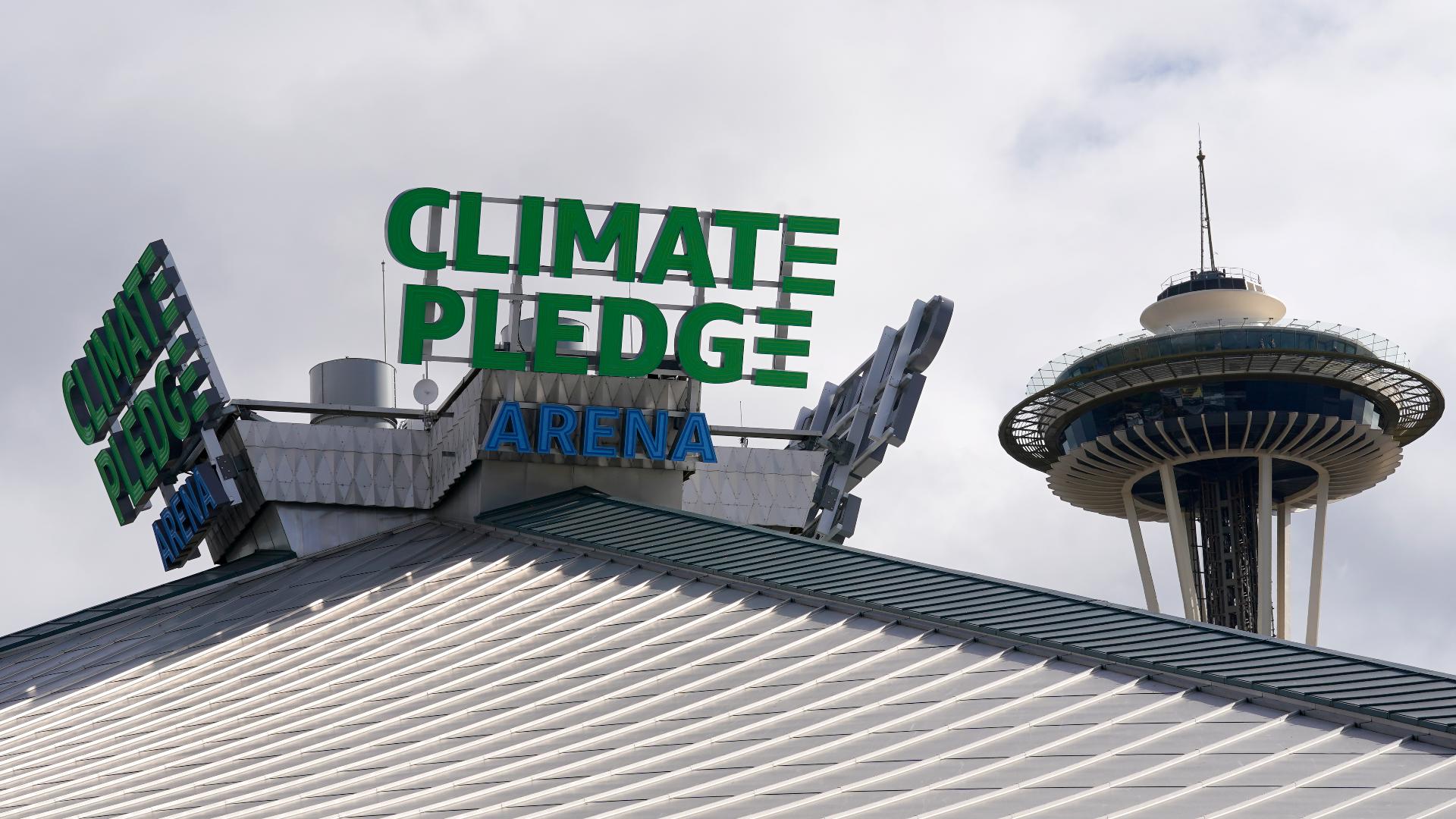

The Seattle City Council put an end to a debate spanning more than a decade by unanimously approving a $700 million makeover of the KeyArena on Monday.

On Tuesday morning in front of the arena, Mayor Jenny Durkan and Oak View Group President Tim Leiweke signed off on the plan.

It is part of what will - likely - be a more than $1.4 billion private investment in the city where an NHL team can call home.

It was expected, and completes a dramatic comeback for the much maligned building.

The effort had been bad mouthed since 2006, and bordered on “white elephant” status after the Sonics left in 2008. More than one developer or entrepreneur looked at the site and moved on.

Back in 2012, the city agreed to a minor touch up in exchange for the construction of a new arena in SODO. After the NBA blew up the deal to move the Sacramento Kings to Seattle, and a new SODO building, there was a quiet and determined movement to replace KeyArena at the current site.

Sally Bagshaw, one of the longest tenured Seattle City Council members, represents the Seattle Center site and would pull what many called a flip-flop. She originally backed the SODO arena project, but always left her ears open for a KeyArena solution. She was quick to latch on to a council-commissioned 2015 report which studied the building’s re-use. It concluded “The Key” could be renovated for the NBA and NHL for $285 million. The report was flawed and turned out to be wildly off base.

Yet, it gave fuel to people like Bagshaw and Seattle Center proponents.

When it came time to approve a street vacation request for the Chris Hansen-led arena project in SODO, Bagshaw showed her savvy political skills. She purposely came in late during a committee vote on the request, casting the lone "no" vote. It allowed for a one-week delay on a final vote, and gave Bagshaw a chance to rally support. In the background, then-Seattle Mayor Ed Murray, who by all accounts was not fully behind the SODO plan, was kicking around the idea of a new proposal centered at the KeyArena site. Bagshaw was known before, and after, as a reliable Murray ally in the council.

Bagshaw, however, showed genuine surprise on May 2, 2016, when four of her colleagues joined her in opposition to the SODO street vacation. Within a week, Murray talked with Hansen and asked about revisiting Seattle Center. Hansen, who had rejected the idea of building there, agreed to allow Murray to give a shot.

The game was on.

Bagshaw found a friend with Councilmember Debora Juarez, another colleague who came from a legal background. The newly elected Juarez chaired the Seattle Center Committee. Both were targeted with hateful, misogynistic emails and calls in the wake of the failed vote, and based on their public comments and appearances, bonded over it all.

Murray’s office was able to solicit bids for a renovated KeyArena from two powerhouses: AEG, which has worked with the city for years, and the Oak View Group, a startup led by the guy who once ran AEG: Tim Leiweke.

Leiweke was looking for a project to kick start his new company, and records show by that summer of 2016 he was itching for a meeting. Bagshaw, and Juarez were immediately impressed with Leiweke’s style and ability to back up his claims. Yet both were skeptical that either group would offer to privately finance a deal.

AEG asked for $200 million in public bondingl. OVG did not, and Leiweke had other tricks up his sleeve.

By the time Leiweke stood next to Murray in June of 2017 at a grand announcement outside KeyArena, he had an NHL partner, too. David Bonderman and Jerry Bruckheimer committed to buying a hockey expansion franchise and put it in the new building. All it took was one Google or Bing search to find that Bonderman was good for the money, and Bruckheimer’s film success added a certain Hollywood flair to it all. They also gave the city a push, and a timeline to finish the deal.

Yet, it risked coming off the rails when Murray ran into trouble later that year.

Leiweke was camped out in a KeyArena suite, ready to celebrate the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding nearby on Sept. 12, when the press conference was abruptly canceled. Murray would resign in disgrace over sexual abuse allegations.

Juarez remained publicly confident the deal would still be completed.

But that meant more negotiations over construction and transportation, and adding a person into the mix who brought charm and local history to the table: Tim’s brother, Tod.

The younger Leiweke left the NFL in March, where he had served as the COO, and No. 2 behind Roger Goodell. Tod Leiweke also had connections from his days as the Seahawks CEO, and knew how to navigate the dicey political scene. He hit the ground running in April, and would later say that he did his fair share of “mitigation” with KeyArena neighbors to avoid conflicts. That meant meetings with KEXP, Pottery Northwest, and the Uptown Alliance, who all had expressed their concerns with the impact of putting another sports complex in the already congested part of the city.

There were some city hall insiders who expected a formal challenge earlier this month to the environmental review, potentially derailing the entire project for several months. But at 5:01 p.m., on Sept. 13, the City Hearing Examiner closed, past the deadline, and without a peep. The following day, a council committee approved the final transaction documents on the mega deal by a vote of 7-0.

“In many ways, today’s full council vote is the closing chapter of a story fourteen years in the making,” Juarez said in a statement, “I am so proud of this moment and what it represents, including our history with both the Sonics and our future with the World Champion Seattle Storm, a proposal which could ultimately lead to over a billion dollars in private investment in Seattle Center. We have achieved a feat rarely seen in the construction of sports stadiums - a public-private partnership where the taxpaying public doesn’t pay for arena construction. I am proud to have played my part in the creation of a world-class asset for our city.”

“While the city has gone through many twists and turns to get to this moment, our patience and determination has led us to a project that is best for the city,” added Council President Bruce Harrell in a statement.

There are skeptics who argue the project is not fully privately financed, given the parking revenues OVG stands to gain, and the fact it will also get the full proceeds from any naming rights. OVG also won’t be paying property tax. The three line items mean potentially millions long term for OVG, that the city will not receive. But Marshall Foster, who has been a City of Seattle lead negotiator, argues the deal will allow the city to receive revenue equal to what it currently makes now, if not more, over the course of the 39-year-deal.

That is likely contingent on the NHL awarding an expansion franchise to the Seattle Hockey Partners later this year. The Leiwekes, along with Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan, will make their pitch to the NHL’s executive committee, made up of league owners, next week in New York City. The group will also tell the owners about its plans to build a team headquarters and practice facility. If everything comes to fruition, the amount of up front money spent in the first two years by the group may be unlike anything this city has ever seen.

Bonderman, a minority owner of the NBA’s Boston Celtics, has also not ruled out spending more to bring the Sonics back. His group is also pitching in millions more for transportation, YouthCare, and affordable housing.

The last event, a Golden State Warriors and Sacramento Kings NBA exhibition game, is a near sellout and scheduled for Oct. 5. It will be a game dripping with nostalgia and storylines, featuring former Sonic Kevin Durant squaring off against the ‘team-that-almost-moved-here’. Depending on the NHL’s guidance, OVG could begin construction a few weeks after that. However, the group has already suggested it could begin KeyArena demolition in December. The city has a mandate that demolition will not begin until an NHL team is awarded to Seattle, although there is a chance that could also be waived. OVG has maintained, no matter what happens this fall, it can open the New Arena at Seattle Center, which would include the historic roof, in October of 2020.

That would be nearly 15 years after Howard Schultz started complaining about KeyArena, and the city was prepared to let it whither away.

If the building was a team, it was the equivalent of being down 10 points in the final minute, with three starters fouled out, and hitting a three pointer at the buzzer to win.

It took six mayors and administrations,to figure it out.

It is, in Seattle’s recent civic history, quite the comeback.