SEATTLE — The rash of tiny, deep earthquakes doesn't predict earthquake risk in Seattle. But this time they are less robust and scientists want to know why.

First discovered by Japanese scientists, these so-called "silent earthquakes" are deep tremors around the earthquake prone Pacific Rim. A little over 20 years ago, we didn't know they existed.

"Every 14 months for 20 years, we've been seeing regular clockwork events," said Harold Tobin, Washington state's seismologist and head of the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network based at the University of Washington.

Tobin said they've noticed an interesting shift in this batch of silent earthquakes. The change this time is that the pattern of deep earthquakes is not as robust as other events which have been watched since the late 1990s.

"We don't know if that's a major change, or [if] the next one will cycle back to the normal pattern," he said.

Tobin specializes in the study of subduction zones, where the crustal plates making up the deep ocean floor are pushed under, or subducted, below the continental plates.

The upper level of those plates closer to the surface are typically locked. One of those locked zones is along the west coast of North America. That locked zone is under extreme pressure, and when that pressure becomes overwhelming a large magnitude nine earthquake is expected someday along the coast of Washington, Oregon, California from Cape Mendocino north and up beyond Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada.

That would trigger a potential tsunami warning for Washington.

RELATED: '14 days isn’t even enough': Survival experts team up to create state-of-the-art earthquake kit

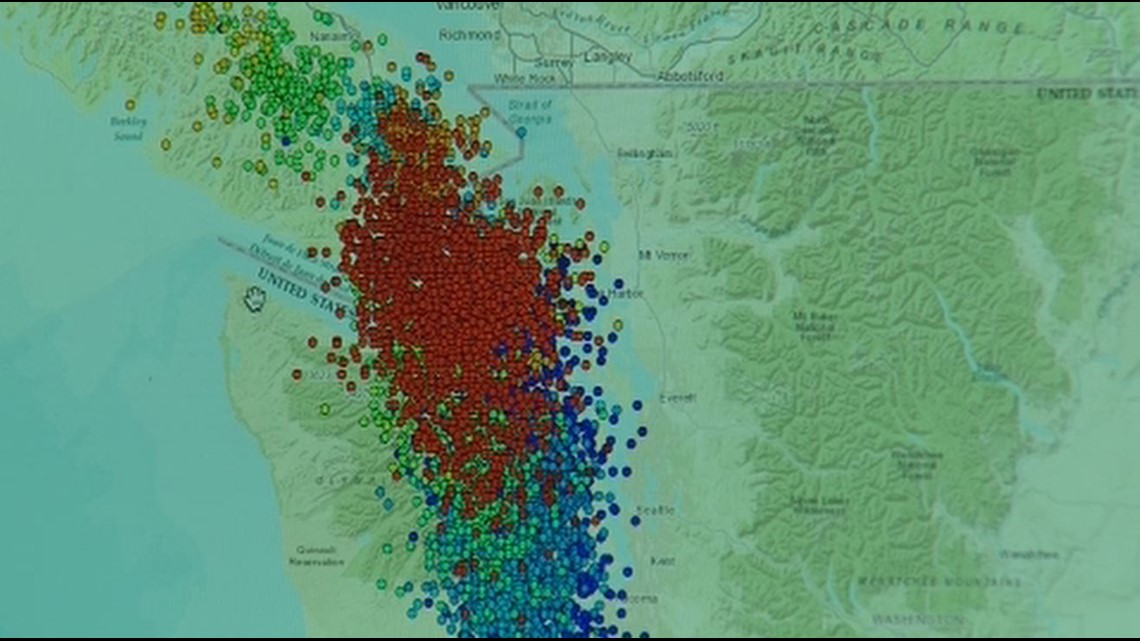

However the locked zone is west of where the colored dots end.

Deep below, some 40 miles underground, the plates are not locked together. As old ocean floor is reheated near the hot mantle of the earth, the plates are believed to slip past each other and stretched like soft plastic resulting in a tiny earthquake nobody can feel.

Tobin and other scientists say that if all the tiny earthquakes were added together they would represent a 6.0-7.0 magnitude earthquake. Since they don't go all at once, and play out over weeks, there is nothing to feel.

"These are micro events. We put a lot of dots on the map, and it happens to look very scary, but nobody feels any of this tremor and it's not a hazard in and of itself in any way," said Tobin.

The same plate that makes for interesting science 40 miles underground, is connected to a system where the upper plate can lead to the world's biggest earthquakes. When those magnitude 8.0-9.0 earthquakes are triggered, massive tsunamis follow. Such was the case in northeastern Japan in Marcy of 2011, when an estimated 16,000 people were killed, mostly by the tsunami waves, Japanese authorities said.

One theory contends that deep tremors could heighten the odds of a major earthquake as the plate's leading edge is pulled deeper into the Earth. That's a theory Tobin doesn't subscribe to.

"I don't get more worried about a subduction zone earthquake during a deep tremor event," Tobin said.

But he does believe there's a lot to learn. Scientists have only known about the quakes for 20 years, yet we know subduction and the drift of continental plates has gone on for billions of years.

In that context, the last two decades are a mere peek into a much, much longer time horizon.

"This is a deviation from that pattern," said Tobin. "I can't draw any conclusion from that until we learn more."