Cap on funding leaves kids with learning disabilities in limbo

It's the state's constitutional duty to provide and pay for an education all kids no matter who they are. That includes the more than 150,000 school-aged kids living with learning disabilities in Washington. But because of an underfunded state special education system, many students with special needs are getting left behind.

Taylor Mirfendereski | KING

Editor's Note: If you are viewing this story on the KING 5 app, click this link.

A Chair In The Class

REDMOND, Wash. — Lindsay Legg changes 6-year-old Noah Lopez-Legg's diaper and immediately sets a timer to begin the countdown.

"Five minutes. We're getting ready to go," she shouts over the repetitive sound of Disney movie trailers, as she grabs her son's shoes and the backpack he loves that’s adorned with a smiley face.

Never looking up from his iPad, Noah paces back and forth through an empty, unfurnished room in their new Redmond apartment. He runs into a wall, unfazed by the impact.

"Three minutes. Then, time for school."

But Noah's not really going to school. That's just what Legg tells him. Routine is essential for her non-verbal autistic child, and the 36-year-old mother is doing all that she can to restore the months of stability Noah lost while she fought, unsuccessfully, for him to have a chair in an Index, Washington classroom.

Noah should — and has the right under state and federal law — to be in kindergarten right now with a free education tailored to his special needs. Instead, he fell victim to an underfunded and outdated state special education system that has ultimately put Noah’s educational future in limbo. It forced Legg to uproot their lives to a new city and pay hundreds of dollars a month for a private therapy program because there wasn’t a spot for Noah in school.

Officials at Index, a tiny school district in rural Snohomish County, told the family that the district was too small to serve Noah, who has unique behavioral challenges such as biting and running away because of his severe autism. He would require a one-on-one aide to help him get through the day and complete most basic tasks, like going to the bathroom.

"It was just like, 'We can't help you. We can't help properly serve him,’ and then no backup plan,” said Legg, who was told the neighboring school districts couldn’t meet Noah’s needs either. "It was like pulling teeth."

Parents like her aren’t supposed to have to plead and fight for their child to be educated.

It’s the law.

Top Official: We Are Breaking The Law

Congress requires public schools in the United States to provide specialized educational services to all children with a disability recognized under the Individuals with Disability Act (IDEA). It’s the state's constitutional duty to provide and pay for every student to have an education no matter who they are. That includes Noah and the more than 150,000 other Washington school-aged kids living with learning disabilities, like dyslexia, ADHD, Down syndrome and autism.

Yet, Index — where Noah was supposed to get an education — is one of more than 100 Washington school districts caught up in a special education funding problem known as “the cap.”

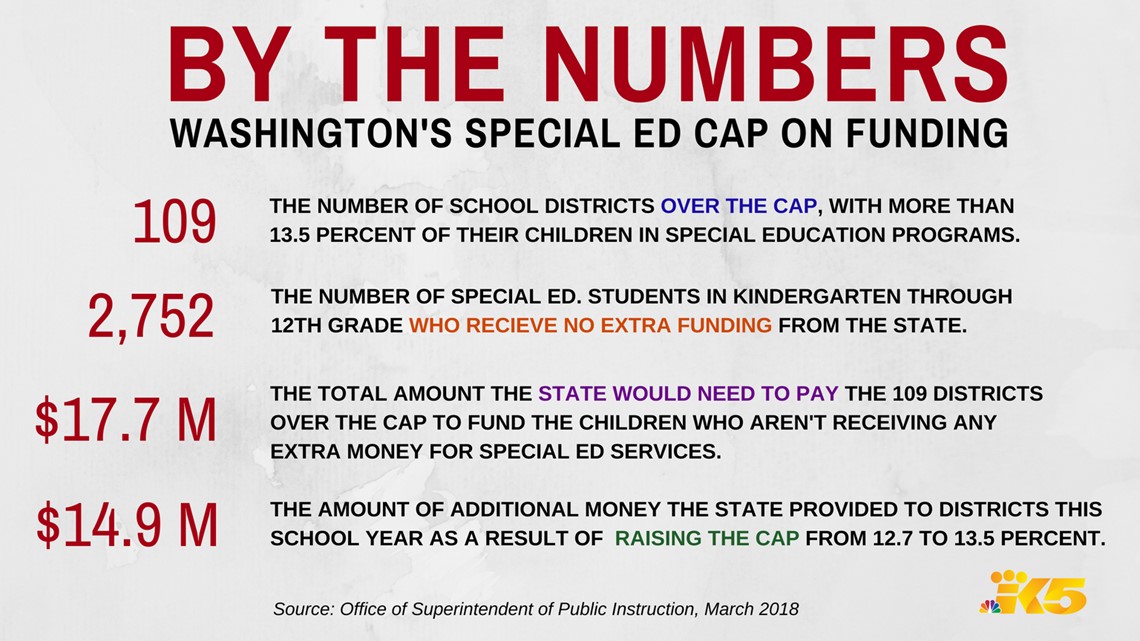

In 1995, the Washington legislature put a lid on the number of disabled kids the state will fund in any given district. Today, it means Washington will only shell out money to support the special education students who make up to 13.5 percent of a district’s total population — even though 109 school districts, including Index, report having more enrolled.

"It shouldn't matter if we are the only one or if there are 20 people like us," Legg said. "Shouldn't we be able to go to school just like the other kids that go to school? Like how can you put a number on that?"

Unlike some states, Washington doesn’t fund the actual cost of special education services. It doesn’t provide different amounts of money to students who have disabilities that are less or more expensive to accommodate. Instead, the state supplements school districts’ budgets by using a complex formula that generates, on average, about $7,000 more per special education student each school year to help cover their excess needs.

A KING 5 investigation into the state’s special ed funding model reveals that more than 2,700 students with disabilities are not receiving an additional penny from the state because of the cap on special ed. It means school districts that serve those students are collectively on the hook for $17.7 million from that funding gap alone. That’s according to an analysis of March 2018 finance records from the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction.

“I’d rather have a (special education) system that says, ‘These students are entitled to it. Districts will serve them effectively. And then districts will get reimbursed for special education services for students with disabilities,” said Chris Reykdal, superintendent of OSPI.

Reykdal, the state’s top education official, admits that Washington is breaking federal law by placing a cap on how many special needs students it will pay for. The state is in violation, he says, because the students have a federal right to be fully and appropriately served.

“There’s absolutely inconsistency between our state budget and federal disability laws,” Reykdal said. “I think (the cap is) fundamentally inconsistent with federal law.”

Elected in 2016, Reykdal has used his short tenure at OSPI, to speak out about the fact that the legislature has failed to provide adequate financial support for the students who need the most specialized help. But state budget writers have historically greeted local school officials on the front lines with a competing message: tough luck.

“It’s a very deliberate and conscious choice to underfund special education for financial reasons,” said Kathy George, a Seattle-based attorney and a special education funding expert. "There’s a willingness by the legislature to let this inequity continue.”

No matter how rich or poor a public school is, the district must still offer and fulfill individualized education programs for every child who is eligible for one. The legally-binding documents, called IEPs, are intended to help kids with disabilities reach general educational goals more easily than they otherwise would. But in reality, some school districts struggle to execute the programs.

“It’s incredibly stressful. You have to comply with the laws, and then trying to find the resources to do that,” said Rebekah Angus, superintendent of Onion Creek, a small rural school district in Stevens County that is over the cap. “The whole idea of having an individualized education plan is to bring the student performing academically up to grade level. But if you don’t have the resources to do that, then you're not fulfilling (the IEP)."

Interviews with dozens of special education experts, including parents, attorneys, school employees, public officials and finance experts, revealed that the cap has unintended consequences on the success of the state’s special needs children. They say the cap:

- Forces school administrators to take resources away from general education budgets in order to stay compliant with federal law.

- Leads school officials to delay, reduce and deny eligible children access to special education services because their district won’t get enough state funding.

- And plays a role in shaping the state’s poor special education outcomes — from low graduation rates to high dropout rates and achievement gaps.

“(The students) are falling behind, and the only way they catch up in those districts that are underfunded is if they have families with the resources to fight,” said George, the attorney and special education funding expert. "We know that's the minority of families, and it's very unfair.”

INTERACTIVE: Is your school district over the cap?

How Did We Get Here?

It’s not uncommon for states to adopt a funding system that seeks to limit the amount of money they spend on special ed.

At least eight states, including Alabama, Alaska and California, don’t consider the actual number of students with disabilities in their districts. Instead, they use historical census data for all funding considerations. In Oregon, districts that have more than 11 percent of students on IEPs receive a reduced amount of money for every student over that percentage.

But Washington is the only state with a funding model that provides no supplemental money to pay for students above a cap, according to EdBuild, a nonprofit school funding research group that has analyzed funding models in all 50 states.

School districts have the option to apply for additional state money on a case-by-case basis through a “safety net" process, but that pool of money is not big enough to meet the demand, a KING 5 analysis of last year’s safety net awards revealed. In turn, many school districts rely on taxpayer dollars to cover their special education costs. Washington school districts reported to OSPI that they collectively spent nearly $165 million in local levy funds on special education during the 2015-2016 school year.

It was a 1995 study that shaped the landscape for Washington’s current special education funding system. Prior to that year, Washington funded special ed based on the number of learning-disabled students enrolled in school districts. It provided different amounts of money for each of the 14 disability categories.

But policymakers suspected school districts were gaming the system by over-identifying special education students since more dollars were attached to each of them. The study echoed their fears, and it led the state to put a 12.7 percent lid on the number of students it would fund with extra special ed money in any district.

“It’s callous. It’s paranoia. It’s ridiculous to think that school districts and parents want to game the system and put their child in a special education setting when their child does not have learning disabilities,” said state Rep. Gerry Pollet, a Seattle Democrat who has been an advocate for special education in the legislature and one of the biggest critics of the cap. "I have never encountered any parent who sought out the diagnosis for their child."

The legislature bumped up the 12.7 percent cap to 13.5 percent at the start of the 2017-2018 school year. It’s a change, championed by Pollet, that forced the state to provide school districts an additional $14.9 million for excess special ed costs. But it took 22 years of pleading to get this small increase at all.

Many blame OSPI’s previous long-time special education director Doug Gill for shaping a culture that caused the state's kids with special needs to lag behind. In an April 2017 interview with KING 5 — just two months before he retired— Gill stated that the 12.7 percent cap was sufficient. He said the cap is essential to keep school districts from getting a "blank check” and to keep parents from taking advantage of the system to get more resources for their children.

"If you went in today and said 'We're just going to take the lid off of special education and it could be whatever percentage you decided it is, I think that would create another funding crisis for both districts and the states," Gill said last year.

"I think it will attract kids whose districts, parents, others believe, ‘Gee they need services. I’d rather refer them to special education services whether I think they need it or not,'" he added.

It's important to understand that even if the cap were lifted tomorrow, special education in the state would still be underfunded by millions of dollars.

Many public schools below the cap also struggle to accommodate student needs because they report a major shortfall in special education funds. The Everett School District, which has 11.9 percent of its K-12 students enrolled in special ed, reported a $9.9 million shortfall this school year.

This all links back to the fact that the state’s complex special ed funding formula doesn’t consider what it actually costs to serve students based on their specific needs. The state allocates the same amount of money per student whether the child needs speech therapy twice a week, or a full-time aide to handle extreme behaviors or medical needs.

You can't just peanut butter the money around and say every kid's going to be taking care of," Reykdal said. "Some need more than others. Some need less than others."

It's why he proposed this year to add $130 million to the state budget for special education in order to mostly eliminate the need for districts to spend local dollars.

The legislature coughed up $21.8 million.

'All The Surrounding Districts Are Full Up'

Before Lindsay Legg rented a place in Redmond, she moved to Index last summer in search of a fresh start.

It was a blow for the single mother and full-time nurse to be priced out of her Kirkland apartment — especially since Noah was making great progress at his Lake Washington School District preschool. But it was also a blessing, she thought, because it was a chance for the two to finally have their own place in a community Legg could afford.

"This is my dream. I'd never bought my own home. We were so excited, and I was so ready to move out there," she said.

She found the perfect home above the Skyokomish River — an idyllic place for Noah's unique sensory needs. She would no longer have to worry about Noah disturbing neighbors at 3 a.m. with his loud and unpredictable outbursts. And she could put up a fence and special locks to keep him away from harm.

But before she even put an offer on the house, Legg's first call went to the Index School District. Could they educate her autistic child?

"I was told 'Yes, we'll figure this out. We'll get him schooled. It shouldn't be a big deal," she said.

She sent the district Noah's IEP so the special education teacher and superintendent could familiarize themselves with his unique needs. Then in August 2017, Legg packed up and headed 43 miles north to start their new life.

But after she’d closed on the house, district officials admitted in e-mails that it wasn't going to be so easy to support Noah in a full-day kindergarten program after all. They would have to contract with neighboring districts to give Noah an education. They cited their own transportation constraints, “toileting issues” and “limited areas for time out.” But by late August, they still didn't have a plan. They even suggested to Legg that she send Noah back to the Lake Washington School District.

"It looks like all the other surrounding districts are full up," wrote Arlis Clarke, the Index special education teacher at the time, in an Aug. 22 e-mail to Legg. "I do not want you to think we are not working on this."

As Legg went back and forth with the school district for months to come up with a solution, Noah sat at home with no place to learn. That went on until November.

Fed up and out of options, Lindsay decided to enroll Noah in the closest specialized therapy center to their Index home – 42 miles away in Kirkland. Instead of a free education for her son, Legg got a second job to pay hundreds of dollars a month for the therapy program and the gas to get him there.

They spent three hours a day traveling to and from the Kirkland therapy center. It's a long time for any child to be stuck in a car — let alone a child with severe autism.

"There were points where we just had to pull over and run around at a park on our way because he couldn't be in the car anymore," Legg said.

By early 2018, Legg said the drive became too much. She decided to sell her home just six months after she bought it in order to move closer to Noah’s therapy center.

"That was really hard to have our own space finally that was really perfect for both of us and then it just vanishes," she said.

Legg hired an attorney to fight for services. On Feb. 28, she settled with the Index School District for $1,760 and 50 total hours of compensatory instruction time for the child. The money, the agreement states, is reimbursement for Noah’s “private service expenditures” last fall.

“That didn’t even cover my lawyer fees,” Legg said, adding that she doesn’t plan use up the compensatory instruction time because it would once again require Noah to be in the car for hours more than he can stand.

Brad Jernberg, superintendent of Index, declined to discuss Noah's case or speak generally about the school's resource constraints, so it's unclear whether the cap played a direct role in their inability to serve him.

We work hard to serve all of our students, regardless of any resource limitations that must be overcome to meet student needs," Jernberg said in an e-mailed statement. "And I know that every school district across the state would likely tell you the same thing."

WATCH: 'He Deserves Everything'

Denying, Delaying, and Reducing Services

The 13.5 percent cap on special education drives some school administrators to encourage special ed teachers and school psychologists to be sparse in providing resources, according to experts.

“There’s no doubt that having a cap means that the pressure flows down through the school building to tell parents, ‘No, you’re not going to get an individualized education plan and services for your child with a disability,” said Rep. Pollet.

Superintendent Reykdal said he doesn't think school districts are explicitly not serving kids, but he admits it's his biggest worry.

"My worry is that (the cap) is causing districts to manage their budget instead of providing the services," he said.

Gill, the state’s former special education director, said in the interview last year that the cap is not causing school districts to deny or delay an education to kids with special needs.

Local superintendents interviewed for this story deny that the cap is having an impact on their ability to follow federal law. But many of them acknowledge that it affects the quality of the education their special needs students receive.

"Our children receive legally the services that they should get. Are they the best services they should get? No," said Rich Dubois, superintendent of the Lake Quinault School District, a small district on the Olympic Peninsula that has 14.4 percent of its kids enrolled in special education services. "But I'm not shortchanging them."

In the Soap Lake School District, a small Eastern Washington district over the cap, superintendent Sunshine Pray agrees that a lack of resources is affecting the school's special needs children and the people who work with them.

"We haven't had to deny any services, but I would say in a small district, the services are not as ample as they could be," she said. "Kids are getting put into general education math classes for algebra and their (IEP) goals are learning to multiply but we don't have another one-on-one (paraeducator) to put in the class.”

Pray said she can't afford to send her paraeducators — the classroom assistants who work one-on-one with students — to trainings that would help them learn more about specific disabilities and how to better serve the individual kids they work with.

"I see some paraeducators who get really frustrated, especially in cases where a student has a disability that's invisible. You don't know what's going on in (his or her) brain," she said. “They are flying blind."

‘You’re Robbing Peter To Pay Paul’

In many school districts over the 13.5 percent cap, superintendents say they are forced to cut into their general education budget in order to meet its legal obligation to educate students with learning disabilities. Experts say that means non-disabled students could get a little less in services so that some students may get services at all.

“On one impact, you have to legally help this student. But on the other impact, you are possibly hindering another student because you’re limiting their (resources),” Dubois said. “You’re robbing Peter to pay Paul.”

In the Columbia School District in Stevens County, superintendent William Wadlington says his district hasn't been able to update its curriculum and technology or complete a roof maintenance project officials have been trying to save up for over the last eight years. Instead, he said, the district put those projects on the back burner to cover their special education costs.

"When we have to put buckets out in our halls so we can collect the water that comes through the roof, that's an issue," he said. "We place kids first, people second and things third. And we are sacrificing a lot of things."

Poor Outcomes

When educators are forced to cut corners due to the underfunded special education system, it's leaving Washington special ed students at the back of the class.

"The data tell us that students with disabilities (are) the single largest group of students contributing to our lack of graduation rate," Reykdal said. "We also know they are absolutely ready and passionate about the work. They can do the work, we just have to support them better."

Only 58 percent of Washington special education students got diplomas in 2016. A 50-state analysis of graduation rates reported to the U.S. Department of Education shows that just 12 states, including Alaska, Georgia and South Carolina, graduated fewer kids with learning disabilities than Washington that year.

Washington has one of the worst track records for being able to keep students with disabilities in school. According to the Department of Education's most recent report to Congress published in 2017, 34 percent of our special ed kids are dropping out. Only two states in the country, Utah and South Carolina, report a higher dropout rate.

“We’ve got some rulemaking we got to do differently here,” Reykdal said. “Our districts have to think about the work differently. They have to train their teachers differently. Our legislature has to step up. We all have a part in this.”

As special education experts and public officials grapple with how to fix a system that is leading so many special education students to prematurely leave school, let us not forget:

There's one 6-year-old boy still hoping to get in.

“We have enough battles that we fight all the time above and beyond what a neuro-typical kiddo might face," said Legg. "Getting a basic education should not be one of them.”

If Your Child Has A Learning Disability

Know your rights. The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction offers guidance for families, which includes a handbook with information about you and your child's rights under state and federal law.

If you have questions about the special education process or difficulties communicating with your school district and need additional help, OSPI has special education parent liaisons available to assist you.

The state also has education ombuds who work with families to answer questions and help resolve concerns. Contact their office online or by phone at 866-297-2597.

About This Series

This story is the first part of "Back Of The Class," a multi-part investigation into the state of special education in Washington. The series exposes the reasons why Washington lags behind much of the country in serving one of our most vulnerable populations: students with learning disabilities.

Contact The Reporters

Susannah Frame is the Chief Investigative Reporter at KING 5. Her stories have exposed many wrongs, leading to changes in public policy, congressional investigations, federal indictments and new state laws. Follow her on Twitter @SFrameK5 and like her on Facebook to keep up with her reporting. For story tips or questions, e-mail her at sframe@king5.com.

Taylor Mirfendereski is a multimedia journalist, who focuses on in-depth reports and investigations for KING 5's digital platforms. Follow her on Twitter @TaylorMirf and like her on Facebook to keep up with her reporting. For story tips or questions, e-mail her at tmirfendereski@king5.com.