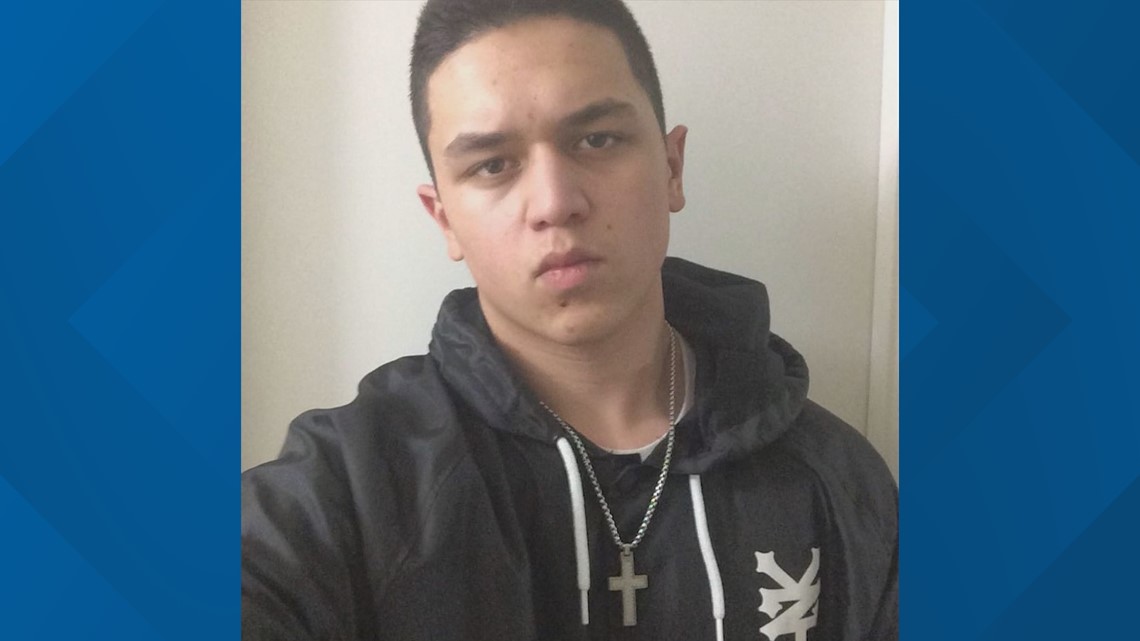

David Cerrone barely had more than the clothes on his back when a Washington state social worker told him that she could not find him a home.

“That first lady that came to pick me up that night was kind of agitated,” Cerrone said of that experience two years ago.

At age 16, the social worker told him that she was going to check him into a hotel until they could find him a more permanent place to stay in the state’s foster care program.

“I went there with my bag of clothes,” said Cerrone.

That more permanent home never materialized, and Cerrone became one of hundreds of foster children each year who spend nights in a hotel room instead of a licensed foster facility.

“It’s kind of a hopeless feeling because it’s like, ‘What is the point of this?’” Cerrone said. “They don’t have me enrolled in school. I’m not able to have friends.”

Data shows the use of hotel/motel rooms to house foster children is on the rise in Washington, even though lawmakers and state agencies have pledged to curb the use of such temporary housing.

The Office of the Family and Children’s Ombuds (OFCO) found 1,514 instances where foster children were placed in hotel rooms in 2019. That’s an increase of nearly 40% in hotel stays over the prior year and by far the highest number of licensed “placement exceptions” that OFCO has recorded since it started tracking the practice five years ago.

“These are traumatic experiences for these children,” said Ombuds Director Patrick Dowd, whose office determined that many of the children housed temporarily have mental health or behavioral problems that require specialized care.

“Some of these children clearly need mental health placement. They’re in a hotel, because the referral for a mental health placement has been accepted, but there’s not a bed date available,” Dowd said, pointing out that the state lacks enough of the necessary resources for those types of children.

Cerrone, who turned 18 in October and aged out of the foster care program, pushed back against the notion that all the children sent to hotel rooms have behavior problems.

“How does a four-year-old have behavioral issues?” Cerrone asked about one small child who lived in the same hotel room with him for several weeks.

“He was just a sweet kid. You could see it eventually took its toll on him, and he got angry real easy about things,” Cerrone said.

Cerrone said that he too went downhill as he passed more than two months spending nights in a Renton hotel room and days cooped up in his social worker’s office building.

“I self-medicated my way through that whole hotel thing,” Cerrone said, admitting that he started drinking every day.

Social workers routinely caught him, but he says he managed to find more booze.

“When I was doing that they were like, ‘Oh, you need to be sober.’ I was like, ‘How am I going to do that when all you want me to do is sit here and do nothing and think about how horrible my life is?’” Cerrone recalled.

Although many children spend only a few nights in a hotel, some stay long term. Cerrone estimated he spent more than 100 nights in a rented room during his two years in foster care.

Cerrone said the whole experience made him feel “pretty lonely.”

“What I feel pretty much I was told was, ‘It’s your fault you have to get sent to these hotels. This is a result of your actions,’ or something like that. It’s my fault I don’t have a place to live?” Cerrone asked.

According to records, each time a child is placed in a hotel room, two social workers are assigned to sit with the child all night long. Sometimes a security guard is added to the mix if a child has behavior problems.

“Why are they putting them up in a hotel? This is pricey,” John Coney, manager of The Grove West Seattle Inn, remembered thinking when a social worker team arrived with a foster child last year at his hotel.

Records show the state paid The Grove $3,326 for one child’s three-week stay. Plus, there are the additional expenses of the round-the-clock staff to watch the child.

After a few weeks the child started fighting with social workers, and the police were called.

“That was kind of the final straw in that one,” said Coney. “They came back and got all his belongings, and that was the last we’ve seen of him.”

Rebuilding a gutted system

“We have got to get ahead of this problem. It is the biggest problem I have, operationally, in child welfare,” said Ross Hunter, secretary of the Department of Children, Youth and Families (DCYF).

DCYF oversees foster care for more than 8,000 children in Washington and is caring for growing numbers of children with mental health problems.

DCYF is trying to rebuild the foster care system that was slashed during the recession more than 10 years ago. Last year, the Legislature provided millions of dollars in additional funding.

“What we really need are placement (resources) at the high end of need, and we’re definitely trying to build that capacity. It’s not a quick change,” said Hunter.

The ombuds report says the answer is not simply adding more foster homes. The state lacks the proper treatment facilities to help stabilize children so they can move in with a foster family.

“These kids need our love and care. We need these placement (resources). These kids need a stable place that can manage their behaviors and bring their behaviors down,” Hunter said.

This year, the Legislature is considering additional money to beef up facilities for “complex” foster cases in which children have mental, behavioral and criminal justice issues.

‘A good place’

Cerrone entered foster care after a falling out with the family that adopted him as a newborn.

Now, he’s re-connected with his biological mother and is living on her barren, three-acre property outside Tucson, Arizona. He resides in a beat-up trailer among the scrap piles that his biological family has collected over the years.

“Some people may think, ‘How can you live that way?’ But I have all the things I need,” said Cerrone.

Those are the things he says Washington’s foster care program did not give him.

“Out there I couldn’t have a job. I didn’t have a family. I didn’t have friends,” said Cerrone. “I feel like I’m in a good place.”