Climbing into a volcano is like entering a different planet. There may be blue sky above, but otherwise the surroundings seem alien.

Glacial ice and snow melted by the heat of hydro-thermal or steam vents reveal rock in muted shades of red, brown, black and gray. It can be a noisy place the cacophony of rock and ice fall, joined by the loud hissing of steam jetting out of vents at speeds of one hundred miles per hour or more.

The heat is intense enough to melt ordinary thermometers, and a gas mask is an important safety precaution. Gases include sulfur and arsenic compounds, which crystallize in mounds of sunburst yellow and rust orange around the vents.

In the fall of 1978, I joined scientists on Mount Baker in the North Cascades. That was the volcano considered most likely to erupt. Little did I know that only one-and-a-half years later it would be a different volcano to erupt Mount St. Helens, farther south along the Cascade range.

St. Helens wakes up

About mid-morning in March of 1980, KING-TV received word that there d been a sudden eruption on Mount St. Helens. It wasn t a complete surprise; a U.S. Geological Survey study the year before had fingered this classic cone-shaped volcano as the best candidate for an eruption in the next ten years.

It wasn t because of recent activity, but because of its fairly regular hundred-year cycle of eruptions.

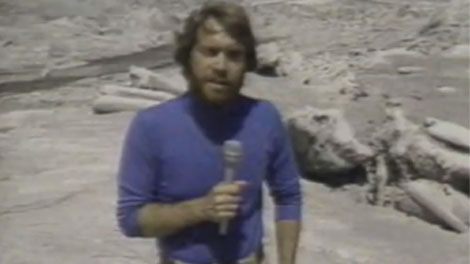

Flying to the volcano in a chartered helicopter, photographer Mark Anderson and I didn t know what to expect. Hearing that the volcano had erupted, the classic image of lava cascading down the flanks and ash billowing out of the summit came to mind.

It was a rare sunny day when we approached St. Helens, and it was quickly obvious that no ash or steam or lava was issuing from the cone. There was a coating of black ash on and near the summit, surrounding a gaping crater.

It turned out that rising magma had triggered a steam eruption within the volcano s internal plumbing, which blew out a small plug of rock. Pieces littered the glacier at the summit.

Camping out

Over the next seven weeks, Mark, engineer Mike Coleman and I spent much of our time camped out on surrounding ridges. We d either offer helicopter rides to scientists or accept them.

I spent free moments studying geology texts to gain a better understanding of what this volcano was doing, and what questions to ask the scientists monitoring this awakening giant.

Sleeping at various times in unheated campers or even tents, we d awake in the middle of the night to downpours, snowstorms or rattling pumice falls from small explosions. After waking one morning to bear tracks just outside, we limited our after-dark tours away from our campsite.

It was the assignment of a lifetime, using our training and skills to tell the stories of both the mountain and the people who either lived there or were attracted by the spectacle. We broadcast daily, meeting a fascinating parade of scientists and characters, several of whom became friends.

One of the former was a geologist named David Johnston, the other a colorful resort owner named Harry Truman.

Harry was a walking, talking seismograph. Visiting him once when the earth began to tremble, he pointed to a swaying Christmas ornament saying, There, that d be about a 5.4...not quite a 5.5, but bigger than a 5.3 . The University of Washington later confirmed his estimate of the earthquake s magnitude-exactly.

David Johnston was one of many dedicated scientists attempting to decipher the volcano s stirrings. A geo-chemist by training, he d take gas samples from volcanoes. Small variations in the chemistry of those gases could point to important changes in the volcano s behavior. David, like many of his colleagues, had a passion for both their science and the grand but dangerous beauty of volcanoes.

A last-minute schedule swap put Dave on duty the weekend of May 18. It was supposed to be a quiet weekend. That s why our crew from KING finally went home for a few days' rest.

The mountain explodes

The morning of Sunday, May 18, was sunny. At 8:32 a.m., seismograph needles blackened the paper-covered recording drums. The eruption had started.

A local resident called me at home to tell me ash was falling on his house. At first that didn't seem alarming, but moments later, when he reported lightning coming out of the ash cloud, I realized this was the big one. We left Seattle almost immediately.

By the time our crew arrived near the volcano, the whole area was engulfed in brownish-gray ash.

We felt a sense of profound disorientation. Nothing looked the same. There was no green, in fact few trees were left standing. The beautiful clear water of the Toutle River was a raging torrent of thick mud and ash.

As we flew beneath the ash cloud and over the river, we d see railroad flat cars, pieces of bridge, logging trucks, pieces of buildings and huge trees all being driven downriver like toys.

Forced by the ash back to the town of Toutle, we joined other helicopters using the high-school athletic field as a landing site. It was then we saw the stretchers, some bearing people needing minor first aid, others covered from head to foot the first victims of the eruption.

Hitting close to home

Later that evening, I heard that both Harry and David were missing and presumed dead.

David, it turned out, had uttered the famous words Vancouver, Vancouver, this is it! seconds before the big blast blew him off the ridgetop.

That was the loss that affected me the most. We were close in age, shared similar interests and a tendency to live life on the edge.

Some months later, I met his father in the Chicago area to share some experiences. As we parted, he said, I miss David a lot, and part of me wishes I never encouraged his interest in geology and volcanoes. But I couldn t do that. He loved his work and used to say that each day was an adventure, an opportunity to learn something new, to use that knowledge to be a better scientist and to help other people.

I hope as people think about the eruption, the transformation of a wilderness wonderland into a moonscape, they ll think of the many scientists, including David, who worked then and now to do just that.