Washington school district violates special education laws for a decade

A three-month KING 5 investigation uncovered a pattern of wrongdoing in the Mabton School District, including violation of federal and state special education laws.

Editor's Note: If you are viewing this story on a mobile device, click this link to see the full story with photos and video.

Pattern Of Violations

MABTON, Wash. — All it takes is three short grunts or a hand motion for Lorena Ramirez to know exactly what her 17-year-old son, Anthony Moran, wants.

If he's hungry, Anthony grunts to get his mom's attention, and then he moves his tongue around like he's tasting something.

If he wants to watch a video of trains on YouTube, he looks at Ramirez's hand until she pulls out her phone.

And if he wants to feed the dogs or the chickens in their Yakima County backyard, he stands by the window and grunts three times until Ramirez says "yes."

Despite Anthony's severe autism, the mother and her soon-to-be high school senior have no trouble understanding each other. But the Mabton School District Anthony attends denied him the specialized educational services he needs to learn to communicate with anyone else.

"Sometimes when he wants something (and people don't understand what he's expressing), I can see how he gets frustrated," Ramirez said. "He must be thinking, 'My family knows what I'm saying. Why don't they know?'"

Since Ramirez enrolled him in the Eastern Washington district 12 years ago, Anthony has made nominal academic progress. He still needs help with all aspects of daily living. His education records compare his life skills to that of a 4-year-old. His communication skills, according to the same records, match that of a 3-year-old.

He can't count. He can't write. He can't say his own name.

"I sent my baby to these people, and they didn't help him. They didn't help him progress," Ramirez said. "They didn't help him do anything, and they lied to me about it."

A three-month KING 5 investigation into Anthony's case uncovered a pattern of wrongdoing in the Mabton School District. Officials there violated state and federal special education laws, including the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) — the law that guarantees all students with disabilities receive the specialized services they need to reach their full potential in school. Special education experts say the district's failures will likely cost Anthony a meaningful future due to his lack of progress.

"He's not learning the things he needs to learn in order to be able to function within the community as an adult," said Wendy Marlowe, a Seattle-based neuropsychologist who evaluates students with disabilities. "So every year that he fails to receive a meaningful benefit from services, he falls further behind and becomes less competent in comparison with his peers than he was the year before. You wind up having a student at the age of 18 or 21 who doesn't have the basic prerequisites to function in society."

The findings, based on an analysis of more than 700 hundred pages of Mabton education records and legal documents, revealed:

- For at least a decade, the district did not allow Anthony and an unknown number of other students with disabilities to attend a full six-hour school day.

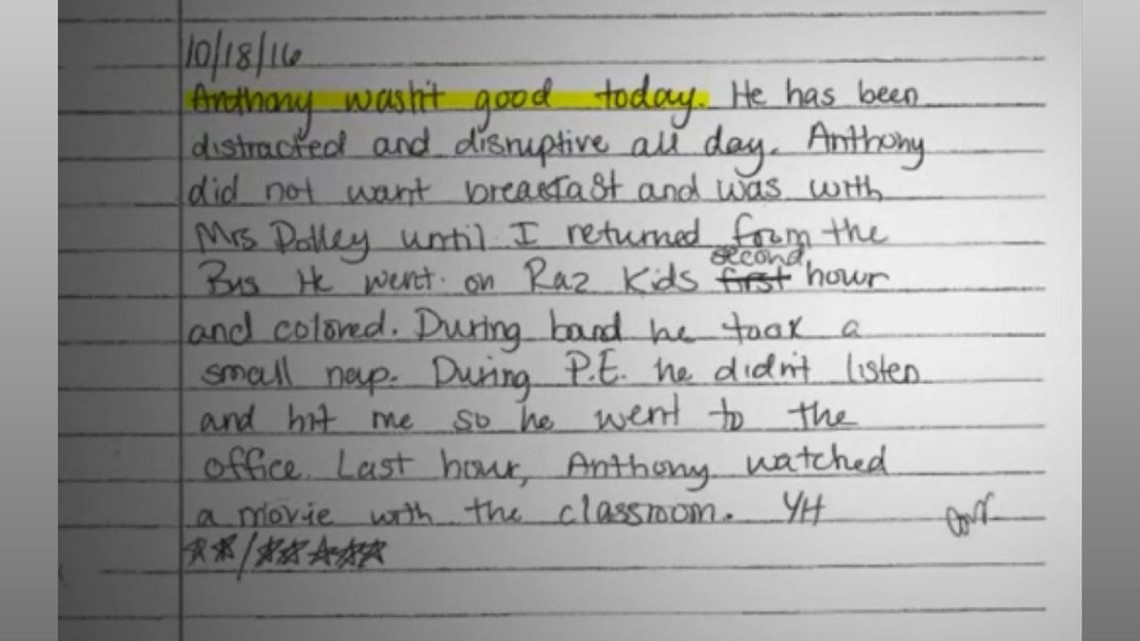

- In classes where other kids would get academic instruction, special education staff occupied Anthony with non-academic tasks — like sleeping.

- Mabton officials denied him access to assistive technology to facilitate his communication skills, despite recommendations in legally binding education plans.

- Anthony was denied access to licensed specialists who could provide services that experts said he needed, including speech therapy, occupational therapy and behavioral support.

- School officials punished Anthony dozens of times in at least one school year for behavioral issues directly related to his disability.

- District officials misled Anthony's parents about a variety of issues, including his academic progress and the services he received.

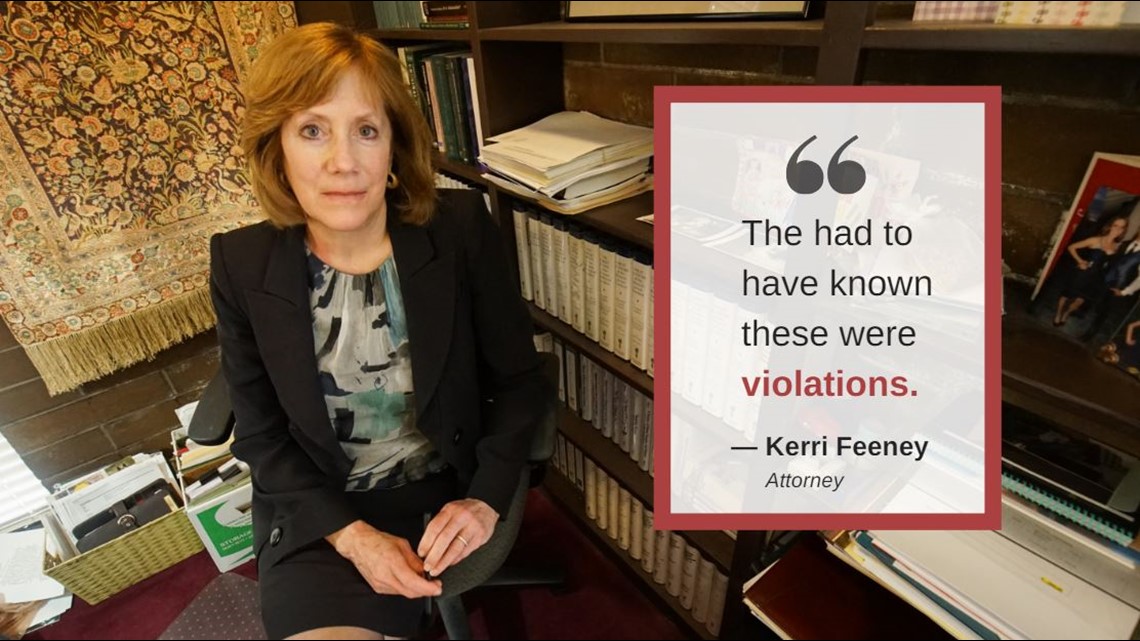

"It's the most egregious (school district) that I've come across because of the number of issues and the length of time that the issues have gone on," said Kerri Feeney, a Richland-based attorney who represented Anthony's mother when she filed both state and federal complaints against the school district in 2017. "They had to have known these were violations."

Mabton school administrators, who have since retired or left the district for other jobs, admitted to most of the violations in legal documents related to Ramirez's state and federal complaints.

But the six current and former school officials repeatedly contacted for this story either declined interviews, dodged questions or did not respond to requests for comment.

Shortened School Day

For at least 10 years, the Mabton School District denied Anthony and other special ed students who have high needs the opportunity to spend a full day at school.

The district bused Anthony and his classmates home from school an hour earlier than the rest of student body, according to legal documents and interviews with parents in the district.

That's a violation of state law because Washington schools are required to provide students with an average of 1,027 hours of instruction each year.

In Anthony's case, the loss of an hour each school day adds up to about two years of lost instruction time in class throughout his primary and secondary school years.

"How does my son get all that back? You know, like all the hours that he missed of school?" Ramirez asked. "How do you repay him for that? What did he lose out on?"

A detailed examination of Anthony's individualized education plans (IEPs) over six years offer insight into what he missed. The legally mandated documents are designed to help special education students reach their goals. The documents require educators to track a student's progress, but in Anthony's case — he was making little.

For three school years in a row — eighth, ninth and 10th grades — Anthony made no documented progress in life skills, communication or academics. His IEPs listed annual goals like identifying a parent's phone number, using a sponge to wipe a spill from a flat surface and improving his ability to write his name. But those goals —along with 21 others — were repeated word for word in his IEPs over those three school years, indicating that Anthony never reached them.

"I have yet to come across a person who does not make progress. I have not met anyone with autism who does not learn," said Arzu Forough, executive director of the Washington Autism Alliance and Advocacy.

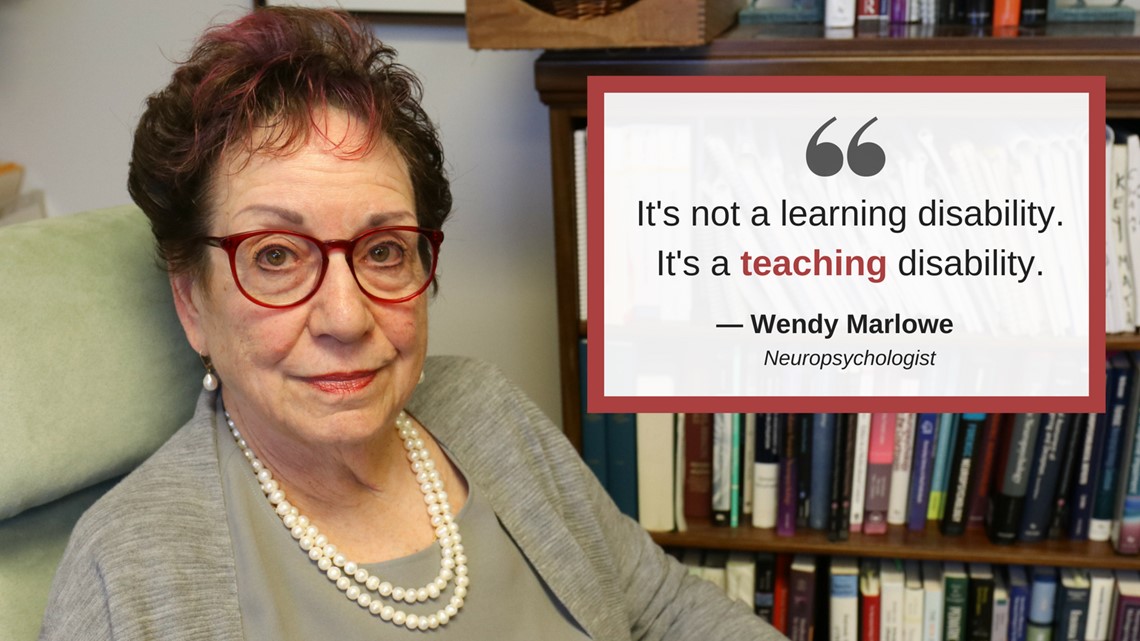

Marlowe, the Seattle-based neuropsychologist, said it's not normal for a special education student's goals to repeat year after year.

"It's outrageous," she said. "They know you're supposed to keep records of progress, and when a student isn't progressing what you're to do is ask yourself, 'Why not? What do I need to do differently to educate this child?' Instead, what happens is they blame the kid, 'Oh, well he can't learn.' It's not a learning disability. It's a teaching disability because everybody can learn."

She said Anthony's shortened school day likely affected his success in class.

"Students with special needs need more time in the classroom — not less," Marlowe said. "Every one of those hours is a learning opportunity....That's what they lose. They lose the opportunity to acquire information -- to acquire strategies."

For years, Anthony's mom didn't bat an eye when her son came home early from school. It had always been that way since she enrolled Anthony in Mabton schools, she said. So Ramirez thought all special education students were bused home early nationwide.

"It happened to all the kids in his classroom. That's why I never noticed, you know, that I could say something about a school schedule," the mother said.

After Ramirez realized in 2017 that her son was missing out on school, her attorney filed a discrimination complaint against the school district with the U.S. Department of Education's Office of Civil Rights. The office found enough merit to take on the case, which led to a resolution agreement with the school district in November 2017. The agency ordered the district to conduct training, review its policies and report back on how many kids this affected and how they could resolve the issue.

"As soon as I filed a complaint about it, all of a sudden (the school district) contacted me and said, 'Oh, hey guess what? Your son is going to be able to attend a full day. You know, we had some busing issues but they have been resolved,'" Ramirez said.

It's not immediately clear how many special education students were bused home early, and why the district denied them a full school day. E-mails to the former Mabton school transportation director, school board president and former special education director were not returned.

Minerva Morales, the former Mabton superintendent who retired this summer, declined repeated interview requests via e-mail in May. She cited student privacy laws and stated that focusing on "any one school district would not be beneficial for that particular school district."

Morales added that it's expensive for schools to provide specialized services to students with disabilities, even though they require the extra help.

"The challenge is that funding earmarked for special education is usually less than needed to meet school legal obligations," she wrote via e-mail on June 1.

That's an issue facing not just Mabton, but school districts across the state. A previous KING 5 investigation found that special education in Washington is underfunded by millions of dollars, leaving students with disabilities in limbo, with inadequate services — or no specialized services at all.

No Communication Support

Anthony's biggest challenge is his inability to communicate outside of his home.

So for four straight years, educators recommended in Anthony's legally binding IEPs that he get access to assistive technology that could help him learn to express his wants and needs.

They talked about the benefit of giving the non-verbal student a specially-programmed iPad that would allow him to communicate with non-family members for the first time.

Ramirez said the district repeatedly came up with excuses — but no iPad.

She said school officials told the family that a speech therapist was working with their son. Yet, there is no proof in Anthony's educational records that a licensed speech-language pathologist supervised or designed his speech therapy — as state law requires — from 2013 to 2018.

"I think that's the biggest letdown. You send a child (to school) who is non-verbal, who is supposed to work on some type of communication (skills), and you tell me he is, but he's not." Ramirez said.

District administrators admitted in a February 2018 legal document that they didn't have a licensed speech pathologist on staff for six months in the 2016-2017 school year. They also admitted they didn't notify Anthony's parents of the situation.

"I feel like they didn't value him at all. They didn't care. If they would have been advocating for him, they would have been providing all the things he needs, and they didn't," Ramirez said. "I feel like they failed me at educating my son."

Anthony's educational records also indicate that he didn't have access to an occupational therapist after 2016. But he still showed signs of needing occupational support. For example, Anthony couldn't hold a pencil.

On top of that, the school district never hired an autism specialist to provide behavioral therapy, despite a documented escalation of behaviors — including biting and slapping para-educators, running away from them and refusing to participate in class.

Special education experts say it's common for students with severe autism to display behavioral issues when they don't have the right support, and it worsens when the student doesn't know how to express their wants, needs and feelings.

Dozens Of Naps

Despite having IEPs that stated specific goals, Anthony did not always receive actual educational instruction.

"It's never OK for a student to be warehoused their entire life," said Forough, the Washington-based autism expert.

A review of Anthony's daily school logs reveals he routinely spent much of his day asleep. Anthony took at least 75 naps in the 2016-2017 school year, according to incidents documented in the logs.

"It's not like I'm sending my son (to school) for you to babysit him. I'm sending him for you to educate him," Ramirez said.

Instead of getting to the bottom of why Anthony became aggressive or consistently fell asleep, district officials punished him for it.

When he wasn't stuck in the library with books he didn't know how to read, Anthony spent a lot of his days in "time out" for the behavioral issues, which are directly related to his severe autism. In the 2016-2017 school year, his aides documented 32 times where he was put in time out or sent to the principal's office.

"It was just kind of like the para (educators) were left with kids and left to figure out what to do with them. Just so (the students with disabilities) don't, you know, bug the teacher or they don't interrupt the class," Ramirez said.

In legal records, district leaders denied that they "repeatedly" removed Anthony from the classroom to a more restrictive environment, like the library or the administrator's office. They stated the "few" occasions of disciplinary action were effective to get Anthony back on task.

"Anyone who didn't have access to effective communication tools must have endured some traumatic experiences not being able to communicate for their basic needs," Forough said. "I think it's going to to take (Anthony) a while to get over that."

'I Am Frustrated'

In 2018, the Mabton School District finally provided Anthony with that specialized iPad to help him learn to communicate in school and in the community.

Anthony recently used the iPad to create a three-word phrase on his own: "I want marble."

It's the first time the 17-year-old has ever communicated a phrase that long.

"Oh my gosh, it's the next best thing to him talking," Ramirez said.

Ramirez has been her son's voice his whole life. It's hard, she said, to fathom all that could be different if Anthony learned a lot sooner to use his own.

"I can't wait to see what this (iPad) is going to do for him, but I'm also kind of sad that we had to wait this long for him to have something like this," she said.

A week after Anthony formulated the phrase about marbles, he hit another milestone.

He used his iPad to express more than a need, or a want. For the first time, he communicated how he felt.

"I am frustrated."

Resources and Support

If Your Child Has A Learning Disability

Know your rights. The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction offers guidance for families, which includes a handbook with information about you and your child's rights under state and federal law.

If you have questions about the special education process or difficulties communicating with your school district and need additional help, OSPI has special education parent liaisons available to assist you.

The state also has education ombuds who work with families to answer questions and help resolve concerns. Contact their office online or by phone at 866-297-2597.

About This Series

This story is the fifth part of "Back Of The Class," a multi-part investigation into the state of special education in Washington. The series exposes the reasons why Washington lags behind much of the country in serving one of our most vulnerable populations: students with learning disabilities.

Part 2: Washington kids with disabilities often denied right to learn in general education classrooms

Contact The Reporters

Susannah Frame is the Chief Investigative Reporter at KING 5. Her stories have exposed many wrongs, leading to changes in public policy, congressional investigations, federal indictments and new state laws. Follow her on Twitter @SFrameK5 and like her on Facebook to keep up with her reporting. For story tips or questions, e-mail her at sframe@king5.com.

Taylor Mirfendereski is a multimedia journalist, who focuses on in-depth reports and investigations for KING 5's digital platforms. Follow her on Twitter @TaylorMirf and like her on Facebook to keep up with her reporting. For story tips or questions, e-mail her at tmirfendereski@king5.com.