OLYMPIA, Wash. — The composting of human remains has turned into a growing business in Washington state. The state in 2019 became the first state to allow an alternate method to traditional burial or cremation procedures.

Four companies in Washington are licensed to turn remains into soil: Earth, Herland Forest Natural Burial Cemetery, Recompose, and Return Home.

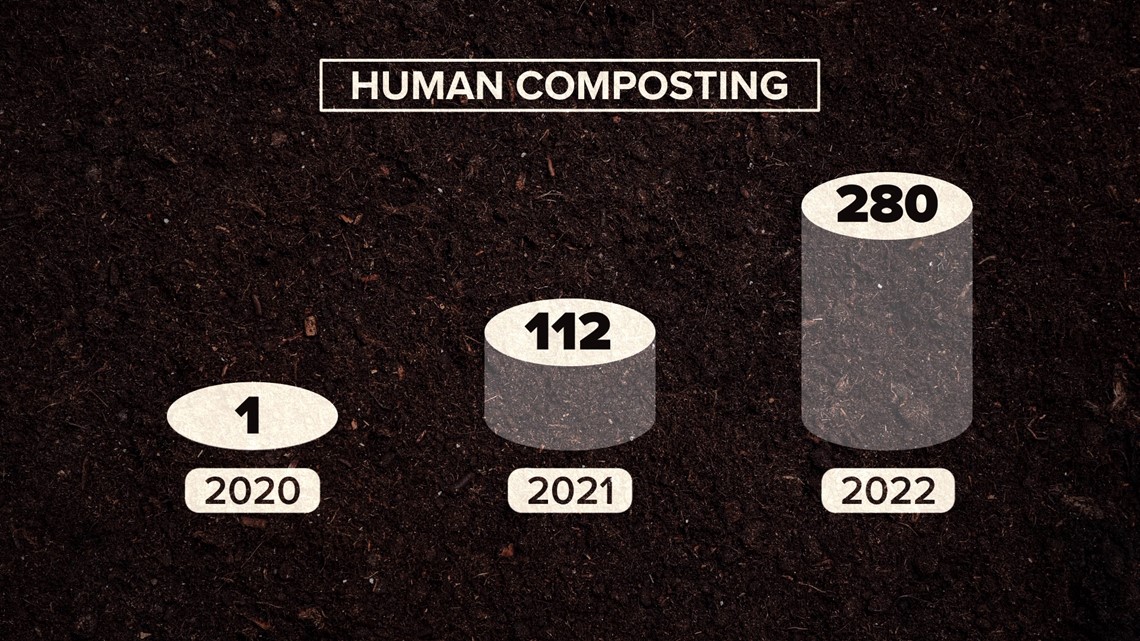

According to the state’s Department of Licensing (DOL), after one person chose the option in 2020, 112 were composted in 2021, and 280 opted for the procedure in 2022. Figures for 2023 have not been tallied yet, said a DOL spokesperson.

Six other states followed Washington’s lead and now allow the procedure.

Earth’s CEO Tom Harries said his company turns remains into soil in approximately 30 to 45 days.

He said the body is washed, wrapped in a plant-based shroud, and placed on a bed of mulch, woodchips, and wildflowers. The mixture is enclosed in what the company calls a vessel, which slowly rotates.

”This is completely natural. No insects, we get asked that sometimes, certainly no chemicals. This is pure nature, optimized,” said Harries.

The typical body generates “a couple of wheelbarrows” worth of soil, said Harries. Loved ones have the option of taking some, or all of the soil. Whatever is not taken is placed on forested property owned by Earth on the Olympic Peninsula.

Harries said the company is looking to expand because of growing demand. He said they sell the procedure in advance for customers who want to be composted when they pass away.

”You can have this gentle natural process, that’s net carbon neutral, that transforms you into soil,” said Harries, “For reforestation and whatever personal memorialization you would wish for.”

Sarah Lewontin chose to have her remains turned into soil after her death.

The Seattle mother said she likes the idea of her death not creating a carbon footprint.

”The remains then can be used to fertilize the kind of plants that keep us from disappearing as human beings from the earth, even as we’re disappearing as individuals,” said Lewontin.

She hopes her family will use her remains in the garden of their Seattle home.