FERRY CO., Wash. — Watch the full three-part series at the bottom of the article.

As the wolf populations continue to grow in the Northwest, so does the conflict with cattle ranchers, especially in Northeastern Washington.

Ron Eslick and his family have been grazing their cattle on land in Ferry County for about 30 years on a combination of state and federal land totaling about 13,000 acres. It is also home to gray wolves.

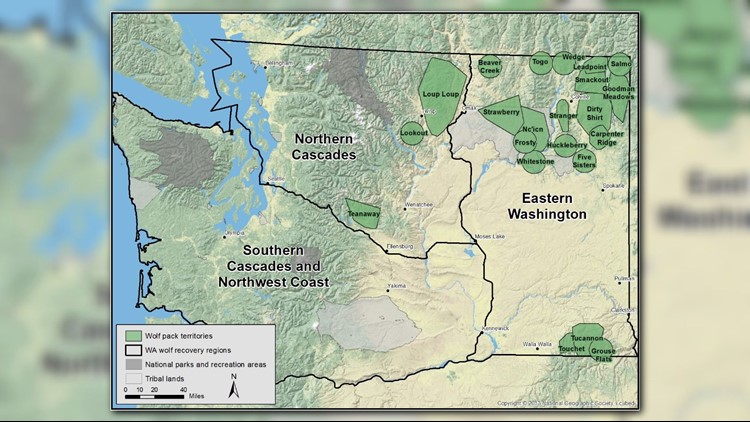

Part of the Eslick family's grazing land is considered the Togo Pack territory. Eslick said over the decades, they've had very few problems, but that all changed in the last few years.

“The day that wolf killed that calf over there, all my cows were right here, in a tight circle,” he said.

Eslick said he has lost three calves just this year to wolf attacks. In May, it was a weeks-old calf killed right along the fence line near his property outside of Kettle Falls.

PHOTOS: Washington ranchers struggle to keep cattle safe in wolf territory

Being just seven miles south of the Canadian border, Eslick is deep in Washington wolf country. There are 22 confirmed packs in the state, about 120 wolves in all. Nearly half of the wolves are in Ferry County, where many ranchers have been grazing cattle for generations.

So why does Eslick choose to let his cattle roam here instead of keeping them in pasture?

“That's more expensive. And without the wolves, you didn't have to worry about it,” he said.

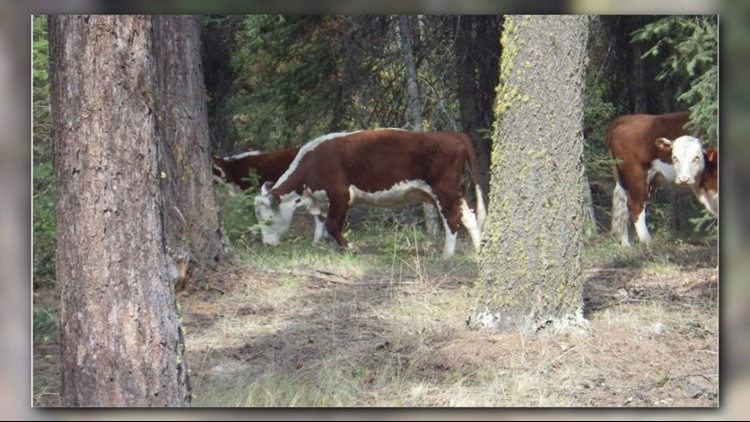

Now, Eslick does worry about it and so do dozens of other livestock producers who typically turn their cattle out in the spring to roam free on huge, densely forested grazing allotments from the U.S. Forest Service. The problem is, in deep woods, cows tend to scatter, making it harder for them to cluster together and protect themselves from wolves.

“They could go all the way down to the river,” Eslick said. “They might even be watching us from here.”

Rancher to critics: 'They don't know the situation'

Eslick let KREM ride along with him as he checked on his herd. Over 13,000 acres, we never found a single cow. Weeks later, he said they all came in but one, another loss he attributes to wolves. KREM ask him how he'd respond to the people who say, "What do you expect these wolves to do? Because we're out in their territory?"

“What I'd say to them is, they don't know the situation. They don't know what's going on here,” he said.

He said, what's going on is the wolves are thriving, while small, family-run cattle operations like his are going extinct. Somewhere in the woods, gray wolves and cows are trying to co-exist. Only one is a protected species, under the active management of Washington's Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Eslick said he’s not necessarily "anti-wolf."

“That's not the case. Because we didn't ask for them to come in. We didn't want them to come in, but what do you do,” he explained. “We've just got to put up with it, don't we? We've got to change our ways, probably.”

Eslick said he’s already changed. Next year, he's planning to sell the majority of his cows. And for the few that he keeps, he'll graze them off of the range, away from wolves. He said, right now, it's the only way in Ferry County to have both.

Environmentalists propose compromise

While it's clear that the current system isn't working for ranchers like Eslick, the other side off the wolf issue is from environmentalists who say, it's not working for the wolves either. That's why some are looking to a grazing allotment. It's still on U.S. Forest Service land, it's the Colville National Forest, but it is much more open. The hope is that both sides will agree that this option works better.

Mike Peterson is the Executive Director of the Lands Council. KREM first met with him a few years ago to talk about the Colville A-Z project, where environmentalists and loggers came together to help prevent wildfires. Now, he's hoping to help save Washington wolves, by working with Washington cattle ranchers.

“You've gotta meet face-to-face. You've gotta build trust. You've got to find common ground,” Peterson said.

For the Lands Council, that common ground might just be restoring the actual ground.

“Ranchers need certainty that they have a place for their cattle in the summer months, and they need forage, and they would like some certainty that they're not getting munched on by wolves. This, restoring meadows, provides a pathway to that certainty,” he explained.

That's where the Lands Council Wildlife Program Director, Chris Bachman, comes in.

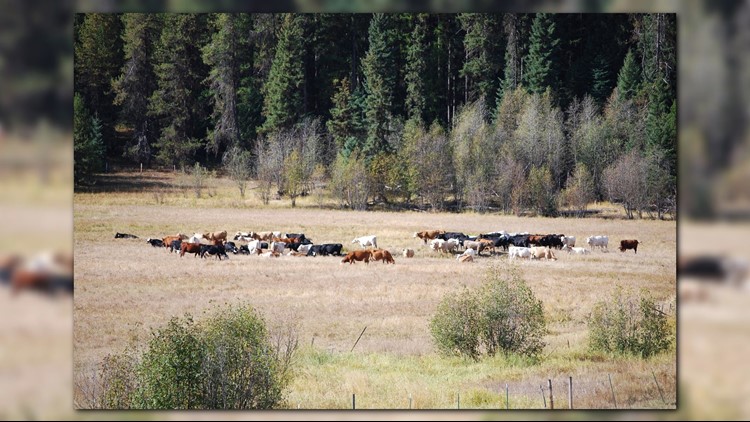

“The Smackout Meadow is a great example of what we could actually have if we restored former meadows,” Bachman said.

Smackout Meadow is right in the heart of the Smackout Wolfpack territory. It's part of a traditional U.S. Forest Service grazing allotment. It offers something most other allotments don't.

“You have a place here where you could have cattle that you can see where they are. You can count them from a distance. If there's any movement in the tree line, or wolves coming in, you can see them, and observe and protect your livestock,” Bachman explained.

It is why the Lands Council is now looking to duplicate meadows like Smackout all across the Colville National Forest. They're poring over old maps and surveys to identify old meadows, that are grown over now, but could be transformed back into better grazing land for cattle, often on many of the same grazing allotments ranchers are already using.

“Could we restore 5,000 acres and the cattle will have enough food right in that one area? I think that's possible,” Bachman said.

When the state first established a wolf recovery plan in 2011, it outlined what to do when wolves attack cattle, including killing problem wolves if there are three attacks within 30 days, or four in 10 months.

Both Peterson and Bachman said the state's own actions are proof that the plan isn't actually fixing the problem. They point just miles to the north, where the entire Profanity Peak wolf pack was taken out in 2016. Today, a new pack has taken its place.

“We have the OPT pack, where again, they removed two wolves, and predations are continuing. Does incrementally removing wolves change pack behavior? At this point, the evidence says no,” Bachman explained. “While I believe wolves have their place on the planet, and their place in the ecosystem, I come out in the middle. To me, it's not all about wolves. It's about a healthy environment, and wolves are a part of that healthy environment.”

Changing minds will not be easy. Both Peterson and Bachman said they already know they won't convince every rancher to get on board, but they're confident they will get some. They believe that's enough to get started on a new way of raising cattle, and protecting wolves, in Ferry County.

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3