Whistleblowers: Army ignoring advice of medical experts

Health care professionals at Madigan Army Medical Center say soldiers recovering from combat trauma are seen as troublemakers instead of soldiers in need of help.

'The Soldiers Need Help'

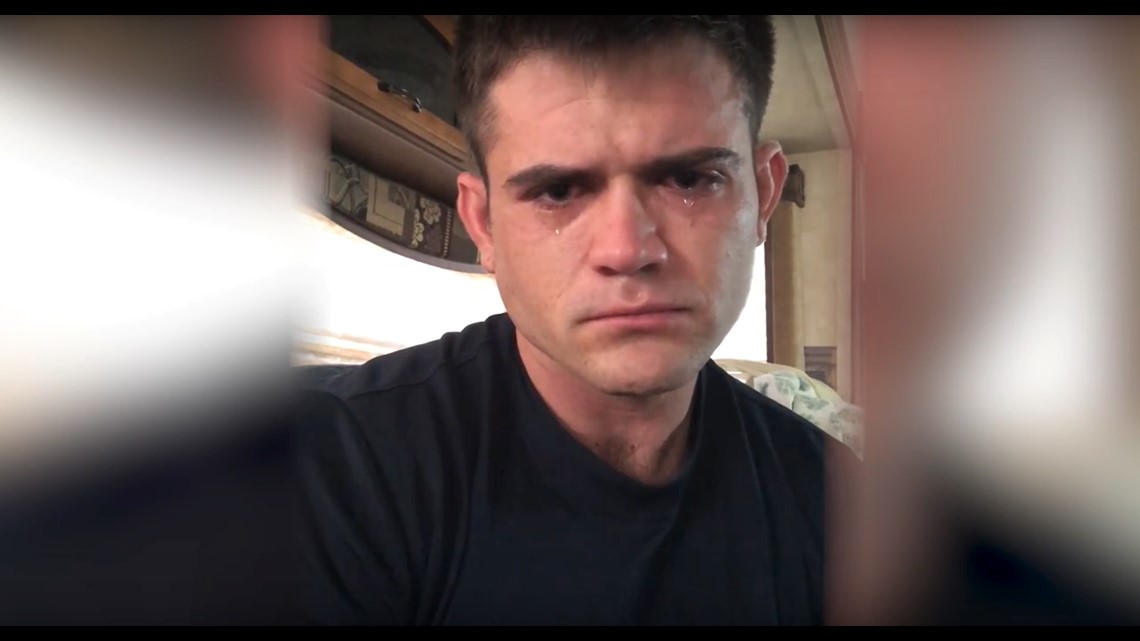

SHELTON, Wash. — A young Army staff sergeant’s face showed visible anguish as he sat inside his Shelton trailer to record a cell phone video to send to his wife.

“I lost a lot,” Kord Ball said, as tears flowed down his cheeks.“…and I don’t know how. I don’t know how. There’s no way how to change it.”

That late August 2018 morning was yet another low point for the 27-year-old veteran, who had tried to kill himself four times before. He suffers from mental illnesses, including anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder — brought on by combat-related trauma.

But despite his pleas, help wasn’t around the corner.

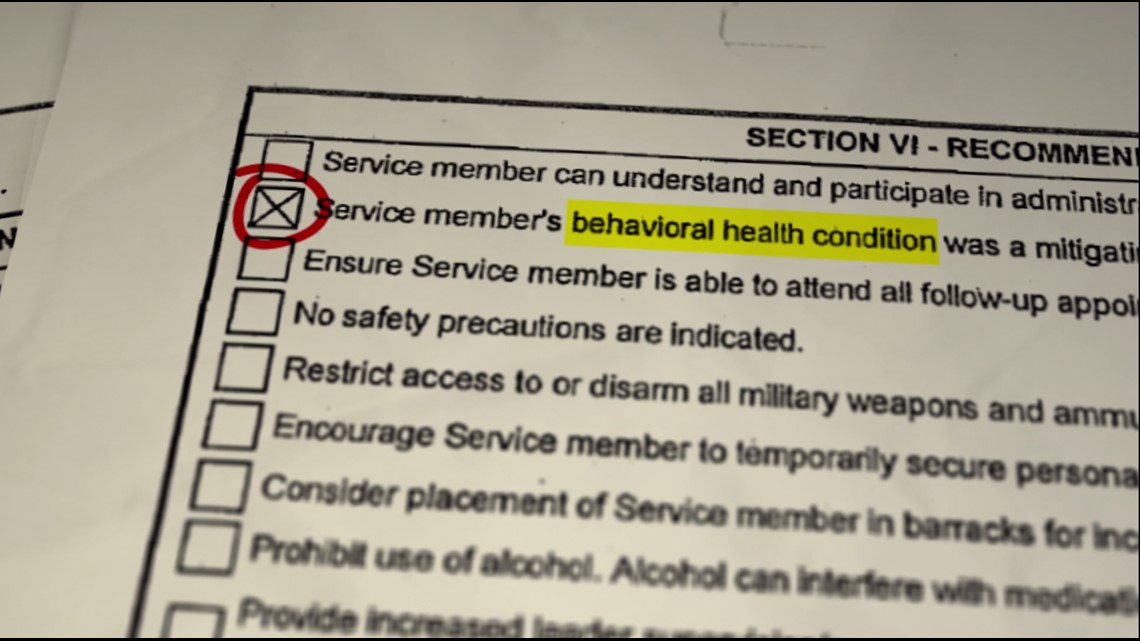

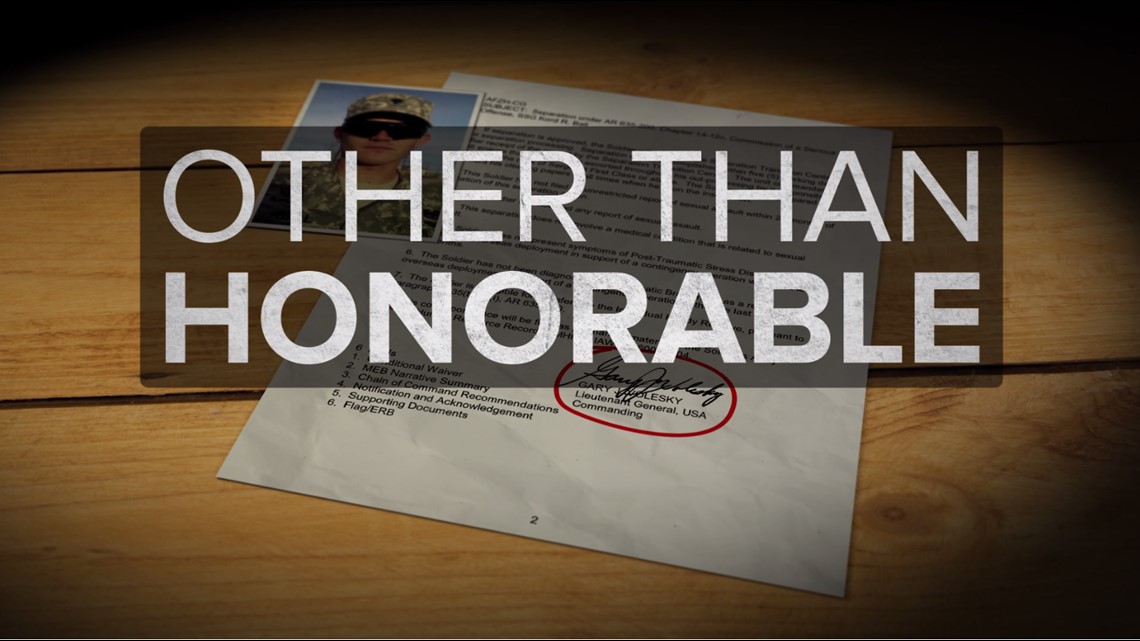

Army leaders at Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM) were just weeks away from officially kicking the soldier out of the military under other-than-honorable conditions for failing a drug test for marijuana — even though Ball’s military doctors warned his commanders that his medical conditions caused him to break the rules. That discharge status cost him the right to access long-term health care benefits from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

"They treated him as a bad soldier instead of a sick soldier," said Heather Straub, a Tacoma-based attorney who represented Ball in his unsuccessful attempt to fight the Army's decision.

Between January 2009 and October 2015, the Army separated more than 22,000 soldiers for misconduct after they came back from Iraq or Afghanistan and were diagnosed with a mental health condition or a traumatic brain injury, according to Department of Defense data obtained in 2016. As a result, many of the dismissed soldiers did not receive health care benefits that soldiers are eligible to receive with an honorable discharge.

It’s not immediately possible to quantify the number of soldiers, like Ball, who are currently affected by this problem. The Army is not continuing to track the information it previously provided, according to a 2018 Freedom of Information Act response.

But what happened to the 27-year-old is a pattern at Ft. Lewis, according to two Madigan Army Medical Center employees who have direct contact with hundreds of JBLM soldiers who have mental health diagnoses.

KING 5 agreed not to identify the employees. One is a program administrator and the other is a Madigan psychologist. They fear retaliation because they do not have permission from the Army to talk to the media.

“The soldiers need help. The American people do not know what’s going on. If I was not around these soldiers, I wouldn’t know. Sometimes I sit and I’m just amazed at how bad these soldiers are treated,” the Madigan program administrator said. “It’s like the rats jumping out of the water. ‘Hurry up and get them out. They’re too much trouble.’"

The employees said it’s common for Army commanders to view soldiers with service-related behavioral health conditions as defiant troublemakers who need to go — because the "acting out” symptoms of their medical conditions can seem like personality flaws to military leaders who don’t understand their illnesses.

“I think a lot of commanders feel they have to set an example — that if they don’t punish a soldier, then it’s not sending the correct message to other soldiers,” the program administrator said. "They only see the misconduct and they really firmly believe that the soldier uses the behavioral health condition as a pawn. I've had commanders say that."

There are safeguards in place to prevent that from happening. Army soldiers who are involuntarily separated from active duty must first receive a separation health assessment to determine whether their medical conditions played a role in the alleged misconduct. But the Army’s longstanding medical review process and policies to protect those sick soldiers are often not effective, the Madigan employees said, because commanders have the power to overrule the medical experts — and they frequently do.

“There is widespread frustration (within Madigan) right now because the perception is our recommendations seem to be ignored,” the psychologist said. "Some soldiers with proven medical dysfunctions are being kicked to the curb and dehumanized….(They’re) the victims of an injustice by a system that’s really way bigger than they are.”

A Madigan program director— not interviewed for this story — also recognized the pattern while testifying in support of Ball at his military separation hearing.

“I feel very strongly about this situation for [Staff Sergeant] Ball and soldiers in general,” Michelle Hooker, clinic director of the Army Substance Abuse Disorder Clinical Care program at Madigan, told members of Ball’s separation board. "This seems to be common in JBLM, depending on the unit and commander.”

Col. Lee Peters, an Army spokesman at JBLM, declined an interview request and did not answer specific written questions about the Madigan employees’ claims or the broader issue. He also did not respond to questions about how Ft. Lewis leaders hold commanders accountable for making the right decisions in separation cases where service-related mental illnesses play a role.

In a statement, Peters said that thorough medical reviews are a routine part of the separation process. He said commanders review each case individually in detail using a "holistic" approach that considers all available information about a soldier, including a soldier's medical history, input from subordinate commanders, medical professionals and subject-matter experts.

"All the while, the commander requires the Soldier to maintain discipline, standards and conduct expected a soldier," he wrote. "We comply with all Army policies relating to Soldier separations, and are confident this process is fair, objective and deliberate to ensure our Soldier's health and well-being are always considered."

'She Was Not Going To Give Him A Freebie'

In Ball’s case, the soldier racked up a long list of offenses in the heart of his struggle with mental illnesses.

Military doctors had already declared him unfit for duty because of his anxiety and PTSD. But as he waited for the Army to separate him from the service for medical reasons, he got in trouble for disrespecting his commander, missing doctor’s appointments and mandatory morning check-ins on base. He went AWOL for seven days, and he failed a drug test for marijuana while he was self-enrolled in the Army’s substance abuse treatment program.

Records show Ball’s commanders viewed his actions as deliberate. He “knowingly and willfully used illegal substances,” his captain wrote in his separation paperwork. She added that his behavior and drug use is a “poor reflection” on the Army. Another commander wrote that he “consciously elected to violate soldier standards.”

Even though his behaviors violated Army regulations, doctors say Ball's missteps, including self-medication, are textbook symptoms of certain mental health disorders, like anxiety and PTSD.

“We have an expectation that we can send people off to a war zone and have them see and do the things that they’ve seen and done, and that it’s not going to impact them,” said Dr. April Gerlock, a former VA medical provider and a PTSD expert based in Western Washington. “And if it does, that they are are deficient in some ways — that their character is deficient. They weren’t strong enough. They don’t have morals — that sort of thing. When they get in trouble, they get discarded.”

The Army’s own medical providers, including a psychiatrist and a psychologist who treated Ball, went out of their way to warn his chain of command — in person and via e-mail — that his medical conditions significantly contributed to his behavior. They said punishment put the soldier at risk of suicide, and that he’d need medical care for the rest of his life, according to a review of the Ball's separation records.

Hooker, the substance abuse program director, also testified that she begged the soldier’s captain and other commanders not to give him a discharge status that would impede his ability to access long-term medical care.

“I really believed that he was going to commit suicide. Life felt like it was over for him,” she told board members during his separation hearing. “[His commander] was very agitated with me. She basically said that she was not going to give him a freebie.”

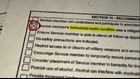

In addition to pleas of Ball's direct providers, a military psychologist conducted a routine behavioral health screening as part of the separation process. He checked the box that confirmed the soldier's mental health was a mitigating factor in his marijuana use.

A high-ranking military surgeon, who was one of the last to review Ball's case following his separation hearing, acknowledged this behavior was "correlated to his mental health." But he said it doesn't get him off the hook from his "responsibility as a soldier.” And in September 2018, JBLM’s commanding general, Gary Volesky, signed off to kick Ball out under other-than-honorable conditions.

“There’s a behavioral health condition that’s sitting right there with the arrow pointing to why the soldier did the misconduct, but yet in still, we want to hold them to the standard of a well soldier — a soldier with no behavioral health condition or problem,” the Madigan program administrator said.

“What’s the point of having the medical community weigh in and validate if it’s not going to be taken into consideration?” the official added.

'Commanders Should Not Have That Amount Of Power'

In the Army, individual commanders can halt the medical separation process in favor of pursuing disciplinary action against a soldier.

“Commanders are responsible for balancing the soldier’s circumstances, including medical history with the need to promote good order and discipline,” Lt. Col. Dennis Sarimeno, chief of the behavioral health division at the Office of the Surgeon General, wrote in an e-mail, adding that "checks and balances are in place to ensure we do the right thing for our Soldiers and the Army.”

The Army’s administrative separation process is designed to ensure that both medical providers and commanders have a chance to review and weigh in on a soldier's situation before his or her case makes its way to the commanding general’s desk for a final decision.

The commanding general at each Army installation is responsible for reviewing the results of the separation health assessments and also the recommendations from a soldier’s chain of command. But regardless of recommendations from the experts, he or she has the power to make the final call about a soldier’s future in the military.

“The commanders should not have that that amount of power — not when there’s a medical condition not the table,” the Madigan program administrator said.

The Madigan psychologist and the program administrator said they think the Army should change it’s system so commanders are required to follow recommendations from a soldiers' direct medical providers.

Army officials did not respond to questions about whether they will consider changing the existing process.

'It's Probably Going To Get A Lot Worse'

Veterans with an other-than-honorable discharge do not typically qualify for veterans benefits, even though many suffer from service-related trauma.

They are eligible to receive short-term medical care from the VA, but in order to receive long-term health care, they must apply for special consideration. The process can take months and sometimes more than a year.

Medical experts, like Dr. Gerlock, say the process of fighting for long-term health care can be overwhelming for soldiers, like Ball, who suffer complex mental health conditions.

"It gives us something to think about. If a person has untreated complex problems like these, it's not going to get better for them when they get out. It's probably going to get a lot worse," Gerlock said.

Ball, who moved to New Hampshire in October to be closer to his family, said his mental health conditions have not improved since he left the service. He said he's waiting on the VA to make a decision about his health care.

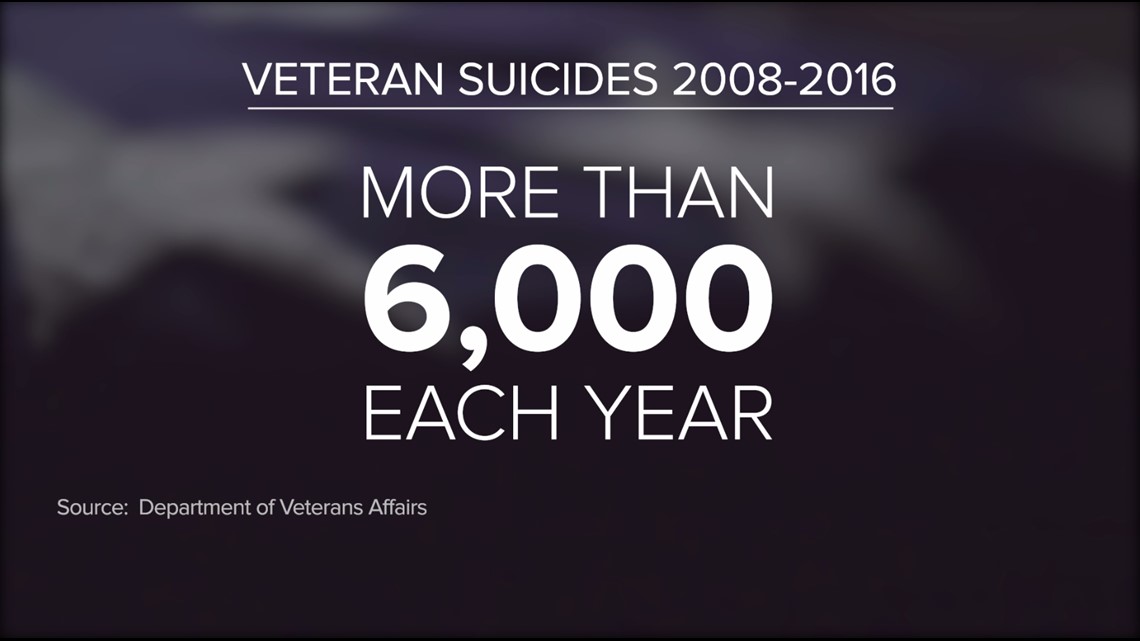

"There are a lot of other Sgt. Ball's out there – a lot – that we don't know about. Probably some that have had it even worse, and its sad," the Madigan program administrator said. "I think this is why we continue to lose our veterans."

Between 2008 and 2016, more than 55,600 veterans killed themselves, according to the VA's latest national suicide data report, published in September.

"Until we stop the madness and help our soldiers and get them back on track, this is just going to continue to happen," the program administrator said."Our soldiers are broke....We don't allow them to heal."