Two days after the February shooting that killed 17 people at a Parkland, Florida, high school, a student did something that brought police to Seattle’s Garfield High School.

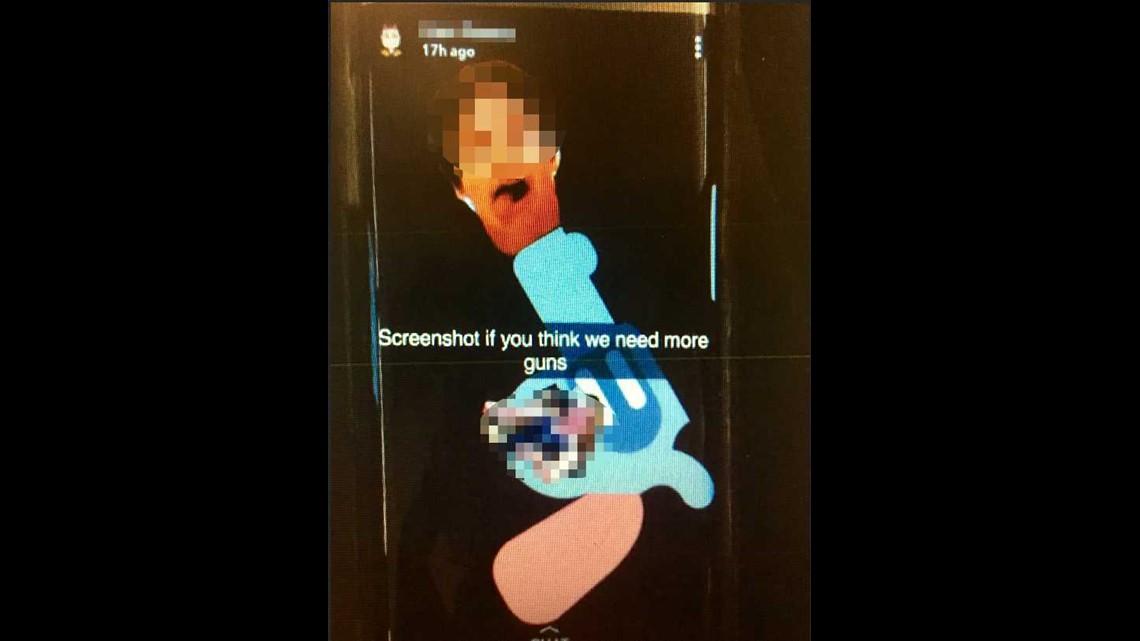

The student, a senior, posted a Snapchat image of another Garfield student’s head at the barrel of a cartoon gun. The caption read, “Screenshot if you think we need more guns.”

The police, the Seattle school district, and the student victim’s family took the threat seriously.

That led to a first-of-its-kind legal case in King County, where authorities attempted to remove all firearms from the household where the 17-year-old accused student lives.

“In 70 percent of all school shootings, the children got the firearms from their parents,” said Chris Anderson with the Seattle City Attorney’s Office.

Anderson is part of the new Regional Firearms Enforcement Unit that strives to prevent gun crimes, typically those involving domestic violence or extreme risk protection orders.

Trying to stop the next school shooting is also part of the unit’s mission.

“It’s a whole, new groundbreaking field. It’s a whole, new body of work,” Anderson said.

Prosecutors on the firearms enforcement unit advised the victim’s family that they could file an anti-harassment order against the accused student, and request a court order requiring that the student live in a household where no firearms are present.

“If you do not remove the firearms from the father, you do not really remove the access to the firearms for the child,” the victim’s father told a judge in a King County courtroom.

KING 5 is not naming any of the parties involved since both the accused and the victim are juveniles

On March 6, a King County judge issued a civil “weapons surrender” order requiring “any household members who own or possess any firearms” to turn their guns over to police for safekeeping.

The teen’s father reluctantly gave to police the three firearms he owns – a Taurus handgun, a shotgun and a rifle.

In addition to the offending Snapchat image, a judge found the 17-year-old student talked about pulling a fire alarm and shooting students, and about shopping for guns on Craigslist.

The teen’s attorney argued that the Snapchat post and the other comments were in jest, and said the students who heard them did not feel threatened.

Prosecutors initially charged the teen with felony harassment in King County juvenile court, in addition to the civil anti-harassment order filed by the victim’s family.

Anderson says this legal tactic has now been used in a half dozen cases of school threats in Seattle and King County, involving college and high school students. In all cases, household members of the accused willingly handed over their firearms as the case was resolved – all except one.

The father in the Snapchat case hired an attorney to argue that the weapons surrender order violated his 2nd Amendment rights. In a legal brief filed in May, the attorney said the man’s son was the party facing the criminal harassment charge, and that “the Court has no statutory authority to order a nonparty to surrender weapons.”

After hearing arguments, Judge Susan Amini agreed.

“The court has no jurisdiction to tell him what to do,” the judge said of the father’s refusal to voluntarily hand over his guns.

The order required Seattle police to return the father’s firearms, although the man’s attorney said he has always been willing to keep them locked up at a location separate from his residence.

In the Snapchat threat case, one judge determined the weapons surrender was valid, another did not. Attorneys working for the King County Prosecutor’s Office are taking these disparate rulings in stride as they try to forge new laws and policies intended to stop school shootings before they happen.

“We can’t wait like we used to until something bad happens. We have to do something now,” Anderson said.

In late June, King County juvenile court prosecutors dropped the harassment charge against the 17-year-old who made the Snapchat threat. The civil anti-harassment order filed against him by the family of the victim remains in effect.