TACOMA, Wash. — The state is expected to wrap its case by Wednesday at the earliest and next Monday at the latest in the trial for the death of Manuel Ellis.

The trial, which initially appeared to be taking longer than expected, could be wrapped up by early to mid-December.

Prosecutors said with a shuffle of witnesses that occurred last week, they will no longer call other officers who responded to the scene on the night that Ellis died, including Officer Timothy Rankine’s partner, Masyih Ford.

Ellis, a 33-year-old Black man, died in Tacoma police custody on the night of March 3, 2020, after a confrontation with officers.

Officers Matthew Collins and Christopher Burbank are charged with second-degree murder and first-degree manslaughter in Ellis’ death. Rankine is charged with first-degree manslaughter.

Were Tacoma officers justified in initiating interaction with Manuel Ellis? It depends who you believe

A police use of force expert said whether Tacoma officers’ initial interaction with Ellis was justified depends on which version of events jury members ultimately believe.

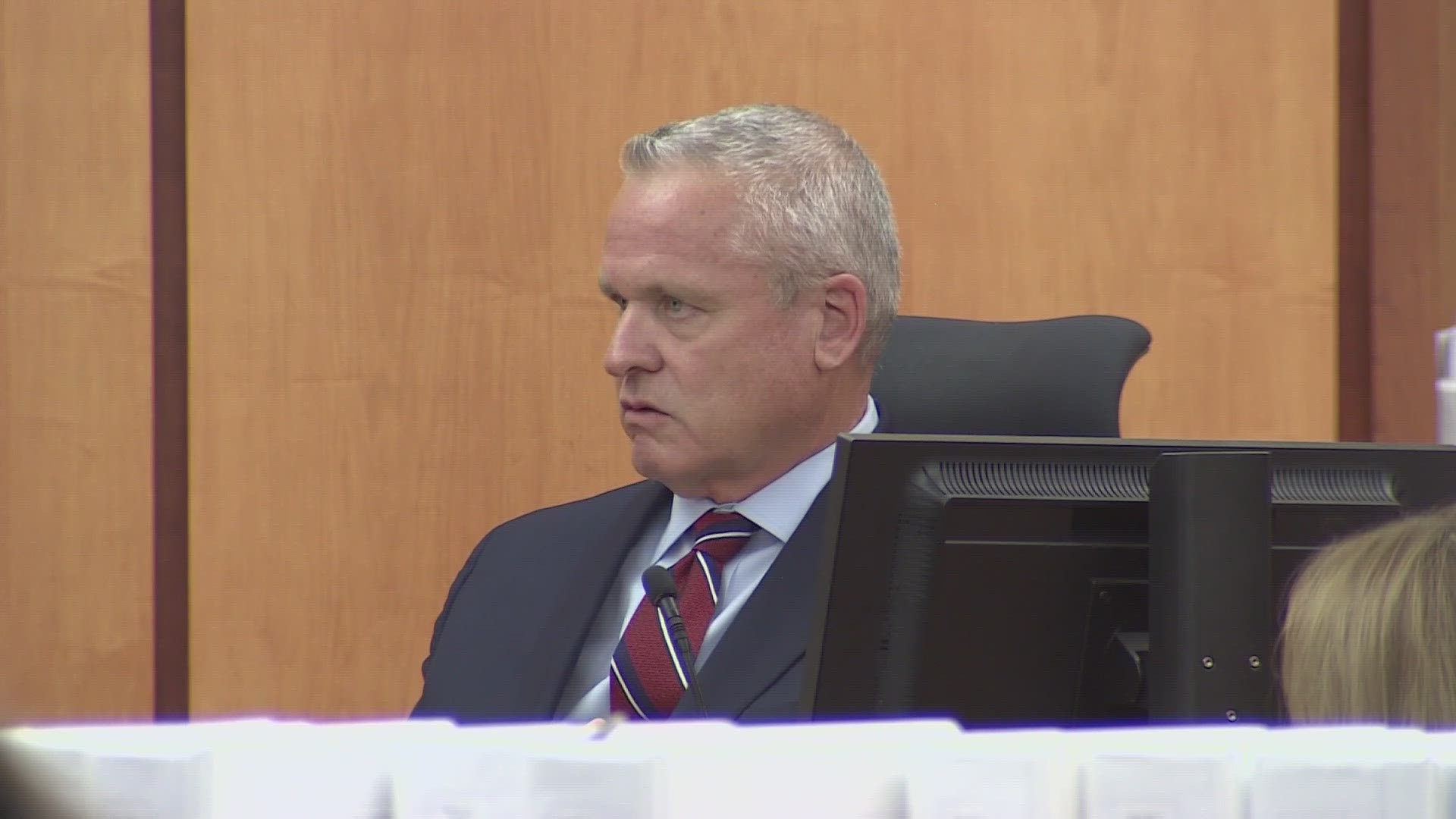

John Ryan appeared on the witness stand Monday. He provides training for police officers nationwide, does audits of law enforcement agencies and has helped write policy in over 20 states. He also serves as an expert witness in civil and criminal litigation and was a police officer for over 20 years.

State prosecutors in the trial over Ellis’ death asked Ryan about police training standards relating to appropriate use of force, initiating interactions with the public and placing suspects in a prone position.

Burbank and Collins said the night that Ellis died, they pulled up to Ainsworth Avenue South and South 96th Street and spotted Ellis in the intersection, attempting to get into a car that was making a left turn. Collins said he called Ellis over to the patrol car to ask what he was doing, then told him to go sit on the sidewalk. Officers said Ellis then went over to the passenger side of the patrol car and began beating on the window.

“They certainly would have had reasonable suspicion to stop, and they would have had probable cause to arrest,” Ryan said.

However, that version of events is contradicted by multiple bystanders to the incident.

Eyewitnesses recalled seeing Ellis walking down the street when it appeared he was beckoned to a patrol car idling at the light. One eyewitness, Sara McDowell, recalled that Ellis was knocked over by the passenger door of the patrol car as he attempted to walk away. Then both officers exited the car and started beating Ellis, McDowell said.

By this account, officers would not have even had the grounds to call Ellis over, Ryan said.

Ryan agreed with the prosecution that it was not his job to evaluate the credibility of either story.

“That’s up to you,” he said, referring to the jury.

Officers should ‘immediately’ remove suspects from prone restraint position

During direct examination on Monday, prosecutor Lori Nicolavo pursued a line of questioning that suggested officers should have known not to leave Ellis in the prone restraint position – especially not with someone on his back.

“This is something that’s been trained to law enforcement for decades,” Ryan said.

Officers are told that they can put a dangerous suspect in a prone position to “accomplish restraint” but that a suspect should be removed from that position once they’re handcuffed “for the purposes of facilitating breathing.”

In training, officers learn about how someone in a prone position who is handcuffed may not be able to get their lungs to expand all the way. This concern is heightened for someone who is hobbled, particularly if their hands and legs are connected like Ellis’ were.

“It makes the position even worse,” Ryan said.

Multiple medical experts and the former Pierce County medical examiner determined that Ellis’ death was a result of oxygen deprivation caused by police restraints. A pulmonologist testifying for the state said the position that Ellis was in, paired with the weight of an officer on his back, would have limited his ability to expand his ribcage to inhale completely.

Nicolavo then asked about what officers’ responsibilities are regarding the well-being of suspects in their care. Ryan said officers are trained to monitor suspects for signs of distress, any signs of injury, illness or a lack of oxygen.

Ryan noted that someone telling officers “I can’t breathe” should be enough of an indication that a suspect is suffering from a lack of oxygen.

On the night Ellis died, he was heard saying he couldn’t breathe multiple times, which was captured on a nearby home security camera and also heard by Rankine, by his own admission.

At any indication that a suspect is in distress, officers are supposed to get them evaluated by medical professionals immediately, Ryan said.

The state is arguing that all three officers on trial violated their duty of care by not seeking medical attention for Ellis when he told them he was having trouble breathing.

Additionally, Ryan said the way in which Ellis was restrained - in a "hogtied" fashion - is discouraged and, based on witness video, appeared to be excessive.

Use of force

During his testimony in the afternoon of Nov. 6, Ryan said that, collectively, the officers' use of force against Ellis was excessive.

"Force is fluid. When a subject is doing a lot of resistance, you get to meet that resistance with a certain degree of force. As that resistance goes down, then your force has to go down with it. But you take into account everything that happens over the period of time," he said.

Ellis was tased three separate times while he was being restrained. Ryan said that, based on witness videos, he did not see a level of resistance from Ellis that justified the use of Tasers. Ryan said police training discourages multiple deployments of a Taser on someone as it can increase the risk to them.

Additionally, punching Ellis when he was already restrained would not be excessive, according to Ryan.

When it comes to the neck restraint by Collins, Ryan said it was not necessary, especially if Ellis was already in handcuffs, and it put Ellis at unnecessary risk as it can cut off oxygen.

When cross-examination began, the defense pointed out that while officers are trained in best practices, they also have to react to rapidly evolving situations. Ryan said while that's true, it doesn't justify excessive force.

Defense will continue its cross-examination on Tuesday, Nov. 7.

Background on the case

On March 3, 2020, Ellis was walking home when he stopped to speak with Tacoma Police Officers Burbank and Collins, who were in their patrol car, according to probable cause documents.

Witnesses said Ellis turned to walk away, but the officers got out of their car and knocked Ellis to his knees. All witnesses told investigators they did not see Ellis strike the officers.

Other responding officers told investigators that Burbank and Collins reported Ellis was “goin’ after a car” in the intersection and punched the patrol car's windows.

Witness video shows officers repeatedly hitting Ellis. Collins put Ellis into a neck restraint, and Burbank tasered Ellis’ chest, according to prosecutors.

Home security camera footage captured Ellis saying, “Can’t breathe, sir. Can’t breathe."

Rankine, who was the first backup officer to arrive, applied pressure to Ellis' back and held him in place while Ellis was "hogtied" with a hobble, according to documents.

When the fire department arrived, Ellis was “unconscious and unresponsive,” according to documents.

KING 5 will stream gavel-to-gavel coverage of the trial from opening to closing statements. Follow live coverage and watch videos on demand on king5.com, KING 5+ and the KING 5 YouTube channel.