SEATTLE — Twenty years after the Nisqually earthquake hit, Washington is slated to finally have a system designed to warn residents of damaging earthquakes.

If something like the ShakeAlert Earthquake Early Warning System existed on Feb. 28, 2001, residents may have gotten an alert that severe shaking was about to start. But those were advances seismologists could only dream of back in February 2001.

“That would not have been possible 15 or 20 years ago, because we didn’t have the bandwidth and the internet connectivity to do it,” said Bob Norris, a retired seismologist with the U.S. Geological Survey.

When the magnitude 6.8 Nisqually earthquake struck, Norris was arriving at Harbor Island in Seattle to check earthquake instruments. He planned to download data from an accelerometer, which measures the speed of earthquake shaking. Harbor Island was of interest because it’s a manmade island and all fill, which tends to have higher accelerations during an earthquake than other areas.

It was newer technology at the time and one of dozens stationed around the region to measure small frequent earthquakes and separate it out from background noise, like vibrations created by trains.

Just a few minutes before 11 a.m., Norris was pulling up next to the building where the accelerometer was stationed when the earthquake hit.

“As I turned in, the truck started yawing from side to side, and I thought I had run over something,” Norris said.

That was the first wave from the Nisqually earthquake – the P wave or compressional wave, which travels fastest and causes light shaking.

Then 10 seconds later, the much stronger S wave arrived, bringing violent shaking. S waves, or shear waves, shake the ground perpendicular to the direction the wave is moving.

“I was holding onto the steering wheel and actually got a little whiplash out of it, because the shaking was really strong,” Norris said.

After the waves stopped, Norris got out of the truck and heard a wet, gushing sound. A dome of water was boiling out of the ground as the fill soil lost its strength in the earthquake, causing liquefaction.

The accelerometer recorded shaking that continued to reverberate for minutes through Harbor Island even though deep underground, the earthquake at the site of the fault was over.

Now, the technology exists to use the timing of those waves over distance to warn us when to brace for an earthquake.

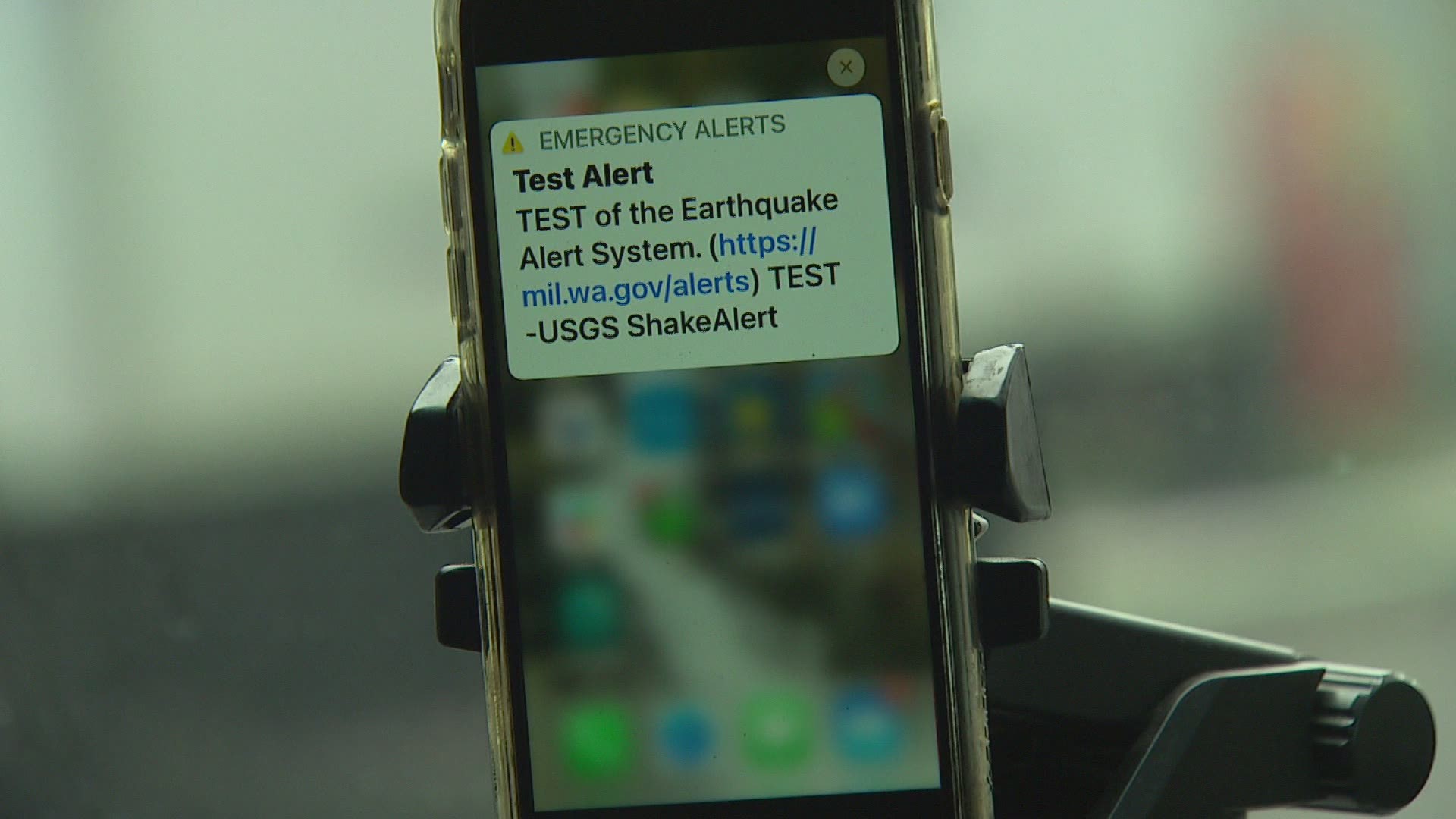

If an earthquake of the same magnitude as Nisqually happened later in 2021, people could get an alert on their cellphones through the ShakeAlert warning system. When sensors pick up seismic waves, that triggers an alert that shaking is expected.

The warning system is expected to be able to deliver alerts to wireless devices starting in May.

This couldn’t have happened 20 years ago, but now with hundreds of seismometers and other sensors hooked up to fast computers, we can act before we get hit.

The warning system aims to give people time to prepare for the earthquake by dropping, covering and holding on. The system can also help businesses, schools and hospitals prepare.

Pacific Northwest-based Varius provides ShakeAlert systems to close valves at water utilities, schools and reservoirs. It also has pending applications in hospitals so the company can warn surgeons to put down a knife or cauterize an open wound, according to Dan Ervin, executive vice president of Varius.

In the aerospace industry, ShakeAlert could put airplanes in a holding pattern so they aren’t landing on fractured runways.