Fighting Heroin: Dealers charged with homicide when customers die

In the face of a nationwide heroin crisis, more police agencies are investigating overdose deaths as crimes. But are the dealers responsible for lives?

Editor's Note: If you are using our mobile app, click this link to view the full story.

In disbelief, Martina Moreno snapped a picture of the fresh needle tracks on her daughter's left arm.

By all accounts, Tylar Pryor had never used heroin until that late August night when Bremerton medics responded to the overdose and found her drunk and unresponsive on her bedroom floor.

A doctor told Martina there was no hope her daughter would wake up from the five-day coma. So on Sept. 1 of last year, the mom reluctantly agreed to unhook the only machine keeping the 31-year-old Tylar alive.

"You can't describe the heartbreak, knowing that your daughter is gone. The person laying in the bed is not your daughter," Martina said, in tears. "I shut down. I shut down."

Tylar was just hours away from taking her last breath. Martina hovered over the Harrison Medical Center hospital bed and plucked her daughter's eyebrows. She combed her hair and pulled it up into the same ponytail Tylar fussed over daily.

It was the only comfort the 56-year-old Ephrata woman could find in those fleeting moments of her daughter's life. But after Tylar died, a police officer shared the "satisfying" news that the two people who supplied the heroin -- Nicole Browitt, 25, and Christopher Fletcher, 24 -- were in jail, charged with controlled substance homicide for causing Tylar's death.

"If I had been in a more clear mind, I would have gone back to the house and stood on the corner and watched (the arrest)," Moreno said.

The felony statute that holds drug dealers responsible for overdose deaths is seldom enforced, even though it's been on the books in Washington since 1987. But in the face of a nationwide heroin crisis, more law enforcement agencies are beginning to investigate overdose deaths as crimes, in order to prosecute dealers when the drugs they sell kill their customers.

It's a move that has changed the way some police officers do their jobs. Patrol officers are responding to medical emergencies they once left to paramedics. Special operations detectives are starting immediately on drug investigations that used to go untouched for days and even weeks.

"A couple years ago, overdoses were ruled accidental deaths. The thought was, 'Well, no one overdoses intentionally unless we can find a note that says, 'goodbye cruel world,'” said Detective Sgt. Billy Renfro, who oversees drug overdose investigations at the Bremerton Police Department. "Today, our detectives are getting called to the scene -- sometimes when the victim is still there.”

Bremerton detectives are hopeful drug dealers will think twice when a harsher penalty is on the line, and that grieving family members, like Moreno, can find closure after a difficult loss. It's a shift in attitude that's spanning some parts of the state and much of the country, as public officials at nearly every level search for new ways to quell the opiate problem that continues to get worse.

Opioid overdoses have quadrupled since 1999, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2015, the CDC recorded 1,094 drug overdose deaths in Washington -- up more than 10 percent from 2014.

"If a drug dealer gives another person a controlled substance and that person dies, how do you look at that any different than if that person had a gun and he shot the person?" said Detective Sgt. Brandon Greenhill, who led the Bremerton Police Department's investigation into Pryor's death. "The drug is the weapon, and the drug is what killed the person so why not go after that person who used the weapon to kill?"

Many prosecutors across the country agree, and they've recently used their powers to hold dealers accountable for overdose deaths, bringing charges like involuntary manslaughter, negligent homicide and third-degree murder. In an unconventional move last year, the Lycoming County, Pa. coroner ruled nearly half of the county's drug overdose deaths as homicides instead of accidental.

"I think we're just sweeping the problem under the rug if we call these accidental deaths. How is it an accident when somebody dies from an illegally supplied substance?" Lycoming County coroner Charlies Kiessling said.

But not all public officials agree with Kiessling. Many believe calling an overdose death a homicide is not an ethical or an effective way to curb the nation's opiate problem.

It can be near-impossible to prove a direct link between an overdose victim and a dealer. Even if investigators can make the connection, critics say the cases are often in direct conflict with Good Samaritan laws that provide legal protection for people who assist someone in danger. In some communities, police officers are not criminally investigating overdose deaths because public officials have opted to put more resources toward public health initiatives to combat addiction.

"Frankly, the debate we're having as a community right now is: Is this a public health issue or is this a criminal issue? Are we going to lock people up as a way to sort of manage use among drug users and the drug communities or are we going to try to find some way to treat it as a public health issue with harm-reduction strategies in other things?" said Mark Larson, the chief criminal prosecutor at the King County Prosecutor's Office.

Why Convictions Are Rare

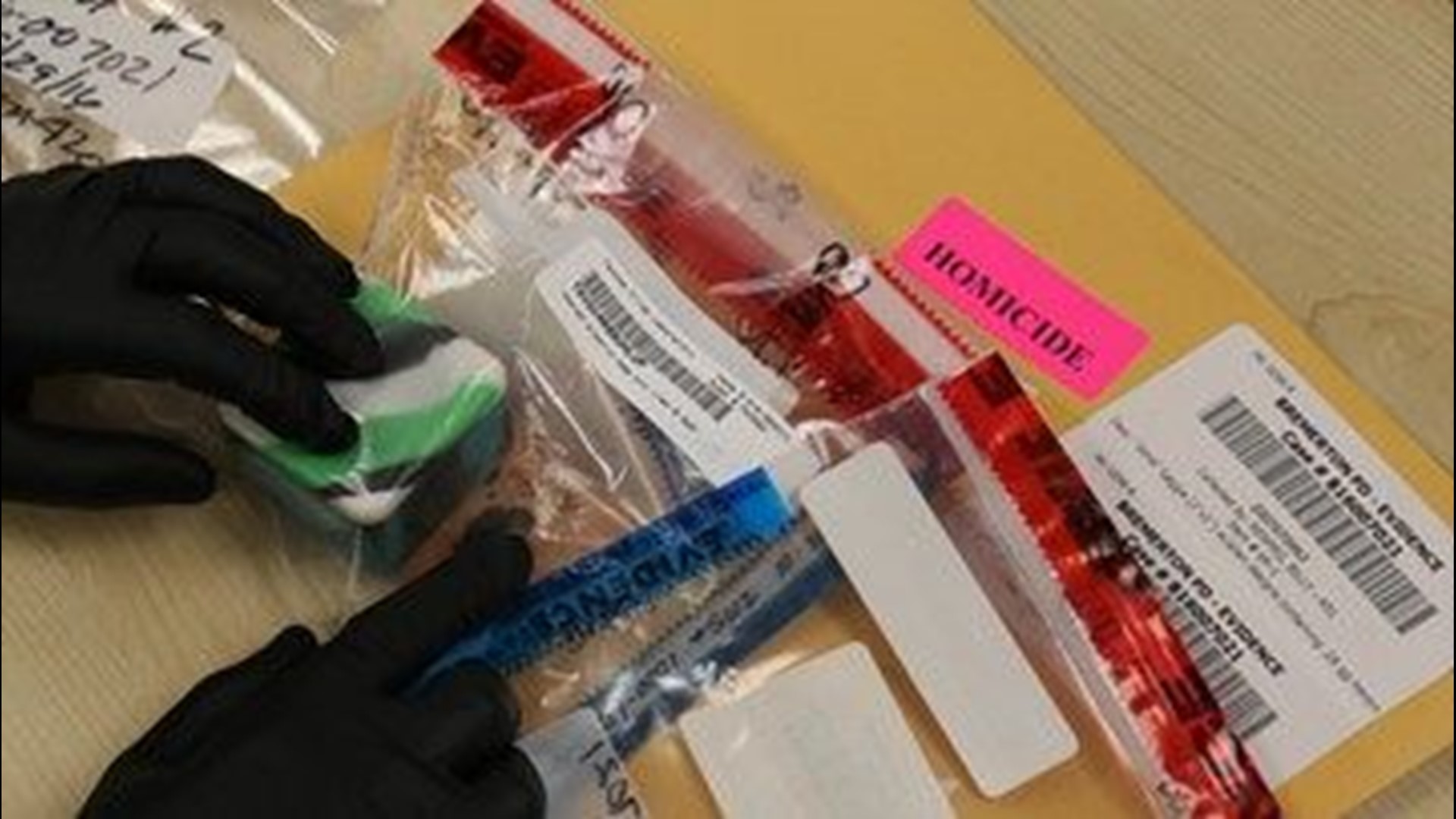

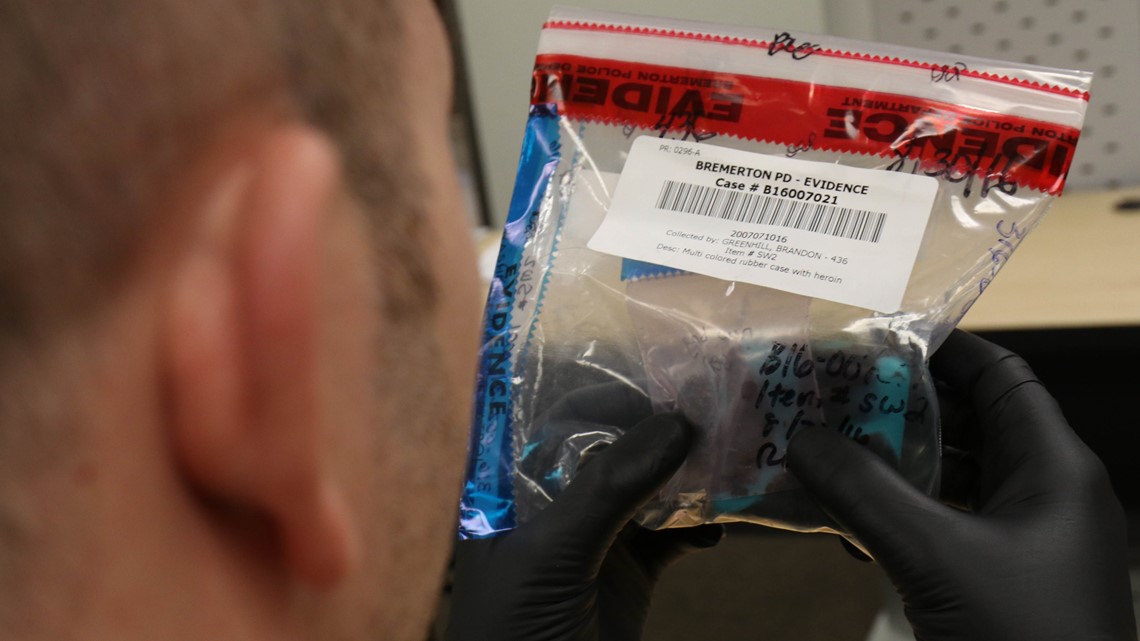

Greenhill, who investigated Pryor's death, has four active drug overdose death investigations on his desk.

The Bremerton detective is trying to find enough evidence to directly link the drugs that killed each victim in those cases with specific dealers. It's the only way the Kitsap County Prosecutor's Office can convict a dealer on a controlled substance homicide charge, which carries a prison sentence of up to 10 years. But making a case can be a lengthy, puzzling road.

Of the three cases Greenhill has already wrapped up for the Bremerton Police Department since he started working on controlled substance homicide investigations full time in March 2016, only one of the four people he arrested and charged with controlled substance homicide received a guilty verdict. Two people had their charges reduced, and one person is still awaiting trial.

"Most users have multiple dealers that they are getting drugs from," said Coreen Schnepf, senior deputy prosecuting attorney at the Kitsap County Prosecutor's Office. "Most of our witnesses are other users and many times uncooperative because they don't want their friends to get in trouble for this type of offense."

Often times, the evidence prosecutors receive from police is not strong enough to convince a jury that a dealer's drugs caused the user to die, according to police and legal experts. And even if they can link the drug dealer with the person who died, the autopsy has to conclude that the victim died from the drugs the dealer sold -- not other factors.

That's one reason why some police leaders said they don't even try to pursue these time-consuming investigations and the reason why many officers haven't been taught to respond to calls involving possible overdose deaths.

"Sometimes it's a lack of witnesses or evidence on the scene, and all you have is a toxicology report to go on. Sometimes, that's not enough to track down the person who supplied the drugs," said Renfro, who oversees Greenhill's investigations. "It's not a violent scene. If you've got a shooting or a stabbing, you have good evidence."

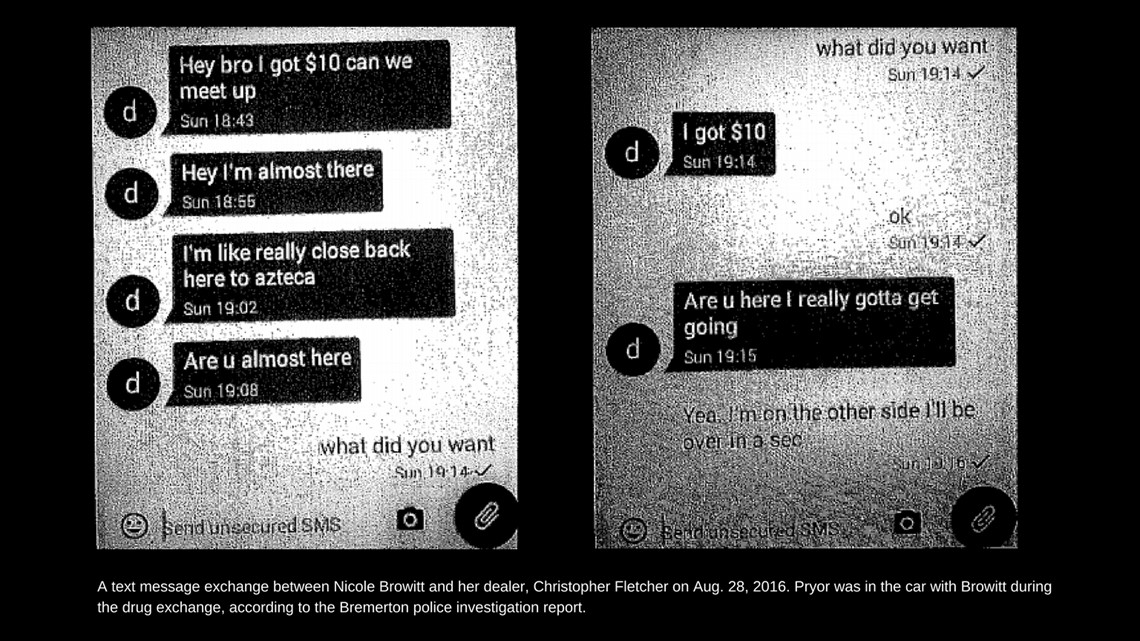

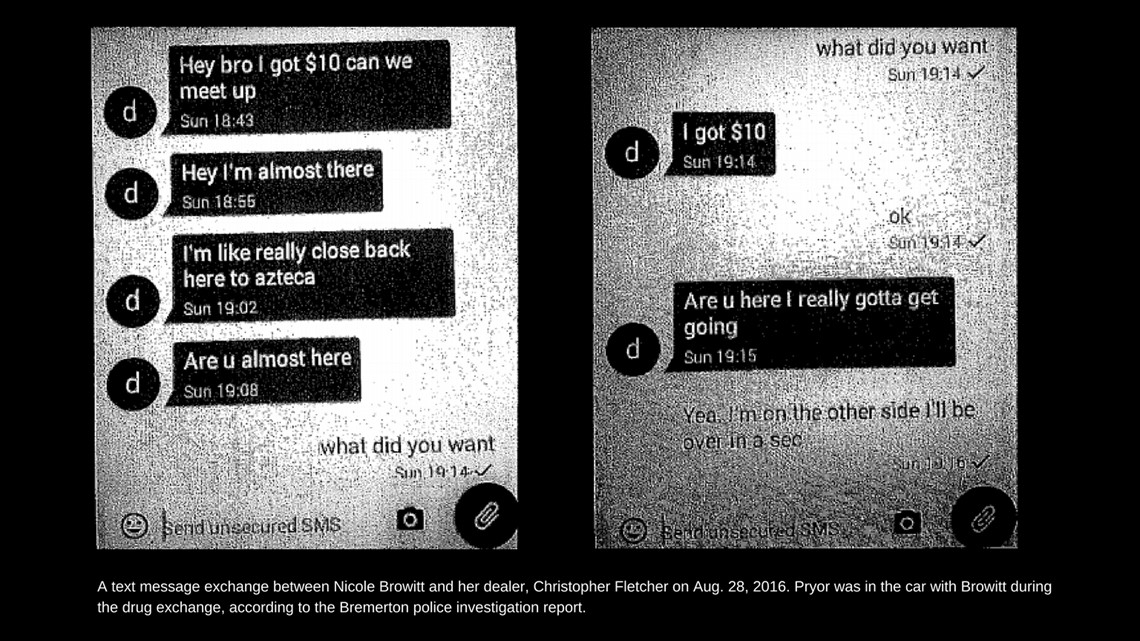

Text message conversations between drug users and their dealers often play a key role in controlled substance homicide investigations, Greenhill said. It helps detectives create a timeline between a drug deal and a drug overdose death.

"If somebody died within an hour of (a dealer) delivering the drug, there's a good chance we can prove who the dealer was," Greenhill said.

In Tylar Pryor's case, text messages and witness statements helped investigators confirm who sold heroin to Browitt, the woman police arrested after Tylar's death. It was the same batch Tylar used for the first time that August night.

The Blurred Line Between Dealers And Users

Some officials like Kiessling, the Pennsylvania county coroner, take a firm stance that drug dealers are murderers, but others argue that a dealer is not to blame for a person's death.

Those people say that drug overdose victims made a choice to take the drugs that killed them, in most cases. They say drug dealers are often addicts, too.

In several local cases, the people charged with controlled substance homicide were the victims' friends and relatives.

"Tomorrow I can bring you drugs, and the day after, you could bring them to me. The relationship between users and dealers is (not always clear). This isn't the Mexican Cartel coming in to sell drugs to people on the streets," said Larson, King County's chief criminal prosecutor.

'Going After Dealers is Like Whack-A-Mole'

There's not a consensus in the law enforcement community on whether charging dealers in overdose deaths has a significant impact on solving the nation's opiate crisis.

Some believe it's a way to reduce the supply of drugs coming into communities, but a drug trafficking expert said he doesn't think it's an effective strategy for large urban communities, like in the Seattle metropolitan area.

"Frankly, going after dealers is kind of like whack-a-mole to be honest with you. You knock one down and two more pop up down at the corner down the street," said Steven Freng, prevention and treatment manager at the Northwest High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area. "The entire issue has more to do with the availability and accessibility of heroin than any individual dealer."

But Greenhill said prosecuting dealers chips away at the larger problem. He believes the threat of being charged for a death is affecting dealers because he's seen their reactions firsthand.

"I've seen more emotions from them versus if we were to say 'Hey you are under arrest for (a) delivery (charge).' It hits home more knowing that they are going to be accountable for someone's death. I can see it impact them," Greenhill said.

In Tylar's death investigation report, Greenhill wrote that Fletcher, the male dealer police arrested, was visibly upset when he told him Pryor was hospitalized from the heroin he delivered to Browitt in the East Bremerton grocery store parking lot.

"I noticed Christopher had a somber look on his face when I said this, and he began to explain how he 'does not want this anymore,' and continued to tell me that he wanted to be clean and wants to get help," the detective wrote in the Aug. 31 report. "Christopher had tears running down his face and appeared to be sincere in his words.

'I Don't Want To Call The Cops Because I Might Go To Jail'

Critics of prosecuting dealers for homicide said the tactic is dangerous because they believe it discourages people from calling for help when they witness an overdose. Many drug overdose fatalities occur because peers delay or forgo calling 911 out of fear, according to experts.

"(They would say,) 'Oh my god. Someone just overdosed. I don't want to call the cops because I might go to jail,'" said Sgt. Sean Whitcomb, public information officer at the Seattle Police Department, as he described why the department doesn't pursue controlled substance homicide investigations.

In Washington, people who seek medical assistance for someone who has overdosed on drugs can't be charged or prosecuted for possessing a controlled substance. But the statute does not reference protection from a controlled substance homicide charge.

"On one hand, we don't want to dissuade people from calling us in emergencies for fear of being charged with a homicide," Renfro said. "But it's a tough battle for us to fight right now. We need to let people know that if you deal a poison to somebody and they die, you'll be charged."

'Let's Try Not To Use Jails And Prisons'

Schnepf, the Kitsap County prosecutor who worked with Greenhill after Tylar's death, said she expects to see more controlled substance homicide charges across the state unless the heroin crisis eases.

"But I think it's going to take a certain amount of training with the prosecutor's office and the law enforcement agencies to determine if that county wants to make it a priority," she said.

Larson said public officials in King County, are putting their resources toward public health initiatives that reduce harm for drug addicts, like the proposed safe-injection sites, instead of putting people in jail.

"The emerging trend is really more about let's try not to use jails and prisons to deal with drug users and drug abusers. Let's try to find more ways to use public health to reduce harm to the users and to the public to make our communities safer," he said.

Larson, the chief criminal prosecutor in King County, is a member of the county's Heroin and Prescription Opiate Addiction Task Force, which convened just more than a year ago. The 41-member group includes public officials, researchers, medical providers, first responders and policy advocates. In September, they released a 99-page report with recommendations to improve prevention and treatment for heroin and opiate addicted users.

Larson said he would still consider evidence in controlled substance homicide cases, but he said few of these cases have landed on his desk.

Whitcomb said the department's officers do not criminally investigate drug overdose deaths unless they believe someone deliberately killed another person.

"Heroin overdosing is not a police issue. It's a social issue," he said.

In Bremerton, Renfro said that investigating overdose deaths and arresting dealers is saving lives.

"I think it's just one little prong to this battle. It's not a hundred percent the solution, but a lot of these dealers are addicts themselves and by arresting them, we are getting them into treatment. It's helping to save them, and at the very least, maybe we save a life." Renfro said.

Pryor's Death Investigation Changes Course

In his final diagnosis, the doctor who treated Tylar Pryor at the Bremerton hospital last summer said she died of a heroin overdose, cardiac arrest and alcohol intoxication.

But after a lab tested the woman's blood in November, a Kitsap County medical examiner couldn't determine if the heroin killed her.

The coroner ruled the manner of death "undetermined," and that meant Fletcher and Browitt's controlled substance homicide charges wouldn't stick.

"They were home free," Martina Moreno said. "I was flabbergasted."

The two pled guilty to significantly lesser charges for delivering the drugs to Pryor, and each is serving time in prison.

For Tylar's grieving mother, Martina, losing her daughter feels like a prison sentence, too.

"That saying that a little bit of me went with you when you died? It's true. I died," Martina said.

Taylor Mirfendereski is a journalist at KING 5. Follow her on Twitter @taylormirf and "like" her on Facebook to view her stories.