn’t seem to us like a good use of funds to spend almost a million dollars to study something that we intend to continue to use to generate power.”

Janelle's father, tribal elder and Upper Skagit policy director, Scott Schuyler, said the tribe will continue to fight for the removal assessment for the health of the Skagit River and the honor of their ancestors.

“Our ancestors were robbed of the opportunity to weigh in on the construction of the dams 100 years ago, so now in 2021, we’re speaking for them. Our ancestors are driving the effort to assess the removal of this dam and return the river to its natural state if possible,” Schuyler said. “In the era of social justice (what’s happening on the Skagit), is a huge injustice to the tribe and to our people.”

The Treaty of Point Elliott, promising the retention of fishing rights, was signed by Schuyler’s great, great, great grandfather, Chief Pateus. It was also signed by the most famous Pacific Northwest Indian chief of all: the city’s namesake, Chief Seattle of the Duwamish and Suquamish tribes. His likeness is the face of the city of Seattle and the logo of Seattle City Light.

“There’s a large amount of hypocrisy here that (the city) needs to come to terms with. ‘You can talk the talk, but you are not walking the walk. You need to look in the mirror Seattle,’” Schuyler said.